More SF about women, by women

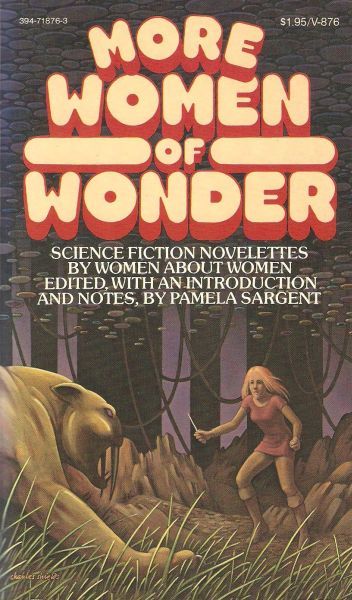

More Women of Wonder (Women of Wonder, volume 2)

By Pamela Sargent

28 Feb, 2015

0 comments

1976’s More Women of Wonder followed Women of Wonder by nineteen months [1] and offered a second sampling of speculative fiction written by women. As did the first collection, this draws from work published over the previous four decades although this volume has a higher fraction of recent works than the first volume. The stories included are with a single exception novelettes, a form which, like the novella, is in many ways an ideal length for SF [2].

Introduction (Pamela Sargent):

This forty-three page introduction is another look at women, both as authors and characters, in science fiction. Occasionally Sargent revisits topics covered in the first volume’s introduction; I never found these second looks boring. She always finds new perspectives from which to examine the material.

I understand that the copyright situation for this collection is semi-nightmarish (particularly since Moore, Brackett, and Russ have unfortunately become past tense). However, it would be possible to make these thoughtful introductions available online, which I very much wish Sargent would do. (A quick Google search indicates that this is not yet the case.) There are entire passages I would quote at length if I didn’t have to manually type the things. (My editor says, “OCR, OCR,” which is apparently one of those technologies people are using these days.)

Something I noticed in the first introduction that is still true: Sargent leans towards … how do I say this … I am going to go with “charitable interpretations of her male colleagues’ works and attitudes.” There’s a reason:

If it sometimes seems to the reader that past stories do not capture the complexity of our present day discussions of women, one must also remember when they were written, and give some credit to the authors who tried to deal with women seriously and imaginatively at a time when there was little encouragement on the part of editors and publishers to do so.

Were I in her place I would not be quite as understanding as Sargent, particularly towards those of her colleagues who hurled insults at fiction deemed too feminine, but I guess that’s why we needed a Joanna Russ.

“Jirel Meets Magic” [1935] (C.L. Moore):

Jirel, the warrior-woman of old-time France, pursues a sorcerer against whom she has a grudge, following him through a portal into a strange, alien dimension. There she encounters Jarisme, a being who is not so much a sorcerer as a demi-god, Jarisme’s cruelty towards her subjects enrages Jirel. Can the mortal Jirel stand against a power like Jarisme?

There must be an inherent aspect to prophecies such that even when people are familiar with the notion of self-fulfilling prophecies, they cannot see how such a notion might apply to the situation at hand.

I had read this story comparatively recently but I didn’t mind rereading it again. I enjoy Moore a lot and am thinking of reviewing another anthology of her works for a Sunday review.

One interesting detail: once Jirel steps into elfland, all of the significant characters are women. The sorcerer isn’t really a serious threat; his role in the plot is not as the main antagonist. He is only bait to draw Jirel into the real story.

“The Lake of the Gone Forever” [1949] (Leigh Brackett):

Convinced he will succeed where his father failed, Rand Conway mounts an expedition to mysterious Iskar, deep in the asteroid belt. He convinces ethnographer Peter Esmond, Esmond’s adoring girlfriend Marcia Rohan, and her father (and Esmond’s source of funds) Charles Rohan to join him. What Rand has carefully concealed from his companions is that there is a hidden fortune on Iskar for the man who knows where to look for it.

Rand is ignorant of the real history of his father’s visit to Iskar. He has never been told what actually happened in Iskar (something traumatic enough to break the older Conway). What’s waiting for Rand will change him forever.

This had somewhat more domestic abuse than I would consider ideal, but at least it’s portrayed as abuse.

I was pretty sure I’d somehow managed never to have read More Women of Wonder and this story clinches it. I know I’ve never read this Brackett because if I had, I would have moaned endlessly about her rotten science definitely remembered its creative although occasionally opaque world-building. Iskar is an arctic world but it is not as cold as it should be given that it’s probably 3 AU from the Sun Also, Brackett never explains how an asteroid can hang onto an atmosphere.

But that’s not the point of the story and I can forgive the iffy worldbuilding.

“The Second Inquisition” [1970] (Joanna Russ):

Mid-1920s: a young girl living with an abusive domineering father and her enabling mother is enthralled by their strange boarder, a tall woman of indeterminate race and curious unfamiliarity with commonplace knowledge.

To explain what sub-genre this belongs to would be to spoil a lot of it so … I will just say that it reminded me a little of something very famous by Moore. One of the Moore stories that manages to be even more downbeat than Russ can be, even this particular Russ, which is saying something.

