Back to Asimov

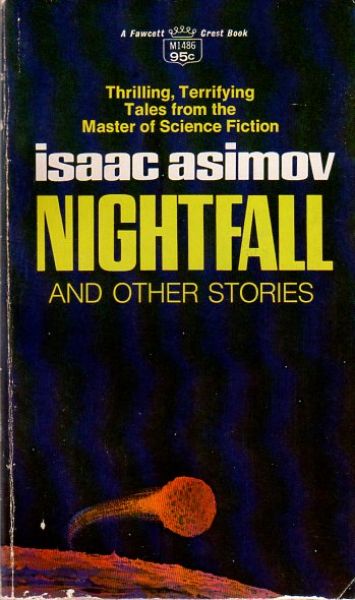

Nightfall and Other Stories

By Isaac Asimov

26 Apr, 2015

Because My Tears Are Delicious To You

0 comments

Blame my fondness for old timey radio for this review. I was re-listening to my archive of X Minus One (a 1955 – 1958 radio program featuring SF content) and was suddenly overcome by an urge to re-read this Asimov collection, an old favourite, after listening to their adaptation of Hostess.

I am not 100% sure when I first picked up my mass market paperback copy of Nightfall and Other Stories. It was published in 1970, but from fall 1970 to summer 1971, I wasn’t anywhere near an English language bookstore [1]. I must have acquired it after we returned from Brazil. I am sure I must have read it multiple times when I was a bibliophilic teen. At some point this collection ceased to enthrall — not sure when that was, but it may have been more than thirty-five years ago. It is likely that more time has passed since I last read this collection than had passed between the original publication of Nightfall (1941) and my first exposure to it in the early 1970s.

Each story is prefaced by a brief commentary from Asimov. I am inordinately fond of supplementary material like introductions and afterwords. I think I can trace that fondness to this specific collection.

Nightfall • (1941) • novelette

A group of scientists believe that they have worked out why civilization on their rather unusual planet collapses in flames every two thousand years. Alas, their preparations for the coming dark age are undermined by the fact they haven’t quite grasped the nature of the problem.

Not only was this story frequently anthologized, adapted to radio a least twice, adapted to film at least once (the exact relation of Pitch Black to Nightfall is unclear to me), subjected to an ill-conceived expansion to novel length, referenced by a number of other SF works and was featured as the 100th episode of Escape Pod. A good choice for the title story of a collection.

Asimov seems torn between being pleased that this story was such a hit and being irritated that something he wrote when he was only twenty-one overshadowed so much of what he wrote afterward.

“Green Patches” • (1950) • short story

Human explorers head home to Earth, fearing — correctly! — that they may be bringing the end of independent life with them.

I don’t know what I would do if I thought my scout ship might be carrying something a lot like the alien in “Who Goes There,” but I can be sure that “head back to and land on Earth” wouldn’t be among the options.

Hostess • (1951) • novelette

Rose Smollett, a scientist, offers her home to a visiting alien, hoping to learn more about the enigmatic races with whom humanity shares the galaxy. She learns far more than she wanted to.

At first Rose’s husband, Drake, comes across as a bit of an ass, but the more the reader gets to know him, the worse he appears.

While listening to the radio show, I noted this line: “If you are thinking of my wife, she is an example of the minority of women who are capable of making their own way in the world.” I thought this might be Asimov speaking as a sexist pig through one of his characters. After re-reading the story, I think it’s at least arguable that the author is illustrating Drake’s jerkitude and general contempt for women.

I might add that I also noticed that Rose’s friends are baffled as to why she would have settled for a non-academic, a cop, like Drake. Another interesting little social prejudice. Lots of them in this story.

This is the story Asimov tried to dictate to his wife, only to discover that when he tried composing stories out loud, the emotional parts came out as “incoherent sounds of rage.”

Breeds There a Man … ? • (1951) • novelette

A rather Fortean tale of one researcher’s struggle against the secret masters of humanity.

C‑Chute • (1951) • novelette

What would compel a rather unassuming man to undertake heroic action? A bookkeeper risks his life to regain control of a spacecraft that has been captured by enemy aliens.

I found it interesting that the aliens are not particularly monstrous. In fact, the aliens attempt to avoid causing their captives unnecessary suffering; it’s not clear the humans are as considerate.

Asimov talks about the old radio shows Dimension X and Two Thousand Plus in the introduction to C‑Chute. He comments that those shows adapted three of his stories (although he only mentions two of them, Nightfall and C‑Chute; the third was Pebble in the Sky [2]). His account is a bit misleading, perhaps due to the passage of time blurring details. As far as I know, nothing of Asimov’s ever appeared on Two Thousand Plus. C‑Chute was actually adapted by the successor to Dimension X, X Minus One (which also redid Nightfall and Hostess), not Dimension X itself.

“In a Good Cause — ” • (1951) • novelette

An activist struggles unsuccessfully to convince the independent worlds of humanity to unify against a vast, alien empire.

The aliens don’t actually seem all that unfriendly and the activist comes across as something of a wild-eyed bigot. Asimov explains that he is riffing on the conflict between the Greeks and the Persian Empire in this story. I must point out that, unlike the Persians and the Greeks, the aliens and the humans are not in competition for real estate; they are adapted to different environments.

