Discontentment in utopia

Don’t Bite The Sun (Biting The Sun, volume 1)

By Tanith Lee

5 Oct, 2014

Because My Tears Are Delicious To You

0 comments

1976’s Don’t Bite the Sun is apparently the first volume in a trilogy but while the second book, Drinking Sapphire Wine, saw print in 1977, the third volume was never published. I only just discovered there was even supposed to be a third one and I have no idea what it would have been about. My copy is the first printing of the mass market paperback and I read it in a way a reader coming to it could not today, on its own and without reference to the sequel. I am going to tried hard to replicate that experience here.

The three domed cities – Four-BAA, Four-BEE, and Four-BOO — of an unnamed desert world1 shelter a quietly utopian society where all material needs are met. No person starves, no person needs to fear being homeless, gender is a matter of choice and even death itself has been vanquished. Created in more abstract ways than we are, each person can look forward to childhood, an intensive education they will not remember and will never put to use, an extended period as a “Jang”, enjoying all the hedonistic pleasures on offer, followed by a sedate adulthood and finally willful amnesia and recapitulation of the child-Jang-adult cycle. Eternity stretches before each person, as endless, mutable and essentially changeless as the deserts themselves2.

Unfortunately for our unnamed protagonist, that still leaves the top three tiers of Maslow’s hierarchy — love and belonging, self-esteem and self-actualization – and while those around them have those needs met to the satisfaction of the quasi-robots who run this society, the narrator is crippled by a lamentably growing consciousness that their life is essentially shallow and in that context unrewarding.

Like a young person of our time – well, of my time. Young people today have nothing to look forward to save slaving tirelessly for plutocrats, inescapable poverty and the inevitable organ harvesting amid lectures on how terrible they all are – the narrator searches for something meaningful to do with their life. Each exploration ends in abject failure as the narrator comes face to face with the fact that the quasi-robots do such a good job of running things that there is nothing but hedonism and pointless make-work to look forward to. Art has been reduced to paint-by-numbers and the jobs the adults are allowed to take upon themselves are totally irrelevant to the functioning of the cities because of course no sensible quasi-robot would leave anything important to mere fallible humans the quasi-robots understand so very well. Even Jang acts of rebelliousness are taken into account and carefully neutralized of all consequence before they even happen.

All this is underlined when an archaeological expedition into the desert reveals that there is no escape from the coddling quasi-robots. This turns out not to be entirely true; while the narrator will return to their home, misadventure and unexpected biophilia gives a glimpse of something grander than their little snow-globe community, at a terrible cost: inklings of mortality and a clumsy fumbling towards empathy. The narrator takes a first step away from eternal childhood.

Lee is very hit or miss for me but the books of hers that I like I like very much, which is why I have a shelf full of her works. This is not my favourite Lee – that would be Red As Blood, which was just the right book at just the right time — but it is among my favourites. It’s so obvious why a teenager might find this has particular resonance I won’t waste time talking about that but I will say my enjoyment was unsullied by the greater perspective the subsequent decades have given me.

This is a strangely amnesiac novel, almost entirely lacking the clues to time or place other books would have: the nameless narrator lives on a desert-covered world equally nameless at a time left carefully undefined; The people of this world – or perhaps the quasi-robots who actually run it — have done a thorough job of destroying history on this world, either by allowing it to vanish under the sands or by presenting it in a manner calculated to erase any interest in it. I think this is quite deliberate, and I think it goes back to a phrase the narrator finds on a fragment of pottery out in the desert

Don’t bite the Sun, stranger. You will burn your mouth.

That’s terrible advice but the people of the three cities take it very close to heart. They reject lasting pain and deep disappointment in favour of a carefully managed world with no extremes of any kind, no lasting sorrow but also no lasting joy; history has to be cast aside because the last thing most of the people want is any kind of greater perspective. What the narrator finds most grating about their society may be its goal.

It would be easy to see the quasi-robots as a variation on Jack Williamson’s Humanoids from “With Folded Hands” but my take on this novel is that the quasi-robots were forced into the role by their creators and that bitter dissatisfaction that peeks out from time to time when the quasi-robots interact with humans is that the quasi-robots were given just the wrong amount of self-awareness and lack of free will (although perhaps they need it to do their assigned tasks). It’s the consciousness that makes the difference between a robot and a quasi-robot; for the narrator this is a flawed utopia but it’s much worse for the quasi-robots.

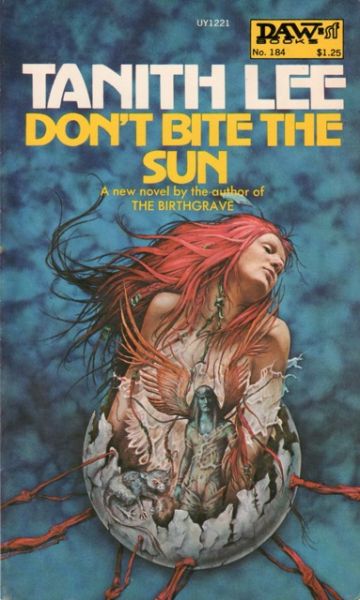

This is another book where it’s not just the book but a specific edition of it that I like. DAW published an omnibus of this and its sequel -Biting the Sun, in contrast to an earlier omnibus confusingly called Drinking Sapphire Wine — and while I would recommend buying that or any other edition you see, for me the pleasantly nostalgic brain tingles are only triggered by the version with the Brian Froud cover. I don’t know why I am so particular about editions; it should be the text alone that I like.

Jo Walton reviewed this and the sequel, contrasting and comparing them to Clarke’s Against the Fall of Night. I had not thought of the Lee and the Clarke together and it amused me that as far as internal evidence goes, they could actually be set on the same world in different periods. I think that’s convergence and not deliberate parallelism but would be happy — deeply resentfully happy — to be corrected on this point, just as I am when people thoughtfully point out all my typos.

I don’t think the omnibus is currently in print — if it is, DAW’s site managed to conceal that fact from me — but there is an ebook available, at least for people in Britain.

[Added later] I am an idiot, I was looking at the wrong publisher: Bantam Spectra published the US omnibus.

About the omnibus title: there have been at least three variant titles: Drinking Sapphire Wine (Hamlyn, 1979), Het Jang Fenomeen (Meulenhoff, 1989) and Biting the Sun (Bantam Spectra, 1999).

- The details we are given – deserts, egg-laying mammals – could fit a far future Australia. I am as horrified as you are.

- Which raises the question of how three cities can contain all the people who ever were since they conquered death? I think there are two possibilities: either this state of affairs is comparatively recent or the quasi-robots are quietly putting people into storage, possibly long-term or even eternal. Perhaps a spade to the back of the head and a quiet grave in the desert are involved.