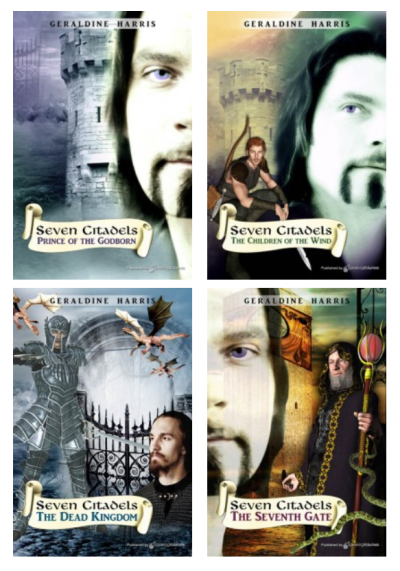

Prince of the Godborn, The Children of the Wind, The Dead Kingdom, & The Seventh Gate

Seven Citadels Quartet

By Geraldine Harris

12 Aug, 2014

0 comments

The Seven Citadels quartet is composed of the books Prince of the Godborn, The Children of the Wind, The Dead Kingdom, & The Seventh Gate and was originally published in the early 1980s.

I dithered about whether to do these as four stand-alone reviews or one but while each book works on its own, I read them all back to back and however I happen to have read something the first time is obviously the best way to have done it. Except for how I read Princess Bride, which involved having my left hand crushed under a rock; I don’t recommend that at all.

Galkis’ aristocrats can trace their lineage to gods; this is no figure of speech but while the Godborn are widely acknowledged to have gifts lesser mortals do not, it has not make the current generation better administrators or prevented them from indulging in the same sort of destructive dynastic squabbling that has crippled entirely mundane royal families. Galkis faces invasion from neighboring barbarians but appears to lack both the will and the ability to resist and a religious ceremony that goes pear-shaped very spectacularly hints that the Godborn themselves may no longer have the mandate of heaven. All seems lost.

But there may be hope in the form of a legend that says there is a Savior out in the world, trapped by seven locked gates. If someone can find the keys to the gates, they can free the Savior and so save Galkis. Prince Kerish and his half-brother Forollkin agree to leave their homeland to search the known lands for the keys and the future of their kingdom.

Of course, there are catches: Kerish is no adventurer and his temper often gets the better of him. Forollkin, of Godborn blood but never formally acknowledged by his father, has more practical skills and good deal more self-control and all things considered would probably be a lot better off if he could bring himself to run Kerish through before legging it to some distant land but alas, filial piety forbids that entirely reasonable course of action.

The other catch is that the keys are not so much lost as in the possession of seven powerful wizards whose immortality depends on possession of the keys. Physical force is unlikely to win the keys, convincing the sorcerers to embrace death by surrendering the keys willingly appears equally unlikely and since at least one of the sorcerers is the sort of cheerful fellow who decided to populate his kingdom with the walking dead, attempting and failing to persuade the sorcerer could end very badly for the princes.

Following a more or less counter-clockwise route across the map, the half-brothers and their sour but cynically faithful companion Gidjabolgo seek out the sorcerers, learning much about the varied cultures of the region en route and much about the pitfalls of great power besides. At each step failure looms and to fail one task is to fail them all.

I will admit the original art

didn’t fill me with enthusiasm and neither did the map, which is of a form familiar from dozens of fantasy novels (although perhaps not to readers as young as the target market). The collect the plot tokens aspect and the two brothers and also their sidekick struggle to overcome their personal failings as they attempt to save their kingdom from invaders also did not seem promising. All that was misleading and the author is more ambitious than is immediately apparent.

While some of the lessons learned are the standard ones, where the journey leads is not where one would expect; there is more to this world than the half-brothers knew and goals that seem clear cut become murkier as the situation becomes clearer.

The author’s purpose in acknowledging the standard tropes is to subvert most of them; for example, there is little about the actual behavior of the Godborn to suggest they are particularly gifted rulers and the examples of sorcerers themselves, some benevolent, other not, suggest that the main difference magic makes is that it enables one to make mistakes on a far greater scale than is otherwise possible; in the hands of a mage who knows what he is doing, what would normally be a tragic moment of family strife can instead be a national calamity. Power, even power coupled to arcane knowledge, is not itself necessarily ennobling and good intentions absent moderation are not necessarily helpful.

I had not heard of these books until Yoon Ha Lee pointed them out to me. They came out in the 1980s, when I was already an adult, but I can see if I’d encountered the quartet at the right age they’d have seared themselves into my frontal lobes next to the Earthsea and Heinlein juveniles. I would definitely recommend them to young readers and to adults as well.