“The Power of Time [1971] (Josephine Saxton):

Two stories reflect each other.

In the first, an English woman wins a contest whose prize is a week in exotic New York City, where she is escorted around the wonders of that city by a series of dashing men. Her experiences transform her and leave her reluctant to return to the UK and her life of social activism.

In the second, set five generations later on an Earth where her efforts (and those of other activists of other sorts) have been successful, a world now populated by a few million humans who have not migrated to the stars, a descendent of the woman pays to have Manhattan relocated to the location of her home town. This act of overwhelming hubris would have played out better had anyone bothered to do a geological survey first.

I’ve noted elsewhere that American SF has often had a conflicted attitude about the colonization of North America; this story would be a British example of that anxiety in action. It also belongs to the extremely specific sub-genre of SF stories inspired by the sale of Rennie’s London bridge to Robert McCulloch. It’s not the most famous example of such stories but it has its charms. I cannot help but notice that the American story linked to above is aghast at the possibility that one day a declining America will be strip-mined of its treasures by foreign plutocrats, just as American plutocrats once looted the cultural artifacts of other nations, British Saxton revels in the absurdity of it all.

“The Funeral” [1972] (Kate Wilhelm):

Following the death of an elderly teacher, a young woman is drawn into the search for information the teacher may or may not have preserved. It soon becomes clear that the young woman is not just dealing with an exploitative, abusive society dedicated to keeping women ground down while co-opting the energies of those women who might otherwise try to reform or overthrow the system. She is dealing with a society that is knowingly and willfully misogynist. If she stays, the protagonist will have to conform to a system designed to turn her into a monster and a victim. Escape seems impossible.

This was perhaps not the most cheerful story in this collection.

“Tin Soldier” [1974] (Joan D. Vinge)

The stars are within humanity’s reach — unless you are a cyborg or worse, a man, For these unfortunate souls, access to the worlds of other stars means traveling as frozen cargo to avoid being killed by the physiological effects of relativistic space travel. While the men comfort themselves with grotesque displays of masculinity, women spread human civilization across the Milky Way.

Soldier is, despite his name, a bartender on a backwater world. Brandy is the starfarer with whom he strikes up an unlikely friendship, one that would be more than that if not for the customs of the starfarers. Time dilation means that mere years pass for travelers while decades pass on planets; starfarers would return to find lovers aged beyond recognition or dead. Starfarer customs are intended to avoid unnecessary pain. In this case, however, Soldier is a cyborg and some cyborgs age unnaturally slowly. In this case, custom has an effect quite opposite to the original intent; the pair have spent long centuries smitten but forbidden to have a more intimate relationship.

The slow-aging effect of cyborgification is likely but not guaranteed. Nevertheless, I imagine a lot of people in the world of this story would have indulged in unnecessary cyborgification just to try to get the lifespan enhancement. Also to be able to crush skulls like eggshells; you never know when you’re going to need that.

Vinge’s question “what would happen if it turned out only women were able to be space travelers?” is an interesting one. In this case, I think that Vinge got her answer wrong, She imagines that entire worlds will devote themselves to manly manism, competing for status with the dominant females. However, given the fall in status of secretarial jobs once that field was dominated by women, or what happened to the prestige of Soviet-era doctors once women entered the field en masse, I would expect that men would simply dismiss space travel as unimportant and slash wages for starfarers.

“The Day Before the Revolution” [1974] (Ursula K. Le Guin):

This tells a small part of the backstory for Le Guin’s novel The Dispossessed, It is an account of the Anarchist revolution [3] that would lead to the anarchist exodus to the moon Anarres and the establishment of a society that, while in no way perfect, is functional enough to survive on an unwelcoming world. The story is told from the point of view of the woman who inspired the Revolution. It is an account of her final days, which are passing as the movement she started is coming to fruition.

At the risk of enraging millions of readers and also my editor [editorial comment: <^^^^^> glyph of rage], the Odonians of The Dispossessed and this story always struck me as the sort of tediously doctrinaire, earnest fanatics I would go a long way to avoid; Odo herself isn’t much like the people she inspired. Someone else can argue over whether that’s because she was in many ways superior to her followers or if having been raised in the old ways, she could never quite rid herself of their effects. I think the story is a bit ambiguous on that point, which seems apt for a prequel to The Dispossessed (which is billed as story about an ambiguous utopia).

This is the lone short story in the anthology but if an editor is going to make an exception for one author, it makes sense to do so for Le Guin.

