The Riddle-Master of Hed, Heir of Sea and Fire, Harpist in the Wind

Riddle of Stars

By Patricia A. McKillip

31 Jul, 2014

0 comments

I have owned this ever since that day long ago when I didn’t remember to send back in the little SFBC card, which was one of my standard ways to diversify my library. Perhaps the success of that method explains why I am so comfortable letting other people choose my reading material now?

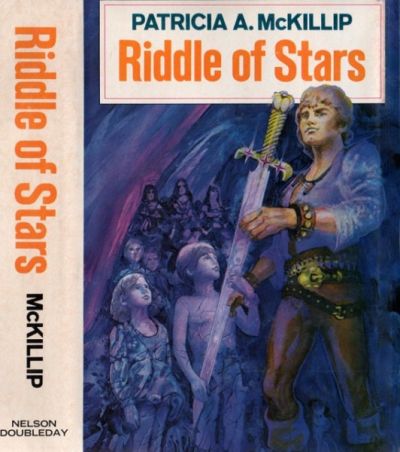

My copy is missing its dust jacket but the art is on isfdb and I wonder if the lackluster cover is why I passed this over for 30+ years?

I prefer the art on this this later edition but it’s still not quite right.

I prefer the art on this this later edition but it’s still not quite right.

I am not sure I actually ever read Riddle of Stars (I have a number of late-1970s SFBC books set aside for a rainy day). In fact a detail at the end of the first novel suggests strongly that I did not read it because it’s the sort of detail that is quite memorable and I did not remember it.

Riddle of Stars contains material that was initially published as Riddle-Master of Hed (1976), Heir of Sea and Fire (1977) and Harpist in the Wind (1979). I was originally asked for a review of Riddle-Master of Hed but instead I elected to reread (or possibly just read) the whole omnibus. I had two reasons: one, I could, and two… I will get to two.

When we meet one of the protagonists, Prince Morgon of Hed, in Riddle-Master of Hed he is one of the humbler sort of aristocrats. He may be the prince but he is bound to his land and responsibilities by magic and Hed is a very small and very poor kingdom. Morgon is expected to help with the manual labour and his most frequent dinner guest is the local pig herder.

Annoyingly for his subjects, Morgon has ambitions above his station. Princes of Hed are supposed to be dull and incurious, as devoted to the details of farming and trade as it takes to ensure the prosperity of his people. Morgon is devoted to his land, always careful never to use its resources for his own private hobbies, but he is also a scholar who went abroad to study, and someone to whom visiting a potentially lethal specter to riddle a crown away from them sounds likes a fine idea; having won the crown, he keeps it hidden safely under his bed.

Much to Morgon’s surprise, he discovers that when he won Peven of Aum’s crown from the dead king, he also won the hand of Raederle, sister to one of Morgon’s fellow scholars but more importantly the daughter of King Mathom of An and the second fairest woman in the land. The prospect of marrying Raederle is not an unpleasant one to Morgon and so he sets out with the enigmatic bard Deth to resolve the situation with Raederle.

Alas for Morgon, he is unknowingly entangled in a vast struggle whose roots go back before recorded history began and whose consequences involve the fate of the world. He and Deth are ambushed in mid-trip and while they manage to prevail, what follows is a series of unpleasant educational experiences for Morgon. With murderous shape-shifters on one side and Ghisteslwchlohm, the grand villain in the shadows, on another, Morgon is fated as the Star-Bearer to be a particularly valuable gaming piece, one whose ignorance of his own significance places him in particular danger. Morgon would prefer to refuse the call but that is not a choice he has.

Heir of Sea and Fire focuses on Raederle, daughter of King Mathom of An and the second fairest woman in the land. Determined to know the true fate of her betrothed, she sets out to find him. You might expect that this would mean the book is entirely focused on Morgon but that is not the case. There is much more to Raederle than she knows and the unexpected and unwanted revelations about her heritage leave her confounded about her proper role in the on-going struggle.

Harpist in the Wind features both Morgon and Raederle as central figures, both reluctantly and irreversibly transformed almost beyond recognition from the straightforward figures at the beginnings of their respective books. Inaction will likely doom all that they hold dear but while both have enormous reserves of power to draw on if they so choose, they are deterred from fully exploiting their potentials by an awareness that power without sufficient knowledge and restraint is as destructive as any of the forces contending over the realm.

The first volume ends with one of the more remarkable reveals in fantasy and I cannot imagine what it must have been like for readers way back in 1976. I had the omnibus in hand and knew there would be more. A reader in the Disco Era would have no such assurance.

I do have to wonder why in a culture where riddles and word games are so important, nobody seems to pay close attention to names. I can you if I lived in a world where words have power the way they do in this world, there is absolutely no way I would go on a camping trip with anyone whose name is a homophone for mortality.

I despise most Celtoid fantasies but this I was unwilling to stop reading and despite having read a staggering number of fantasies, McKillip still managed to subvert my expectations. McKillip did have the advantage that she was writing in the very early stages of the great commercialization of fantasy, before editorial expectations for the fantasy genres had quite crystalized. I would not be surprised if this trilogy is among the works lesser authors borrow from to paste together their derivative little tinker-toy universes but where modern commercial fantasy often reads like the crib notes from not particularly inspired homegrown role-playing game settings, McKillip hints at a grand setting while keeping the focus on a comparatively constrained region and she trusts the reader to trust her enough not to require her to spoon feed them information throughout the book.

Another aspect of this work that is remarkable is McKillip’s mastery of language, which is on a level well above most authors. Mine isn’t, so I will just say I don’t often pause to reread passages but in this work I did.

I regret that this is my first reading of this novel because it feels to me like one of those works one can safely reread in a generation, discovering previously overlooked foreshadowing and subtleties of character missed on a first read. I plan to check this hypothesis in 2034 and invite whoever is still around to join me.

The omnibus was reprinted under the title The Riddle-Master’s Game in 2001 as part of the Gollancz Fantasy Masterworks series (McKillip was one of just six women included alongside a much larger number of men) but I am unsure if it is in print at this time.

It is in print, I just did not look in the right place.