A Good Day to Run

By Fritz Leiber

12 Mar, 2017

Because My Tears Are Delicious To You

0 comments

To steal a description I posted on actor Amal Al’s Facebook wall a few days ago, Fritz Leiber’s 1964 The Wanderer is about “hollow planets filled with catgirls who want to steal the moon.” Many of you may think that sounds awesome or at least intriguing. Certainly a sufficient number of fans [1] thought so; the novel won a Best Novel Hugo in 1965.

The reality of the novel falls well short of its potential.

Yesterday’s Tomorrow AD: the Americans have a moon base, and the Soviets have a manned Mars expedition. The Cold War simmers, threatening to go Hot. That would be the only threat to the planet as a whole … or so they thought.

Four photographs of distorted star-fields foreshadow a grim reality. There are aliens and they are on their way to Earth. What do they have planned for us?

A garish object appears in the sky; it is visible to the naked eye. The masses, not yet told of the oncoming aliens, wonder if it might be a weather balloon. When the Earth’s moon is torn apart by the interloper’s gravity it is apparent to the meanest intellect that the Wanderer is as large as the Earth.

The Wanderer is a vast ship, able to leap between the stars. It is filled with level after level of inhabited space. In fact, the floor area within the ship is about fifteen thousand times the surface area of the Earth. There have been fictional interstellar empires whose worlds had less habitable area.

The Wanderer needs fuel, which is where our unfortunate Moon comes in. The inhabitants of the Wanderer are essentially indifferent on the crawling human vermin on the Earth. Vermin of a type observed previously, thus not interesting. A few of the Wanderer’s inhabitants do try to mitigate the effect their ship has had on the Earth but these efforts are perfunctory, sops to ease guilty consciences.

The people of Earth don’t have the luxury of ignoring the Wanderer. The Wanderer is eighty times as massive as the Moon. The tidal effects are extreme: ocean tides increase from an average of under a meter to nearly fifty meters. The Earth’s crust is strained; volcanoes erupt and earthquakes rattle the globe. It looks as if this might be the end of the world.

~oOo~

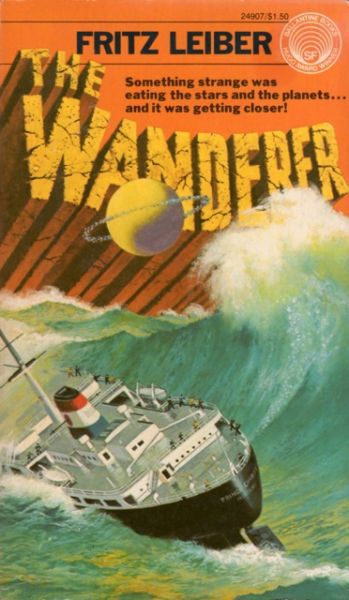

I don’t think The Wanderer has ever had a cover that rose above competent. Still, look at all those editions.

There’s a moment on page 11 of the 1976 Ballantine mass market that jumped right out at me:

(Cats) are so people. Even your great god Heinlein admits they’re second class citizens, every bit as good as aborigines or fellahin.

This is pretty typical for the book. The Wanderer is set in a future of 1964 where none of the overt bigotry that has become moderately unfashionable in our timeline has ever been questioned. While some expressions of prejudice are presented less sympathetically than others, this is a US (and presumably world) where there’s an acknowledged racial pecking order and the less sunblock you need, the farther down it you are. What the White Americans don’t suspect, until it is too late, is that there is a universal pecking order and humans are way down at the bottom of it. As below, so above.

It’s also a future in which Stonewall probably never happened, judging by the hostility one senior officer displays towards a fellow officer he (correctly) thinks may be not just a lesbian but a Lesbian. And not just a Lesbian but one who is more popular with the women on base than he is. The text supports the hypothesis that this is less because the American armed forces are a hot bed of passionate Sapphists and more because this particular male officer is a raging asshole disliked by fellow officers of any and all sexual orientations.

This book was a precursor to disaster novels like Lucifer’s Hammer. Like those later books, it takes a cast of thousands approach, showing how the Wanderer affected people across the planet. In addition to the romantic triangle of Paul, Miriam, and Don, there are New Yorkers Sally and Jake; stoners Arab, Pepe and Jake; Barbara, the elderly Grand Wizard she befriends and his black servants; soldiers Spike and Mabel; Welshmen Dai and Richard; sailor Wolf Loaner; smuggler Bagong Bung; would-be filibuster Don Guillermo; and of course the saucer fans Doc„ Beardy, Turban, Little Man and Ramrod. And the alien catgirl Tigerishka. And others not worth mentioning. Unfortunately, it’s not a particularly long novel, which means most of the characters cannot be developed in any depth.

Not only is this novel dated in ways that might distract and annoy readers, the grand spectacle that might have provided a distraction is kept largely off-stage, one epic space battle being the main exception. As words are a lot cheaper than current state-of-the-art CGI, one wonders why the author economized here.

The Wanderer is a spaceship the size of the Earth, with an intelligent population many times greater, commanding technologies we can scarcely envision [2]. Tigerishka reveals it is also a ship full of bohemians, free thinkers who refuse to be bound by the squares’ petty rules, sexy beasts who fornicate in all kinds of ways frowned on by elders. Due to lack of space and possibly the Comstock Act, Leiber largely refrains from describing this erotic free-for-all (which given the sex we do see, is just as well).

Of course, the astro-bohemians are also the sort of beings who will casually trash an inhabited planet; not out of malice but because they could not be bothered to avoid doing so. The could have dismantled one of the Solar System’s Moon-sized worlds not adjacent to the Earth. Perhaps those curmudgeonly elders have a point. The elders have, after all, converted most of the universe into useful real estate.

This is a terrible book and yet it won a Hugo. You might ask “what the helling hell, Hugo voters of 1965?” I suspect two factors were in play. First, the competition on the ballot in 1965 wasn’t particularly strong: I like Smith and Brunner, but The Planet Buyer is kind of perfunctory without the other half and The Whole Man is hardly Brunner’s best work. Davy was a serious contender but it lacked something The Wanderer has in spades, which is blatant and unabashed sucking up to SF fandom. The Wanderer is filled with references to Heinlein and Smith and science fiction in general. Voters in 1965 may be have been swayed by the fact Leiber was very clearly One of Them .

The Wanderer is available here (Amazon) and here (Chapters-Indigo).

Please direct corrections to jdnicoll at panix dot com.

1: The Worldcon voting pool was slightly smaller in the 1960s than it is today. The results were as follows:

- The Wanderer by Fritz Leiber (Ballantine Books) 52 votes.

- Davy by Edgar Pangborn (Ballantine Books) 48 votes.

- The Planet Buyer by Cordwainer Smith (Pyramid Books) 34 votes.

- The Whole Man by John Brunner (Ballantine Books) 26 votes.

- No Award 14 votes.

2: Unless you are Doc Smith or Olaf Stapledon, on whose visions of the future Leiber drew.