Cry Havoc!

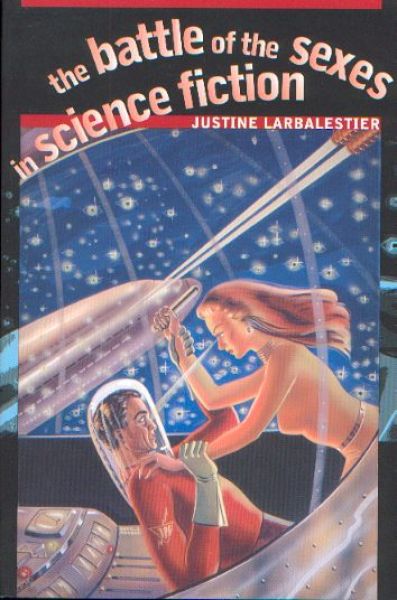

The Battle of the Sexes in Science Fiction

By Justine Larbalestier

15 Jun, 2015

0 comments

Australia is geographically isolated from the Americas and the western marches of the Old World; a certain level of cultural isolation results. This can sometimes be an asset. In the case of The Battle of the Sexes in Science Fiction, comparative isolation from the transatlantic mainstream allows author Justine Larbalestier (someone who in the early 1990s when she began the research that became this book had heard of but not read figures like Heinlein and Asimov) to take an outsider’s perspective in her 2002 study, The Battle Between the Sexes in Science Fiction.

One thing I will say up front: Eric Leif Daven was very lucky I read this after his book and not before. On its own, his book was flawed. Next to the Larbalestier, it’s crap.

List of Illustrations

Most but not all of these are reproductions of letters whose text is provided in the main body of the work. This allows the reader to see if Larbalestier has committed creative editing in her discussion of those letters, which she has not.

Comments

People with lousy eyesight may want to skip the photostats of the letters; they’re not easy to read, at least not for me. People with keen eyesight can note any inaccuracies in comments. (Have fun, kids; I didn’t note any inaccuracies in the quotes I checked.)

Acknowledgements

This is five pages long and dense with the names of the people who assisted then graduate student Larbalestier in her studies.

Introduction

Larbalestier sets out her goals for this book, as well as her academic perspective (including definitions for terms that would be unfamiliar to persons not of her academic lineage), and some context for the world of SF she will be studying.

Comments

I was peeved by the APA format citations, such as “deranged claim about women in SF!” (Asimov 1934; Anderson 1970), which distracted me. I prefer footnotes.

Faithful to Thee, Terra, in Our Fashion

A brief history of early SF and SF fandom, starting with the accretion of the genre in 1926. Larbalestier notes that, from the start, SF fans thought very highly of themselves. Also from the start, women were part of the community, acknowledged as such by the editors of the day. Although, as we will see, not always by their fellow fans and writers.

Mama Come Home

A discussion of fictional worlds in which women rule and men are subjugated. However, even when females are the dominant sex, it is because they have appropriated stereotypical masculine virtues. When men are submissive, they display what are culturally coded as feminine weaknesses. Deviations from the North American norm circa the middle part of the 20th century are generally seen as violations of nature.

Comments

Although there were pre-SF books like Herland, which depicts an alternate society superior to the North American norm, such books are the exception rather than the rule.

Painwise

A discussion of fictional works in which the solution to the battle between the sexes is to merge the sexes in some way. Bodies are hermaphroditic or they can switch from male to female. Sometimes one or the other of the sexes is entirely eliminated. Larbalestier points out that in practice, the first option seems to result in books where the default is to treat the characters as men, particularly if those characters are strong characters. Character traits are still sex-coded. For example, the protagonist of Left Hand of Darkness, Genly Ai, treats admirable traits in the hermaphroditic Gethenian natives as masculine and Gethenian traits Genly dislikes as feminine.

Comments

Larbalestier discusses Russ’s “When It Changed.” I rather wish that Larbalestier had gone on to compare Russ’s all-female utopia Whileaway (where the off-world men want to force the women of Whileaway to have sex with them) with Brin’s Glory Season (where the galactic civilization, the Phylum, plans to force the genetically and behaviorally distinct inhabitants of Stratos to interbreed with them).

Fault

Larbalestier examines how the SF community, in particular the men, reacted to the women lurking among them, as well as to the idea that SF could treat of topics like love and sex (subjects that seem inextricably entangled with the very existence of women [1]).

