Return to Warlock

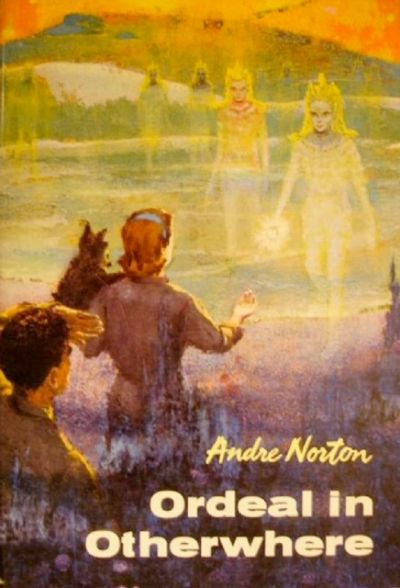

Ordeal in Otherwhere (Warlock, volume 2)

By Andre Norton

12 Jun, 2015

0 comments

1964’s Ordeal in Otherwhere starts off at a sprint. When we first encounter young Charis Nordholm, a cult leader and his idiot followers1 have staged a coup and murdered her father in the process. Charis is on the run and faces an unpleasant choice: surrender to the cultists and accept whatever horrible fate they deem suitable for a heretic OR try to hide in the local jungle, where she will almost certainly be eaten.

It turns out there is a third option, which is to be captured by the rebels and then sold to an off-world trader2.

Luckily for Charis, Norton can be grim but not too grim. Rather than being sold to the slave brothels of some slum like the Dipple, Charis is sold to Jagan, a Free Trader. He has a legitimate (if risky) use for a highly educated woman. Charis heads off to the stars, leaving behind a colony run by a madman and almost certainly doomed due to its tiny population.

Jagan hopes to open a profitable trade with the rulers of the planet Warlock, Those rulers, the Wyverns, are female and will not deal with men. Deal with them as equals and trade partners, that is; men are treated as inferiors, brutes to be kept down. Trying to open communications with the Wyverns is dangerous; the first human woman who tried to deal with the witchy rulers went mad. However, Jagan is willing to put Charis at risk in return for a potentially lucrative trade in goods and technologies ranging from fine cloth to teleportation. Charis has little choice in the matter.

Charis plays for time, hoping to keep her mind intact long enough to escape from Jagan and the Wyverns. Fortunately, escape proves unnecessary; she succeeds where her predecessor failed. Trade may be possible in the future but for now, at least Charis can talk to them without having her mind broken.

This turns out to benefit the Wyverns as much it saves Charis. The witches are powerful and technologically (or perhaps magically) sophisticated. They are also arrogant, over-confident, xenophobic, sexist, and comprehensively ignorant about the universe beyond their world. Previously, that has not mattered. Now, ambitious off-worlders armed with psionics-dampening machines have allied with the Wyvern males. Where poor doomed Jagan hoped for trade, these newcomers plan conquest.

And there is little room in their plans for Charis.…

~oOo~

This is a sequel to Storm over Warlock, whose protagonist Shan does put in an appearance. In fact, Shan and Charis get on quite well, which explains something I did not understand when I reviewed Storm; Warlock and Ordeal fit into the Forerunner series because Forerunner Foray, the next book in the series and the one that gives the series its name, features their child as protagonist. Otherwise, there’s not much sign of the Forerunners in this volume.

[Note added much later: I have been persuaded that “Warlock” is a better name for this series so I changed it]

The Wyverns really are unpleasant; they’ve enslaved their men, they treat visitors like playthings, and they don’t seem to be particularly bright when faced with an unexpected crisis. It’s interesting that Norton eschews utopian models for the matriarchies in her invented worlds (with the possible exception of the matriarchy in Secret of the Lost Race). They aren’t any more benign than male-run societies or any less blinkered by prejudice.

Even if no more psionic dampers are imported — I foresee strict bans being imposed on their importation to Warlock in the near future, for all the good that will —the knowledge that they are possible at all, not to mention that a number of human prisoners shook off the Wyvern domination, seems likely to ensure that shock waves will continue to ripple through Wyvern society. Charis does her best to convince the females they need to rethink their social code, but frankly, I am not sure how adaptable the Wyverns will prove to be.

There’s an interesting passage in Norton’s essay “On Writing Fantasy” :

These are the heroes, but what of the heroines? In the Conan tales there are generally beautiful slave girls, one pirate queen, one woman mercenary. Conan lusts, not loves, in the romantic sense, and moves on without remembering face or person. This is the pattern followed by the majority of the wandering heroes. Witches exist, as do queens (always in need of having their lost thrones regained or shored up by the hero), and a few come alive. As do de Camp’s women, the thief-heroine of Wizard of Storm, the young girl in the Garner books, the Sorceress of The Island of the Mighty. But still they remain props of the hero.

Only C. L. Moore, almost a generation ago, produced a heroine who was as self-sufficient, as deadly with a sword, as dominate a character as any of the swordsmen she faced. In the series of stories recently published as Jirel of Joiry we meet the heroine in her own right, and not to be down-cried before any armed company.

When it came to write Year of the Unicorn, it was my wish to spin a story distantly based on the old tale of Beauty and the Beast. I had already experimented with some heroines who interested me, the Witch Jaelithe and Loyse of Verlaine. But to write a full book from the feminine point of view was a departure. I found it fascinating to write, but the reception was oddly mixed. In the years now since it was first published I have had many letters from women readers who accepted Gillan with open arms, and I have had masculine readers who hotly resented her.

But I was encouraged enough to present a second heroine, the Sorceress Kaththea. And since then I have written several more shorter stories, both laid in Witch World and elsewhere, spun about a heroine instead of a hero. Perhaps now will come a shift in an old pattern; it will be most interesting to watch and see.

Year of the Unicorn was published after Ordeal. I wonder if the male readers who objected to Gillian had also objected to Charis. In Ordeal, Norton essentially reduces Shan to a supporting character, despite starting the series with a book focused on him. That seems like the sort of thing that would rile male chauvinists, but if it did, I haven’t heard or read about it. Perhaps the competent, resourceful Charis won over even the hardcore chauvinists. One of things *I* particularly liked about this character is that she is valued not for her looks, but for her education.

By this point in her career, Norton had a lot of experience writing at novel length, more than many of her contemporaries (writers who had been writing for the pulps, before many of the pulps went belly-up). Norton generally eschewed shorter works in favour of novels, and knew how to make novels move along briskly — as does Ordeal.

Ordeal does not seem to have had an edition listed at ISFDB in the last decade. Once again, used bookstores, online or brick-and-mortar, and your public library are your friends.

1: Colonist belief in the cult is buttressed by the fact that a mysterious malady has struck down the sons of all those who oppose the leader. This seems like the sort of detail that would turn out to be orchestrated (possibly to serve as an indicator of divine favour). Dunno if Norton ever followed up on this.

2: Technically, coerced into accepting a one-sided labour contract. Not quite slavery, at least legally.