Did someone say “UN Telepath”

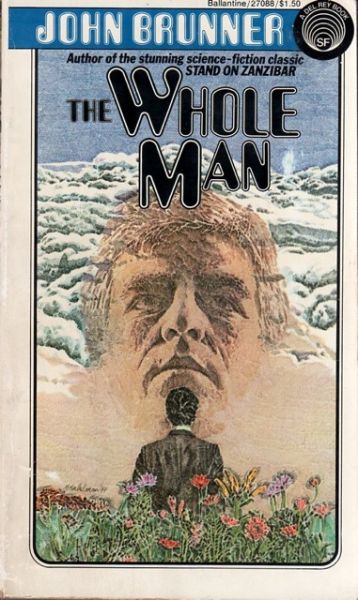

The Whole Man

By John Brunner

15 Dec, 2015

0 comments

Having recently reviewed one novel about UN telepaths, I am tempted to review an earlier book on the same theme: John Brunner’s 1964 The Whole Man. Written a generation before Emerald Eyes, it takes a much more optimistic view of mind-probing United Nation functionaries.

Perhaps the most obvious difference is that whereas Carl Castanaveras was the servant of the UN’s militarized police force, Gerald Howson is employed by the World Heath Organization.

Eventually.

The Whole Man is a fix-up of three novellas, 1958’s City of the Tiger, 1959’s The Whole Man, and 1959’s Curative Telepath. You may notice that is not what the three sections in this book are titled. Having never read the originals, I cannot say how heavily Brunner rewrote the originals for his novel.

Molem:

Despite the benevolent management of the United Nations, the world still has trouble spots. Gerald Howson is born in such trouble spot; he is the son of a dead terrorist and an indifferent mother who hoped, in vain, that her pregnancy would tie her ideologue boyfriend to her. A deformed hemophiliac, Gerald is consigned to a miserable life eking out a marginal living.

But nature has given Gerald a mental gift that compensates for his physical shortcomings: telepathy! As he is a projective telepath of considerable power, that makes an untrained, undisciplined Gerald a danger to the world.

Agitat:

The World Health Organization is more than happy to train Gerald; the WHO is always short of telepaths, particularly ones as powerful as Gerald. But Gerald has barely had time to come to grip with his abilities when he is asked to save premier telepath Ilsa Kronstadt from a mental intervention gone horribly wrong.

Mens:

Gerald is baffled when a fellow telepath deliberately surrenders himself to a dreamworld; he is affronted to discover his colleague sees the episode as a mere entertainment. The conversation sends Gerald on a journey of personal discovery. What good is it to be one of the UN’s elite curative telepaths when he cannot deal with his own problems?

~oOo~

Gerald (and the deaf girl he befriends) aren’t abandoned by the government on purpose. The UN doesn’t have any particular malice towards children of terrorists or towards the disabled (although they would certainly prefer it if people conformed to certain standards, physically and culturally). It’s just that the unnamed city is not at the top of their current to-do list. It’s easy for Gerald and people like him to slip through the cracks.

When I was a teenager, I thought for some reason Gerald was born somewhere in the US. Rereading this, I realized that this is never unambiguously stated. We are told very little about his home town. The one hint we get is this reaction by the citizens of Gerald’s city to UN pacification campaigns:

The fact of pacification was scarcely new, but it had been an elsewhere thing; it was reported in the papers and on TV, and it affected people with dark skins in distant countries with jungles and deserts.

Presumably, the city is populated by people aren’t elsewhere. That is, they do not have dark skins and they live somewhere that doesn’t have jungles or deserts. We are told that his birthplace does have a dry season, which I guess rules out the UK. Place names suggest an Anglospheric settler colony. It could as easily be somewhere in Australia as in the US.

By 1950s and 1960s standards, this book takes a fairly unprejudiced view of the various peoples of the world. People of all walks of life can conceivably end up working in the UN facility in Ulan Bator, which is described as one of Asia’s great cities.

This book is also notable as being about government telepaths who are not agents of tyranny. Brunner does acknowledge that there might be reasonable concerns about privacy and civil liberties, but his focus is on telepaths as therapists, not as secret police. This seems to be a world sans dramatic global crises, but bedevilled by local problems that spring up at a rate the UN can (barely) manage.

It’s kind of a shame, therefore, that the supposedly scientific underpinnings of the story are unusually dubious, even by the low standards of psionic SF. It’s even more of a shame that Brunner keeps drawing our attention to the unconvincing handwaving. This book was written during the period when Brunner put more value on speed than polish. The hurry is evident in the novel. It’s interesting as an alternate view of UN telepaths, but in the end, it’s a comparatively minor Brunner.

The Whole Man is available in a variety of editions.

1: Also published as Telepathist and as The Telepathist. I am about 80% sure that I first encountered it under one of those titles, but none of the covers shown on ISFDB remind me of the dimly remembered paperback.