~oOo~

I’d like to think Sargent’s sort of endeavor was no longer necessary but in fact it seems as if an awful lot of effort has gone into erasing the role of women in SF. Let us remember that whole wonderful period, beginning in the 1960s and extending into the 1980s, when women like:

Lynn Abbey, Eleanor Arnason, Octavia Butler, Moyra Caldecott, Jaygee Carr, Joy Chant, Suzy McKee Charnas, C. J. Cherryh, Jo Clayton, Candas Jane Dorsey, Diane Duane, Phyllis Eisenstein, Cynthia Felice, Sheila Finch, Sally Gearhart, Mary Gentle, Dian Girard, Eileen Gunn, Monica Hughes, Diana Wynne Jones, Gwyneth Jones, Leigh Kennedy, Lee Killough, Nancy Kress, Katherine Kurtz, Tanith Lee, Megan Lindholm, Elizabeth A. Lynn, Phillipa Maddern, Ardath Mayhar, Vonda McIntyre, Patricia A. McKillip, Janet Morris, Pat Murphy, Rachel Pollack, Marta Randall, Anne Rice, Jessica Amanda Salmonson, Pamela Sargent, Sydney J. Van Scyoc, Susan Shwartz, Nancy Springer, Lisa Tuttle, Joan Vinge, Élisabeth Vonarburg, Cherry Wilder, Connie Willis, Marcia J. Bennett, Mary Brown, Lois McMaster Bujold, Emma Bull, Pat Cadigan, Isobelle Carmody, Brenda W. Clough, Kara Dalkey, Pamela Dean, Susan Dexter, Carole Nelson Douglas, Debra Doyle, Claudia J. Edwards, Doris Egan, Ru Emerson, C.S. Friedman, Anne Gay, Sheila Gilluly, Carolyn Ives Gilman, Lisa Goldstein, Nicola Griffith, Karen Haber, Barbara Hambly, Dorothy Heydt (AKA Katherine Blake), P.C. Hodgell, Nina Kiriki Hoffman, Tanya Huff, Kij Johnson, Janet Kagan, Patricia Kennealy-Morrison, Katharine Kerr, Peg Kerr, Katharine Eliska Kimbriel, Rosemary Kirstein, Ellen Kushner, Mercedes Lackey, Sharon Lee, Megan Lindholm, R.A. MacAvoy, Laurie J. Marks, Maureen McHugh, Dee Morrison Meaney, Naomi Mitchison, Elizabeth Moon, Paula Helm Murray, Rebecca Ore, Tamora Pierce, Alis Rasmussen (AKA Kate Elliott), Melanie Rawn, Mickey Zucker Reichert, Jennifer Roberson, Michaela Roessner, Kristine Kathryn Rusch, Melissa Scott, Eluki Bes Shahar (AKA Rosemary Edghill), Nisi Shawl, Delia Sherman, Josepha Sherman, Sherwood Smith, Melinda Snodgrass, Midori Snyder, Sara Stamey, Caroline Stevermer, Martha Soukup, Judith Tarr, Sheri S. Tepper, Prof. Mary Turzillo, Paula Volsky, Deborah Wheeler (Deborah J. Ross), Freda Warrington, K.D. Wentworth, Janny Wurts, and Patricia Wrede,

to name a few, entered SF for the first time [4]. To quote a recent comment by noted author Eleanor Arnason (QWP):

“As I said above, what I find interesting about the Bradford discussion is — 40 years of history have disappeared. Both the people defending women SFF writers and the people saying women can’t write SFF sound as if they are back in the 1970s. I am disturbed by this, because my writing history is one of the things being disappeared. I have vanished as a writer in this discourse.”

Part of my purpose in reviewing books like the Women of Wonder series, Kidd’s Millennial Women and Eye of the Heron, and McIntyre and Anderson’s Aurora: Beyond Equality is to remind people what was happening in the 1970s, to do my bit to ensure that that period is not forgotten. However convenient that willful amnesia might be for certain people within the speculative fiction community.

1: You know why I have footnotes? To excise my digressions from the text, in this case my sudden curiosity as to whether it was significant that WoW came out in January 1975 (which means it was probably available a month or so earlier, or in time for the Christmas rush) while MWoW came in August of 1976, so … in time for beach reading? Although either release date could be aimed at getting the books into academic bookstores in time for the start of that term’s classes.

Or perhaps Vintage had holes in its schedule for Jan 1975 and Aug 1976.

2: Enough room to develop their stories, not enough room to sabotage them with bells and whistles intended to enhance the plot that instead undermine it. Getting into the details of world-building enough to reveal the bits that don’t work; adding subplots that don’t go anywhere, and so on. For example, everything that makes “Flowers for Algernon” memorable is in the short version; the only way in which the novel is superior is length. There’s an art to knowing when to shut up.*

3: What struck me about this tale that rejects hierarchy, wealth, and power is the name of the editor who purchased it. A fellow named James Patrick Baen. I could write an interesting “stories I am boggled Jim Baen bought” review series …. had I but world enough and time.

4: This list is deficient in names from the 1960s, but, in my defense, I know I can rely on my fearless commenters to fill the lacunae.

*: In writing reviews, the trick is to work what aspects of the work not to discuss. A thorough discussion could easily be longer than the original and, unless one is lucky enough to have one’s own review site, one is likely operating with a work count limit.**

**: Hey, look, my footnotes have a footnote, which has a footnote!