A World Shaped by Magic

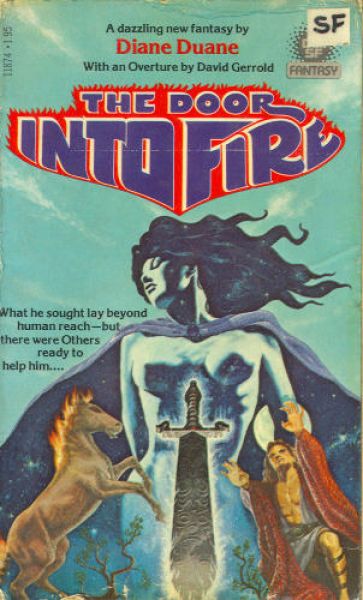

The Door into Fire (The Tale of the Five, volume 1)

By Diane Duane

2 Apr, 2016

0 comments

1979's The Door into Fire is the first volume of Diane Duane's Tale of the Five. As I recall, there were to be at least four books in the series, but as of this posting, only two further volumes, The Door into Shadow and The Door into Sunset, have been published. A fourth book, The Door into Starlight, is mentioned on ISFDB, but only as “unpublished.”

In a world where grimdark rules the fantasy bookshelves, this book may seem like an oddly touchy-feely secondary world fantasy. It was even more remarkable back in the Disco Era, when it was first published.

The Middle Kingdoms are a land shaped by magic, a shaping that goes back to the dawn of history. As you know, Bob and Bobette, magic always has a price. The Middle Kingdom variety of magic that draws on the Blue Fire has the heaviest price of all: its practitioners, nearly always women, die before they are thirty. The reasons why this is so are unclear; but the reality is undeniable: to embrace the Blue Fire is to embrace mortality.

Herewiss, the first man in centuries to draw on the Blue Fire, knows and accepts its price. His problem is that although he has a respectable skill with more mundane forms of magic, something prevents him from fully mastering the highest form. Years of experimentation have produced only failure, a failure unique (so far as he knows) to him.

That is not the only problem Herewiss faces.

1) The great love of his life, Prince Freelorn, has an unfortunate taste for adventure. Freelorn is also on the losing side of a dynastic struggle.

2) Herewiss enjoys poking into archaeological sites filled with Things Man is Better Off Not Knowing.

3) He has formed a magical partnership with Sunspark, a fire elemental who is one part WMD to one part capricious whimsy.

But the greatest challenge Herewiss faces is the one he would most like to avoid confronting, the aftermath of a mishap that ended with his own brother dead on Herewiss' own sword. As this is a world where the dead are not necessarily gone from one’s life, there is a problem

~oOo~

A note about the cover: I am not entirely certain who the woman is. It could be a woman named Segnbora (a minor character in this book but protagonist of the next, if I recall correctly) but I think it's more likely to be this world's creation goddess.

Some people build worlds by accretion: they come up with a few basic rules and follow the implications for worldbuilding. Others, and I think Duane is among them, take stock settings and then add new details to taste. The problem with the second approach is the result may not make a lot of sense. It's the same issue I had with de Bodard's Paris books1: adding magic fundamentally changes the world, so why would the result look anything like ours? Duane's world is basically a medieval European world that also happens to have real, functioning magic, magical beasts (some of whom are malign and some merely dangerous); accessible gods rather than one distant, omnipotent deity, and wandering scholars any one of whom could become a weapon of mass destruction. If you’re going to enjoy this book, you have to ignore the fact that this makes no damn sense. Fortunately, making that kind of sense was not the point.

What made people notice this book back in 1979 wasn't the rather conventional secondary world, but the romantic and (tastefully soft focus) sexual elements. This is a world where petty details like gender or race or one person being composed entirely of combustible materials while their lover is an ever-burning being of smokeless flame are no impediment to romance or sex2. In these modern days, a novel about a young man riding off to save his boyfriend would not warrant a raised eyebrow, but 1979 was only a decade after Stonewall. While Canada might have modernized its laws, Duane's native America was hopelessly barbaric somewhat slower to follow Canada's example.

I should add that the characters are also in no way wedded to the idea of couples as the default arrangement, or to obsessive monogamy. And while the running theme may be inclusive, that does not keep the characters from having some pretty brutal arguments. This is a nice universe but not a perfect one.

Some of the relationship worldbuilding was drawing on the zeitgeist of the 1970s, but not all of it. It should be noted that 70s open-mindedness was not universal; it was an alternative lifestyle, not the norm. Of course, I come from notoriously cosmopolitan Waterloo County, so all this stuff was no shock to me, but ... I suspect that there are a lot of people out there for whom this book was an enormous eye-opener, their first introduction to the idea that that maybe the standard models of courtship and marriage, as presented by CBS, ABC, and NBC, might have ignored some very interesting possibilities. I would guess that those people passionately loved this book, and still remember it fondly.

You might too. Which why I am pleased to say the trilogy is in print and available here.

1: Another example: the city and castle walls in D&D make no sense in the context of wizards and fell beasts who can easily circumvent aforesaid walls. But the walls are there because D&D is drawing on Dark Ages lore.

2: It was only by an act of pure will I did not call this review "a hunk of burning love."