When is a translation not a translation?

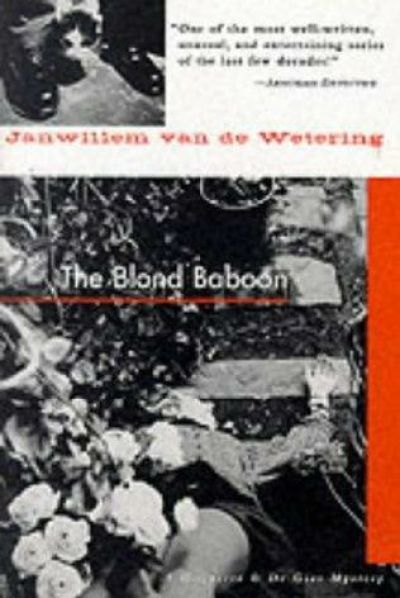

The Blond Baboon (Grijpstra and de Gier, volume 6)

By Janwillem van de Wetering

25 Feb, 2015

0 comments

Back in the 1980s, there was a very good used bookstore on King Street in Kitchener [1], a store whose name I have forgotten but whose proprietor had an uncanny skill for pointing me at mystery series she thought I would like … and buy. Janwillem van de Wetering’s Grijpstra and de Gier series was one of her recommendations. While I had read a number of police procedural series, I had never read anything like this one.

Although 1978’s The Blond Baboon is six novels (and three years) into the fourteen novel (and twenty-two years) series [2], I picked it for review because it had the unique property of being at the top of a stack of books, not trapped down where the stack would collapse if I removed it. I’ve often used this selection method and I stand by it, as do various stacks of books.

***

The novel opens with an action scene: the good-looking bachelor Detective-Sergeant de Gier and the unhappily married Detective-Adjutant Grijpstra [3] of Amsterdam’s Murder Brigade are dodging flying trees and tumbling cars. Amsterdam is being torn apart by a gale, and the government is struggling to deal with the crisis. In the middle of the chaos, the pair is called to the scene of a suspicious death. Middle-aged Elaine Carnet has tumbled down some garden stairs to her death. Inexplicably, she looks happy.

Given the weather and the fact that the stairs are outside, it might seem reasonable to conclude that Carnet was blown off her feet, a victim of the weather. However, her garden is well protected and that form of accidental death is ruled out immediately. It’s still possible she was just the victim of misadventure; after all, the steps were wet. Still, the police have to treat every unexplained death seriously, which is what de Gier, Grijpstra, their callow but well-meaning junior Cardozo, and their amiable boss the commissaris proceed to do.

What they discover is that Carnet had accumulated a fortune from her successful furniture business and that she had a past as a once-great singer. She has — or rather, had — a somewhat contentious relationship with her daughter, a string of lovers, and a business partner who may still be carrying a grudge. Carnet once tried to force him out of the furniture business to make room for her now-former lover (the blond baboon of the title). The list of people who might have had some reason to push Carnet down the stairs is not a short one; why and how Carnet came to tumble to her death are not immediately obvious.

***

I may have screwed up when I selected this for Translation Wednesday. When I was about two thirds of the way through the book, it occurred to me that I had no idea who the translator might have been. As far as I know, there’s nothing quite like ISFDB for mysteries (Stop, You’re Killing Me is handy but no nearly as useful as ISFDB), but a trip to Wikipedia yielded this ominous sentence in the entry on van de Wetering:

He usually wrote in Dutch and then in English; the two versions often differ considerably.

Is this a translation of a Dutch book (a translation done by the author) or is it an English book inspired by a previous Dutch book, both written by the same man? I don’t know.

What struck me as unusual about this series is that there isn’t the air of angry paranoia that pervades American procedurals. The cops are armed, but they make every effort not to use their guns. They worry that they might have allowed matters to spin out of control if they have to exchange gunfire with suspects. When the cops arrest people, they don’t seem particularly angry or upset with the suspects. While the commissaris has his own reason to reject a punitive approach to the law (he was a prisoner of the Nazis and that soured him on the whole sending-people-to-prison thing), the people under him also seem devoted to resolving their cases as amiably as they can.

I think we can attribute part of this humane approach to authorial experience. Having had a colourful career as a world-traveler (including a stint in a Japanese Zen monastery), van de Wetering returned to the Netherlands only to discover that he was still expected to put in the two years of public service he had skipped. When he learned that he could serve those years as a cop, he took that option.

This may be a wild speculation but … I wonder if having draftees like van de Wetering serving amongst the ranks would dilute the caste-based law enforcement systems typical of the US and Canada. In these bizarre First World countries, cops are often recruited from families with a tradition of serving in law enforcement. This seems to incline cops to view the population as divided into cops, bad guys, and civilian impediments to effective action.

Which isn’t to say that the Dutch cops in this book are entirely without flaws. One notices a certain lack of women in the police force, an absence that seems to be pronounced among criminal detectives. It is true that the police are friendly towards young women (a class that includes both the victim’s daughter and a group of prostitutes who feature in one scene), but with the notable exception of the commissaris, the police are often unkind to older women. Older women are dismissed as senile or viewed with contempt for still taking lovers. Grijpstra’s wife is vilified for being fat. (His hatred for his wife becomes bothersome very quickly. When I was first reading the whole series, years ago, long before I reached the sixth volume I was wondering why the heck the couple didn’t just divorce.)

There is also a tendency towards an ongoing genial contempt for foreigners. Nothing so pronounced as open hostility, just a dismissive attitude. Foreigners are an unreliable lot [4]; every Italian businessman who appears in the book is casually corrupt (granted, not only is that only two Italian businessmen, they are father and son). Of course, one must admit that, compared to the norms in other nations, the Dutch norms seem almost utopian. The Dutch cops may roll their eyes at foreigners, but at least they aren’t casually electrocuting them for not speaking the local language.

(The most junior Murder Squad member, Cardozo, whose exact rank seems unclear, manages to go well beyond friendly, which makes me wonder if the Murder Brigade had any guidelines regarding sleeping with suspects. I was also a little surprised that the culprit was Cardozo. This seemed more like something de Gier might do … but of course he is experienced enough that he might hesitate before jumping into bed with a Person of Interest.)

At 217 pages, this is a fairly slight novel by modern standards. The author does manage to fit in some surprising twists and turns, as well as an extensively developed red herring.

Oddly enough, although the series is named for Grijpstra and de Gier, they were not the reasons why I enjoyed and continued to read this series; the first is increasingly unpleasant and the second unmemorable. It was their elderly boss the commissaris, who stubbornly overcomes crippling pain to thoughtfully observe, contemplate and finally resolve difficult problems, who was my favorite character.

1: Back then, Kitchener had wealth of used bookstores: KW Book Exchange, The Book Nook, Now and Then, Casablanca, the bookstore whose name I have forgotten, Mike’s, A Second Look. In these degenerate modern times, we’re down to KW Book Exchange and A Second Look. I blame the interwebs, although in the case of the store whose name I have forgotten, the issue was a landlord wanting Toronto-level rents for a location in Kitchener’s ailing downtown.

2: No, I don’t want to deal with how to count The Sergeant’s Cat and Other Stories and the collection that superseded it, The Amsterdam Cops: Collected Stories. Thanks oodles, though.

3: To quote the footnote that was in every one of these novels:

The ranks of the Amsterdam municipal police are: constable, constable first class, sergeant, adjutant, inspector, chief inspector, commissaris. An adjutant is a non-commissioned officer.

4: In another novel in this series, an American tourist gets stoned before stumbling into a canal to drown. The police team resolves to make sure that tourists are better educated about how to safely consume drugs.