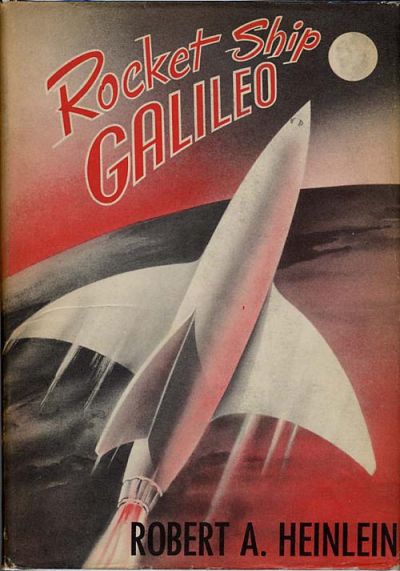

Rocket Ship Galileo

Rocket Ship Galileo

By Robert A. Heinlein

15 Aug, 2014

The Great Heinlein Juveniles (Plus The Other Two) Reread

0 comments

First published in 1947.

Post-war but not too post-war America! While the UN police guarantee global peace and systems as different as the American and Russian ways of life live together amicably, three young men, products of America’s impressive new school system, are focused (as so many young men of this time were) on their homemade rocket. While the rocket itself goes all kerblooie, the young men — Ross Jenkins, Art Mueller and Maurice Abrams – count the experiment as a success, at least until they find the unconscious man on the doorstep of their test facility, apparently brained by a fragment from the exploding rocket.

Luckily for the boys, this isn’t a juvenile novel about three teens going on the lam for manslaughter and the unconscious man, who is none other than Arts’ uncle Don Cargraves, Noted Atomic Scientist!, is only knocked out, not dead or permanently brain-damaged. Furthermore, although he decides not to share this information with the boys, Don suspects he was not the victim of an errant fragment of rocket but rather the target of a shadowy plot that will stop at nothing to keep from Don from carrying out his audacious plan.

“Depraved indifference” and “the uncle who used his relatives as living meat shields” are going to be book-ends for this series of reviews.

Don believes he knows how to convert a standard chemical rocket to an atomic model able to reach the Moon itself and while his former employers are not interested in this because they cannot see how there could sufficient ROI to justify the effort, they don’t have a problem with Don trying to win the prize money for reaching the Moon on his own time. Unfortunately, paying for a surplus rocket and the means to convert it into a nuclear thermal rocket will take all of Don’s money, leaving him no funds to pay trained personnel. Which is where the boys come in. Engineers and certified pilots may be expensive but talented young men with a teenager’s grasp of risk are surprisingly affordable.

Constrained by space as he was in these novels, Heinlein allotted parents page time in direct proportion to how much of an impediment they were. The boys’ parents are not very keen on the idea of Don using the boys in his scheme to reach the Moon, both because it’s obviously risky and because the boys could be investing their time in preparation for their lives as adults. Of course, Don brings the parents around1 because there’s no novel if he doesn’t.

“The childless uncle who lectures women on how to raise kids” is also going to book-end the series. It’s the same uncle who features in “Depraved indifference” and “the uncle who used his relatives as living meat shields”, of course.

The government is surprisingly open to the idea of a talented atomic scientist and three young men faffing about with kit-bashed atomic rockets out in the desert (next to the test site of the Super Bomb, so at least it’s not like the place is going to get more radioactive) and thorium turns out to be surprisingly easy to get hold of in bulk. While the minefield and the glassy crater of the Doomsday Bomb has cleared out most of the local wildlife, the project does has an ongoing problem with varmints of the two legged variety, but despite break-ins, bombs, and some light maiming, the crew soldiers on and by page 882 the Rocket Ship Galileo takes off for the Moon!

A lot of SF works, some by Heinlein himself, would focus on the technical details of a visit to the Moon but in this specific case it turns out the Moon, whose history is quite different than imagined by conventional astronomers, is inhabited and by some pretty troublesome sorts.

I am not going to pull a Disch here and claim nobody likes Rocket Ship Galileo3 but I suspect the number of people for whom this is their favourite Heinlein novel is pretty small. Heinlein is working out how to write this juvenile stuff and it shows in a lot of ways; the characters are pretty thin, the plot is adequate at best and as is the fate of all near-future SF, events have passed it by.