There were also some visionaries who saw women as a portable stress relief for the men.

For their part, the women contributing to the letter columns gave as good as they got. Got from misogynists like Asimov, for example.

Comments

The main difference between the early misogynists in SFdom and the current lot is that in the old days the he-man woman-haters were afraid if they got laid they might lose their focus on important matters, whereas the modern sort are outraged that they aren’t getting the sex to which they feel they are entitled. It’s not an improvement, but it is a change.

Asimov comes across as a smirking version of Dave Sim in his letters; his aversion to women does nothing to warn the reader that Asimov would later gain a bad rep for mauling unwilling women at cons. Asimov did get past this early misogyny to become an advocate for women’s rights, but he never made the intellectual leap that would have allowed him to understand that women did not enjoy being molested.

As for Poul Anderson: when Philip K Dick of all people says

We are too sure of ourselves, as witness Poul’s article-in-response. His article was lovely. Literate and reasonable and moderate and respectable and worthy in all respects except that it was meaningless, by virtue of the fact that it was just so much space gas. It was like telling the blacks they only “imagined” that somehow things in the world were different for them, that they somehow “imagined” that their needs, its articulations in our fiction, were being ignored. It is a conspiracy of silence, and Joanna, despite the fact she seemed to feel the need of attacking us on a personal level, shattered that silence, for the good of us all.

maybe you want to re-examine your assumptions. Poul doesn’t seem to have taken his responses from Russ or Dick to heart; the year after Dick’s letter Russ says of Poul:

He’s a nice man in a personal way but it’s hopeless; I feel like a rock climber at the 14,000-foot pass in the Rockies looking back through a telescope at some enthusiastic amateur in the Flatirons (foothills outside my study window) who’s proceeding Eastward, yelling “Hey! You’re in the wrong place! The mountains are this way!” It’s a sheer waste of time to argue with him; we’d better just let him go until he and his crampons hit Chicago.

The Women Men Don’t See

As much as people like young Asimov might have wanted SF to be a purely male domain, it never was. Larbalestier examines the history of women’s SF, as well as the reactions to the increasing presence of women in the genre (who were becoming, in the 1970s, arguably the most significant strand in the genre).

Comments

Everyone needs to read Charles Platt to determine for themselves to which of his asinine opinions they most object. That said, every time my attention is drawn to one of Randall Garrett’s repellent portrayals of women, my opinion of him drops. I am always surprised that it’s still possible for me to think worse of him, but there you go. I can only hope that “Queen Bee,” his thrilling tale of socially approved rape and lobotomy, is the absolute low point.

I’m Too Big but I Love to Play

Larbalestier looks at Alice Sheldon, who is most famous as the author James Tiptree, Jr.. She reviews Sheldon’s life and Tiptree’s role in the battle between the sexes in SF. The discussion covers both the period when people believed Tiptree was ineluctably male and the ensuing brouhaha when it was revealed that there was some reason to doubt the validity of that hypothesis.

Comments

This was a short chapter, but I still learned things that surprised me. Alice Sheldon was the protagonist of childrens books! I need to read her biography.

Her Smoke Rose Up Forever

This is a history and examination of the Tiptree Award, from its founding up to 2000.

Comments

You may ask “does she mention the Great Brin Kerfluffle, a reference to which once got the author to put in an angry appearance on my Livejournal?” Indeed she does.

Epilogue

A short afterword.

Appendix

An analysis of clause structures in “The Priestess Who Rebelled” and Who Needs Men?

Notes

Various notes that did not for one reason or another fit into the chapters for which they are notes.

Glossary

What it says on the tin.

Bibliography

My to-be-read list just got much longer.

Index

What it says on the tin. I only mention it because so many non-fiction books lack one.

General comments

The first thing I noticed on picking this up at the library is that it’s not very long: only 295 pages including notes, index, and such. The second thing I noticed is that it’s surprisingly heavy for a book that is less than three hundred pages. Foreshadowing for what is to come: this book may be short but it’s fairly dense. As a result my descriptions of each chapter are at best superficial.

The Battle of the Sexes in Science Fiction is available here. I recommend it highly.

1: Homosexuality in any form is largely absent as an option and when people are aware of it, the reaction/portrayal is generally quite negative.