“What If — ” • (1952) • short story

A couple is given the chance to find out what would have happened had their particular meet-cute never occurred. Was their romance inevitable or was it the outcome of a specific and unlikely sequence of events?

This seems like an exceptionally trivial application of an interesting technology, on a par with using computing power superior to that used in the Moon Program to hurl simulated birds at simulated pigs.

“Sally” • (1953) • short story

A criminal has designs on the robotic brains of a fleet of antiquated automated cars. He spends a bit too much time trying to force the fleet’s caretaker to surrender his automobiles and too little time worrying about how far the crook can push what is an autonomous metal being massing a ton or more.

“Flies” • (1953) • short story

A researcher discovers the terrible truth behind a friend’s affliction. On reflection, he declines to share what he learned.

“Nobody Here But — ” • (1953) • short story

Having created an artificial intelligence, researchers belatedly realize that they forgot to work out a way to keep the AI from conquering the world.

There’s no actual evidence that the AI is hostile to humans and strong evidence that it’s actually benevolent. This is not the only story in this collection that turns on an odd mismatch between what’s going on and how people react to it. Of course, as Asimov points out, his protagonist isn’t exactly bright.

It’s Such a Beautiful Day • (1955) • novelette

A single mother struggles to deal with her son’s unspeakable perversion: walking around outdoors!

Of course, these days she would have good reason to worry, because unmonitored rambling can earn parents a visit from Child Protective Services.

“Strikebreaker” • (1957) • short story

A visitor to an inhabited planetoid takes it upon himself to intervene in the conflict between the planetoid’s society as a whole and a despised minority. The visitor is suitably rewarded for his efforts.

I would wonder if Asimov was inspired by Letter from a Birmingham Jail, especially the bit that goes

I must make two honest confessions to you, my Christian and Jewish brothers. First, I must confess that over the past few years I have been gravely disappointed with the white moderate. I have almost reached the regrettable conclusion that the Negro’s great stumbling block in his stride toward freedom is not the White Citizen’s Counciler or the Ku Klux Klanner, but the white moderate, who is more devoted to “order” than to justice; who prefers a negative peace which is the absence of tension to a positive peace which is the presence of justice; who constantly says: “I agree with you in the goal you seek, but I cannot agree with your methods of direct action”; who paternalistically believes he can set the timetable for another man’s freedom; who lives by a mythical concept of time and who constantly advises the Negro to wait for a “more convenient season.” Shallow understanding from people of good will is more frustrating than absolute misunderstanding from people of ill will. Lukewarm acceptance is much more bewildering than outright rejection.

But … this story predates Letter. And despite the ending, I am not at all sure that Asimov isn’t exactly the sort of moderate King complains about in his letter

“Insert Knob A in Hole B” • (1957) • short story

Astronauts eagerly await the arrival of the putting-stuff-together robot, little suspecting they are in a short, comedic story.

“The Up-to-Date Sorcerer” • (1958) • short story

A love potion causes no end of havoc until someone belatedly realizes that the cure for this induced love is marriage itself.

I am astonished that Asimov managed to avoid divorce for another fourteen years after writing this.

“Unto the Fourth Generation” • (1959) • short story

The child of immigrants reconnects with his roots in an unexpected way.

Often reading one story leaves me wanting to re-read a related one. In this case, Asimov’s introduction, and its tribute to Anthony Boucher, makes me wonder if I own a copy of The Compleat Boucher.

“What Is This Thing Called Love?” • (1961) • short story

Aliens struggle to grasp the minutia of human reproduction, much as I struggled to get through this tired weezer.

Anyone know which unnamed magazine was publishing spicy SF stories in 1938 and 1939?

“The Machine That Won the War” • (1961) • short story

When national survival depends on a supercomputer operating flawlessly, how is one to deal with mounting evidence that the computer is unreliable?

“My Son, the Physicist” • (1962) • short story

Sometimes it takes a complete outsider to see the obvious way around a communications barrier.

“Eyes Do More Than See” • (1965) • short story

Entities ancient beyond human comprehension get a glimpse of what they abandoned when they embraced immortality.

Hostility to extended life runs through Asimov’s fiction. I’m not clear what it was about the idea that so affronted Asimov.

“Segregationist” • (1967) • short story

A prominent surgeon fulminates against the practice of blurring the lines between the two principle kinds of people. The big twist is that he isn’t one kind of person but the other sort.

Huh. Asimov tells us the minutiae of this story’s publication but nothing about what he was thinking when he wrote this.

~oOo~

I don’t regret re-reading this collection (although I do regret doing it in one go). These stories were showing their age when I first read them decades ago; they have not gotten any younger. However, I do think that I’ve proved to my own satisfaction that I am not unreasonably prejudiced against older SF; I have considerable toleration, even fondness, for older works.

Asimov’s prose is never more than functional, which he would himself admit, but here and there are ideas worthy considering at further length. Although perhaps not the ones Asimov intended when he wrote these stories.

1: Because it took months for our school books to arrive and because it didn’t occur to any of us to see if the University of Florianópolis had books in English until 1971, we went months without anything to read. MONTHS. My older brother recited Orphans of the Sky from memory to amuse us all. If I had had Nightfall with me, it would have been read to fragments.

Thank goodness for our shortwave and the BBC radio service.

2: This would be the utterly bizarre adaptation of Pebble that removed the protagonist to focus on two supporting characters.