That said, I think the novel has some interesting features and can reward a reread if approached in the right way.

While Heinlein would come up with better solutions to the problem of how to write juveniles, there is a detail that shows up right away. A number of his young adult novels have a main character, the main character’s best friend and a third friend who is culturally or physically distinct from the other two. In this the lead is Ross, the best friend is Art and the Other is Maurice, who while the text can’t come out and say it is clearly intended to be a Jew.

Modern eyes might find the casualness with which the kids are allowed to play with rockets a bit startling but back in the 1930s and 1940s a lot of kids were doing stuff like this. My father and his buddies, for example, managed to cook off a full load of carbon-rich rocket fuel in the basement of a freshly painted house around the time this novel was published. Many of the details of how the boys carry out their research so as to minimize (although not completely eliminate) an amateur trepanning could come straight from Brinley’s 1960 Rocket Manual for Amateurs, a must-have resource for every young person who feels that they have too many fingers.

I am not entirely clear why Heinlein thought zinc would be a good reaction mass for the rocket. I mean, I did read the discussion in the book but it seems intuitively obvious that the exhaust velocity of a nuclear thermal rocket using zinc would be pretty terrible but it couldn’t be or this book would have been written differently.

An issue that comes up with real world nuclear thermal rockets is the matter of shielding. Galileo is only shielded on the side towards the crew, which constrains where passengers may approach and leave the rocket; this is covered briefly but it is covered.

This is pretty dated but I think Rocket Ship Galileo has gone through the Uncanny Valley of Near-Future SF and right out the other side, disconnected from history but in illuminating ways. For example, although Don is not keen on Russians, there’s no hint of the Cold War to come. The novel has an innocent faith in the UN that the author would later cast aside, and demonstrates an optimism about America’s schools that I can assure you will very quickly vanish from this series. Best of all, there’s no hint from the book how cool Heinlein was on the US getting involved in the fight against Hitler4 and clearly the author had no inkling that far from relying on a covert network of Nazi holdouts to finance Nazi technologists, people like SS-Sturmbannführer Werner Von Braun would be openly paper-clipped into the US.

The discussion of the Moon is interesting mainly for a detail about the Lunar farside, which reasonable people expected to look much like the 60% we can see from the Earth. In fact it is quite distinct and why that is is a puzzle scientists are still working on.

The moral that atomic war is in many sense regrettable seems reasonable, as its the thesis that blowing the atmosphere off one’s home world should be avoided if possible, the gang’s speculation about the Moon’s history seems pretty dubious. Sure, the archaeological stuff is intriguing but even in the 1940s it must have been clear a planet with the low escape velocity of the Moon couldn’t hold onto an atmosphere for long. Right?

People who have read Number of Beast who did not subsequently batter themselves around the head to rid themselves of the memory may be interested to know that a somewhat similar (although nowhere near as interminable) argument over who is driving pops up here when Don is struck by a brief moment of conscience over dragging kids into mortal danger.

This is a minor Heinlein but I don’t regret the evening I spent peering at the tiny, tiny print. The story might be simple and implausible but I still remember how upset I got as a kid when [rot13 for spoilers] gur Tnyvyrb vf qrfgeblrq. If it’s wrong for an atomic scientist and three expendable teens to head to the Moon in a homemade rocket to shoot Space Nazis, then I don’t want to be right5.

Rocket Ship Galileo is available from the troubled Virginia Editions of Heinlein’s works. At this time I am unclear about the status of less expensive editions; I assumed Baen had the rights but apparently not.

- There’s a section of Rocket Girls that I suspect was influenced either consciously or unconsciously by the scene where Don makes his case that his Moon scheme is a worthy thing for the boys to risk their lives on.

- of the Ace MMPK. I see on checking it Ace didn’t bother to list the year their MMPK came out but isfdb assures me it was 1970.

- If only because I know Spider Robinson is out there and he’d like Robert Heinlein’s 380 Blank Pages Coated with a Contact Neurotoxin.

- At least if chapter 20: Out and About: the Long, Strange Trip in Patterson’s biography of Heinlein is to be believed.

- Modern readers might have an issue with how the gang tortures one prisoner – ha ha, I couldn’t even type that with a straight face.