“She knew a happy ending when she saw it.”

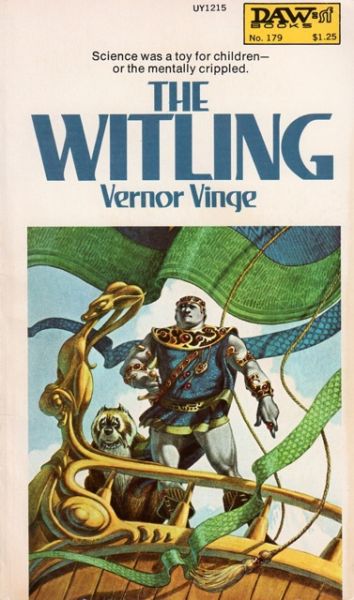

The Witling

By Vernor Vinge

6 Sep, 2015

Because My Tears Are Delicious To You

0 comments

Someone — I cannot recall who and Googling has not helped — used to assert that each Vernor Vinge novel was significantly better than the last. I don’t think this is quite true1, but it is often enough true to be useful. The corollary is that the older the Vinge novel, the more likely it is to be bad. Now you must be wondering: just how bad is the worst Vernor Vinge novel?

I have 1976’s The Witling at hand, so I can tell you the answer to that question:

“Pretty damn bad.”

Spoilers

Pity poor Yoninne Leg-Wot. She is a talented enough pilot to qualify for a scouting expedition to Giri, an unexplored world close to the new human colony world of Novamerika. She is also enough of a grumpy uggo that no self-respecting man is ever going to date her.

Well, no self-respecting human man. To the alien prince Pelio, Leg-Wot is an exotic beauty. That’s good, because the scouting expedition to Giri overlooked something vital about its natives, who are the third alien race humanity has ever encountered. Most of the expedition dies during a doomed attempt to leave Giri and if the two survivors, Let-Wot and the elderly Bjault, are to escape back to Novamerika, it will take all of Bjault’s cunning and all of Leg-Wot’s feminine charms.

And the pair do have to escape as soon as possible because the local ecology incorporates more heavy metals than humans can safely digest. The alternative to somehow contacting Novamerika isn’t a lifetime of exile, but death by poisoning in the near future.

Pelio finds Leg-Wot alluring not merely because she is to his eyes an off-world beauty but also because they share a common disability; neither of them can teleport. Had Pelio been born a commoner, his status as a teleportational cripple, a witling, would consign him to the lowest ranks of society. As heir to the throne, Pelio has enough status to protect him from the common prejudices in this matter, although his family is ever eager to find a legal pretext to remove him from the succession.

Interesting fact about the local legal system: the only way to remove someone from the succession is to kill them.

There is a way for the two humans to escape the planet. It requires both human technology and alien teleportation. It will also require betraying Pelio, a man who seems to trust the two humans.

A man Leg-Wot might be able to love.…

~oOo~

I would like to assure readers at this point that there really isn’t any mushy stuff in this book, despite the previous sentence. Vernor Vinge has the light romantic touch of a Forward, a Clement, or a Rothman, which is to say that if he has any romantic writing chops at all it is in homeopathic quantities.

What this novel is really is the effects that a restricted form of psionic teleportation would have on a society 2.

I would not be surprised at all to learn that Vinge began thinking about the teleportation-specific parts of this short novel after reading Larry Niven’s whimsical essay “Exercise in Speculation: The Theory and Practice of Teleportation,” which first appeared in the March 1969 issue of Galaxy and then in the 1971 collection All The Myriad Ways. Having worked out for himself how this novel’s form of teleportation works, Vinge then allows his two human characters encounter it. As they learn about it, all of Vinge’s cool ideas will be revealed. A variation on “as you know, Bob” as traditional as it is useful!

The effects of teleportation are not limited to simply granting the denizens of an iron-age culture jet-age access to their entire world. Rather like Kevin O’Donnell, Jr. and Steven Gould, Vinge understands that teleportation can be a terrible weapon. Even though this specific version is somewhat limited by conservation laws and other considerations, it isn’t hard for the aliens to work out lethal applications of their talent, from swapping parts of the brain around to bringing down fragments of their moon with WMD-level effects.

Now, I have a pretty well-developed tolerance for old style hard science fiction; heck, I even own a copy of this:

If Vinge had stayed in his tinker-toy universe, this book would be fine. Unfortunately, Vinge also finds room for some fairly troglodytic gender politics. And that’s by the standards of the 1970s.

I got a reminder early on that this novel was going to go in an unfortunate direction when the human scouts discuss what they have learned of the local language and lament

“I know, I know: ‘there are subtleties we don’t yet grasp.’ The only people we’ve consistently been able to eavesdrop on are children and women.”

Leg-Wot is bright and good at her job, but she is also ugly and very bad-tempered. She is the one woman in the colony whom Bjault can accompany without scandal, because no one could believe that Bjault would be attracted to her.

While Vinge does give Leg-Wot skills that might compensate for her lack of charm, she doesn’t really get to demonstrate her abilities. She’s a pilot and there’s not a lot of flying to be done on the planet of the iron-age teleporters. Instead, she gets to reluctantly attempt to seduce an alien who unexpectedly finds her attractive. Why have a girl in an adventure story unless the plot requires a romance?

But it gets so much worse than choosing to feature a female character with non-stereotypically feminine strengths 3, then forcing her into a standard role.

Leg-Wot does her best to be a plucky adventuress and what this earns her is a brain-scrambling from a native she has foiled once too often. Normally, this kind of attack would kill the victim but Leg-Wot manages to survive, albeit at the cost of her memories and her higher intellectual abilities. But that’s OK because the prince still thinks she’s pretty. And isn’t that what really matters?

Lest you think I am being unfair, this is the final two paragraphs:

She was glad when the stranger left. She vaguely realized that he belonged somewhere in the vanished past, with all the memories, skills and experience that had made her a different person. But that other she had suffered much, and had never really enjoyed herself. Now there was another chance.

She looked up at Pelio’s grey-green face, and took his thick hand in hers. She had lost so much that was of value but she was no fool. She knew a happy ending when she saw it.

Back in the day, I thought of Vinge as the less talented husband of Joan D. Vinge, the J. O. Jeppson to Joan’s Isaac Asimov. Because of books like this. Well, at least Vernor’s career wasn’t overshadowed by an early success, as Asimov’s was by “Nightfall” or Haldeman’s by The Forever War . He also managed to avoid what I call the David R. Palmer trap, in which an early work is wretched enough to put the author’s career on hold for few decades. Although given the quality of this novel I don’t see how he avoided authorial oblivion.

Inexplicably — because if I was his publisher I would be doing everything I could to suppress the information that this novel ever even existed — Tor saw fit to reprint The Witling.

1: Not all the early books are bad; 1969’s Grimm’s World breaks the pattern: it’s not good, but it’s not The Witling bad.

2: Even at this early state of his career, we can see tropes that were to feature in much of Vinge’s fiction, tropes like the inexorable rise and fall of human civilizations.

Although it is *odd* that despite the setting being many thousands of years in the future (years that comprised at least one two-thousand-year hiatus in civilization), people are still naming their colonies after contemporary nations like America. Eve n the spelling is still almost the same as it is now. It’s as if Canada were to settle a distant planet and call it after a town that vanished before the Younger Dryas.

3: Although there is another woman who is a pilot so it may be in this society piloting is considered women’s work.