Drafts

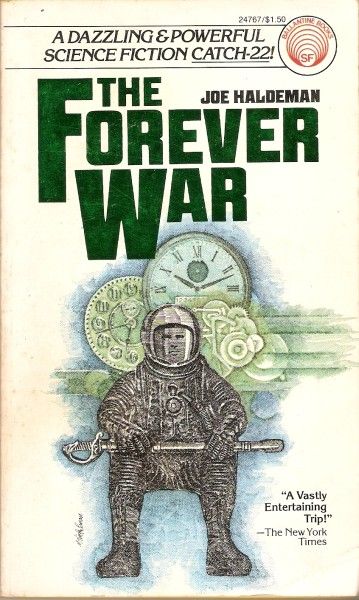

The Forever War (Forever War, volume 1)

By Joe Haldeman

6 May, 2015

Military Speculative Fiction That Doesn't Suck

0 comments

This is a case of a commission dovetailing nicely with my themed reviews. For the most part I would prefer to stick to military speculative fiction that I think readers may have overlooked. There are a few classics, generally early ones, that I believe it would be illuminating to review [1]. One of those is Joe Haldeman’s classic 1975 novel, The Forever War.

When I reread this book, I remembered a more obscure work by the same author, an early short story called “Time Piece”, which was published in 1970. I don’t know of any other review that has compared the two. This may be because “Time Piece” didn’t win the Nebula, the Hugo, the Ditmar, and place first in the Locus, which The Forever War did. Something told me that it would be interesting to compare the two works; I’m glad I did.

The edition of The Forever War I am reading is the 1976 mass market paperback, first printing. I understand there is a later, somewhat different edition; I don’t own that one. The edition of “Time Piece” I am reading is the one in Reginald Bretnor’s 1980 collection The Future at War: Orion’s Sword.

“Time Piece”• (1970)

Humans have learned to use a combination of vaguely described “relativistic discontinuities” and near-light travel to traverse the galaxy. The cost is measured in centuries; what may be months for spaceship passengers is years on Earth.

Humans encounter an extra-ordinarily fecund race, dubbed the Snails, and find themselves caught up in a war to see which of them will rule the galaxy. The war is brutal — the odds of surviving each mission is about fifty-fifty — and seemingly endless. Soldiers who, like Fred Naranja, manage to survive and find themselves displaced in time, with nothing in common with the people of the odd future in which they find themselves.

Fred and two fellow soldiers, Fred Sykes and Paul Spiegel, are sent on a scouting mission to a Snail-occupied world orbiting Antares (a world which the humans had previously overlooked, assuming (for good reason) that Antares could not possibly have an Earth-like world). The mission goes poorly and only Fred escapes to tell the tale.

What Fred can judge from his perspective as a flying Dutchman is that while the war is drawn out, it is in no sense endless, nor is its outcome in doubt. For each world the humans colonize, the Snails colonize ten.

The Forever War • (1975)

In 1980, humans discovered how to use collapsars, which we call black holes, to traverse vast distances in an instant [2]. Conveniently for the plot, the nearest known collapsar to the Sun was only six months away (at an acceleration of a mere one gee). At some point we also learned how to manipulate tachyons, allowing such applications as tachyon rockets offering arbitrarily high delta vees [3] within the confines of relativity. The entire galaxy was within our grasp.

The coin demanded by the collapsar and tachyon rocket system was time: Sol was lucky; its nearest collapsar was only about a tenth of light year away. Other promising destinations weren’t so lucky. The trip from Sol to collapsar to collapsar to destination could eat up months for passengers, which meant years and more back on Earth. This wasn’t so important for colonists, but travellers returning home would find themselves living examples of the Twin Paradox.

By 1992, it was clear we were sharing the galaxy with an alien race dubbed the Taurans. Having interpreted various events as acts of hostility on the part of the Taurans, the United Nations, by then the effective government of the entire human race, declared war on the Taurans. Only the best and the brightest would do for this war and so it was that physics student William Mandella found himself drafted to serve in a war that would span the local group and would therefore last centuries.

The novel follows Mandella through four basic stages of his career: Private Mandella, Sergeant Mandella, Lieutenant Mandella, and finally Major Mandella. (If this makes the book sound like a fix-up, that is because it is.) Each tour of duty involves longer and longer jumps through time relative to Earth’s frame of reference: 1992 – 2007, 2007 – 2024, 2024 – 2389, and finally 2389 – 3143. Each tour of duty leaves him increasingly alienated from civilian society, to the point that the people on Earth are as foreign to him as the Taurans.

It’s hard to say which is more central to the UN’s military doctrine: depraved indifference to the well-being of the elite soldiers they are using up in the Forever War or monumental clusterfucks for which only the front-line grunts ever pay the price. There is no accountability; by the time the news from the fronts filters back to high command on Earth, the people responsible for the glorious doomed plans are since long dead.

The only bright note in Mandella’s life as he fast-forwards through centuries towards whichever battlefield will prove to be his last is that he is accompanied on the way by the love of his life, Marygay Potter. And that’s not that much of a consolation. Her odds of surviving are no better than his and there’s every chance that one of them will end up hosing the other’s remains off the inside of an acceleration pod.

Assuming the Brass doesn’t decide to assign her somewhere a hundred thousand light-years and centuries away from Mandella.

~oOo~

It is obligatory to start off by mentioning that Haldeman served in the US forces in the Vietnam Conflict, a conflict in Southeast Asia which the US was totally winning until President Jane Fonda surrendered to the Commies at Munich. Or something like that. I am not a historian. There are a number of American SF authors who served in that war, authors including Haldeman (Army combat engineer), Cook (Navy), and Drake (an enlisted interrogator with the 11th Armored Cavalry). There may be French, Vietnamese, and Russian SF authors who also served but I don’t know their names. On the grand scale of things, I think it’s safe to say that Haldeman is probably towards the liberal-ish end of the Vietnam vet SF writers [4] and he appears to be distinctly unenthusiastic about war.

The Forever War is one of the books for which I retain very distinct memories of my first reading. The weather was overcast and cool; I was reading while walking up Erb from King Street [5]. There are a lot of intersections on that route and I am not entirely sure how I avoided becoming radiator art.

There’s a detail early in The Forever War that I didn’t particularly notice in the 1970s (because I was raised by wolves in a hermetically-sealed bell jar filled with Victorian-era porn and also it was the 1970s) that has quite rightly outraged a much younger reviewer (a review I will link to if anyone can remind me where to find it). Not only is “fraternization” (a weasel word for sex) encouraged in Haldeman’s imagined military, but the female soldiers are expected to have sex with anyone who wants it, on demand, even if they don’t feel like it. In one scene, the women are already exhausted and they are greatly outnumbered by the men. I think this was Haldeman’s conception of what the Sexual Revolution would look like filtered through military sensibilities (regimented, regulated, and mandatory) but in retrospect it just looks like egregiously sexist pandering.

Back in the olden days of rec.arts.sf.written, there were heated arguments about whether The Forever War has a happy ending. I lean towards “no.” While it is true that Mandella has a happier fate than the poor bastard in Haldeman’s first book, the 1972 War Year, he ends up a thousand years from his home era, surrounded by people ranging from weird to alien, relegated to a backwater world where he and people like him won’t get in the way. It’s “thank you for your service, now please go away so we never have to think about you again” writ large.

“Time Piece” was collected in Dickson’s 1975 collection Combat SF, which is where I first encountered it. Despite being published before The Forever War, I didn’t happen across Waterloo Public Library’s copy of the collection, and the story, until after I had read The Forever War. I immediately pegged the story as a first draft of the novel. Even by 1970 the rough outline of what would become The Forever War had begun to gel in Haldeman’s mind. However, the differences between the short story and the novel are striking:

- In “Time Piece”, the soldiers are volunteers. In The Forever War, they are draftees.

- The Forever War replaces relativistic discontinuities with collapsars; by the mid-1970s, black holes were as sexy as perms, platform shoes, and bell-bottom jeans!

- In “Time Piece,” it’s very clear why the war is being fought. That’s not true at all in The Forever War.

- The Snails’ relentless reproduction rate, coupled with their superior ability to find and settle new worlds, meant that in the long run the humans were doomed (and thanks to relativity, the long run is the short run for poor Fred). Although Mandella doesn’t find this out until the war ends, the humans enjoyed an overall advantage in the Forever War and might well have won it had the War not ended first.

“Time Piece” is pretty bitter and pretty cynical; The Forever War is bitterness and cynicism to the nth. There’s a point to Fred’s war. In the novel, the only reason Taurans and humans go to war is a combination of willful misunderstanding and, I suspect, desire to use a far-off war to use as a justification for the solidification of UN control over Earth and the other human worlds [6]. (There’s not much to hint that the UN is in any sense run democratically.) “Time Piece” is bleak. The Forever War is despairing.

1: For example, if I had not reviewed it already, Mote in God’s Eye would count and while I don’t care for it, Starship Troopers, also reviewed, is too influential to ignore.

2: Even when I first read this in 1976, Haldeman’s time line for the development of interstellar travel, let along colonization and war, seemed somewhat optimistic.

3: Most authors use tachyons — particles with imaginary rest mass that can only travel faster than light — to justify faster-than-light travel or FTL communication. Haldeman is, I think, an outlier in his use of rockets that emit tachyons. One of the odder outcomes of the math is that tachyon-emitting rockets can offer very high delta vees for very small expenditures of reaction mass. There’s no proof that tachyons exist, but if they did, and you could make a rocket that ejected them out the back, you’d have one of those classic accelerate-forever rockets.

And the reaction mass might even glow blue from Cherenkov radiation!

You might think that sounds indistinguishable from a perpetual motion machine of the first kind. I note that Haldeman does exploit the energy production potential of tachyons in a wide variety of ways, from constructive to destructive.

The one downside of tachyon rockets is that the math suggests universes with tachyons are only metastable. Tachyons might give you interstellar travel but only for as long as it took for some event to trigger the collapse of the false vacuum. Well, it’s all swings and roundabouts.

4: Weird how there don’t seem to be any Vietnam-conflict-era, amphetamine-crazed, torch-jockey SF writers, although later conflicts made up for that lack. Pity, because every minute a zoomie spends writing SF is a minute not spent dropping ordinance on allied troops..

5: My Waterloo loop for books began at Waterloo Public Library, then over to that place in Waterloo Town Square whose name I forget, to the Book Barn, up Erb to Scribes, to the U Waterloo bookstore.

6: Because this is told from Mandella’s point of view (AKA a grunt’s POV) and because he never gets close to joining the High Command, a lot of the strategic-level plotting remains the stuff of rumour and conjecture.