The anti-Lovecraft

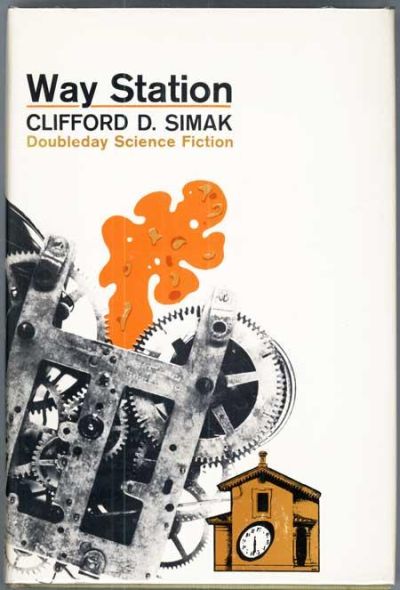

Way Station

By Clifford D. Simak

25 Jan, 2015

Because My Tears Are Delicious To You

0 comments

Clifford D. Simak’s 1963 Hugo-winning novel Way Station in many ways exemplifies the strengths for which Simak was known, as well as some of his characteristic weaknesses. Way Station is also an example of something that is quite rare amongst Hugo-winning novels: it is very much out of print, along with most of Simak’s oeuvre, a development that has left it undeservedly obscure. I may not be able to place the book in your hands but at I least I can remind people it exists.

Enoch Wallace lives in one of the more backward parts of Wisconsin, a region that the 1960s (and much of the 20th century) have passed by. A familiar figure to his neighbors, he lives a quiet, seemingly unremarkable life. He attracts the attention of the American government when officials notice that, as far as they can tell, Enoch has been living his quiet life on that farm since 1840 (except for a few years spent fighting for the Union during the Slavers’ Uprising). Yet he doesn’t look a day over thirty0.

Then the government discovers the dead alien buried behind Enoch’s place.…

The 1860s were a traumatic time for poor Enoch; the girl he loved died of diphtheria while he was away at war, followed in short order by his mother. Then Enoch’s father was killed in a farming mishap. The entity Enoch came to know as Ulysses found in Enoch a man alone and solitary, but also curious and good-natured, an ideal candidate for a very special task: operating a way station in the Galactic Federation’s teleportation network. Because the Earth is a world too backward to join the Federation, the facility must be kept secret from all but one of the Earthians: Enoch.

Protected from the ravages of time by his strangely altered home, provided with necessities by his bosses, Enoch enjoyed his first century as stationmaster. Although he had little to do with his human neighbors, he found friends amongst strange beings from the stars, as well as among the ghosts, intangible simulated beings that alien technology could call up for him. Magazine subscriptions helped him stay up to date on human science and his job gave him access to alien ways of thought.

The one sour note in Enoch’s existence is the fact that all of the alien social science he has mastered suggests that nuclear war is inevitable. That’s upsetting but it’s also not something that has to be handled immediately — which is good, because he doesn’t see an obvious solution. The aliens have one — a method to temporarily reduce intelligence on Earth to the point that humans would not be able to operation their lethal nuclear technology — but for obvious reasons Enoch is uncomfortable with that idea1.

Enoch’s quiet life comes apart very suddenly and rather dramatically.

First, the government, as represented by investigator Claude Lewis, suddenly realizes what an anomaly Enoch is. Finding the dead alien buried next to Enoch’s parents only inflames government resolve to find out what’s up at the Wallace place.

Second, when Lewis arranges for the dead alien to be covertly removed from the grave, he does not realize that the aliens will notice when their dead are disturbed. The alien Federation begins to question whether it is worth it to maintain an outpost on such a benighted planet.

Third, Enoch gives sanctuary to deaf-mute Lucy Fisher, something that enrages Lucy’s no-account hillbilly father, Hank.

Fourth, the ghosts who have provided Enoch with much needed companionship suddenly gain enough self-awareness to reject their condition.

And if all that was not bad enough, the alien Federation itself is in crisis. Centuries-long peaceful coexistence is threatened by new divisions between former allies.

Enoch finds himself trapped between undesirable alternatives: leave Earth for the Federation, losing his homeworld in the process, or stay on doomed Earth and lose the stars.

I can’t remember how I discovered Simak. Was it because he was next to Robert Silverberg on the Waterloo Public Library well-stocked shelves? Or did I discover Silverberg because he was next to Simak, leaving the whole question of Simak-discovery open again? It was definitely one or the other. Let this be a lesson to new writers; it’s advantageous to have a surname that places you near an established and popular author2.

So bad things first: it’s been so long since I read this I had completely forgotten that I did not like, and still do not like, the ending. The grand confluence of crises is resolved when an outrageous coincidence allows someone to suddenly demonstrate extraordinary abilities. I will admit there is some foreshadowing but this deus ex machina solution still feels like cheating to me.

My dissatisfaction with the ending is more than compensated for by the rest of the novel, in particular the essentially humanistic approach Simak takes towards the vast and often strange universe in which we live. Other authors might see aliens only as monsters to be annihilated with superscience and rayguns. Simak say them as possible friends.This is one of the essential differences between Simak and many of his contemporaries.

.

Consider the passage wherein the alien first reveals himself:

“Not so idle,” said the stranger. “There are other planets and there are other people. I am one of them.”

“But you …” cried Enoch, then was stricken into silence.

For the stranger’s face had split and began to fall away and beneath it he caught the glimpse of another face that was not a human face.

And even as the false human face sloughed off that other face, a great sheet of lightning went crackling across the sky and the heavy crash of thunder seemed to shake the land and from far off he heard the rushing rain as it charged across the hills.

In other hands, that dramatic moment would have signaled horror. The first description of Ulysses the alien seems to emphasize the eeriness:

It had been a grisly face, graceless and repulsive. The face, Enoch had thought, of a cruel clown. Wondering, even as he thought it, what had put that particular phrase into his head, for clowns were never cruel. But here was one that could be — the colored patchwork of the face, the hard, tight set of jaw, the thin slash of the mouth.

But the passage continues:

Then he saw the eyes and they canceled all the rest. They were large and had a softness and the light of understanding in them, and they reached out to him, as another being might hold out its hands in friendship.

This is typical of Simak’s novels: other beings may seem strange, even horrifying, but there’s always the possibility of companionship for those who can learn to look past the surface. Another author might given us a timid, xenophobic protagonist cowering from the revelation that the universe is filled with eldritch beings and alien ways of thought; Simak gives us a protagonist who would be perfectly happy to sit on his porch next to a Thing from the Stars, the two of them enjoying a pleasant sunset together.

It’s not just the aliens who can be kindly. Lewis is one of the most amiable men in black I’ve encountered in novels or movies. He triggers the crisis not because he is malicious, or likes to exercise power, but because he is curious. Once he understands his mistake, Lewis does his best to set things right as quickly as he can.

The book has a few antagonists: one rascally alien, plus the Fisher clan, who (Lucy aside) exemplify the petty flaws of humans. But even the antagonists are more pathetic than villainous.

I would love to link to a place where you could buy a new copy of Way Station but unless you can buy from this site, I believe you are SOL.

I find the current situation with respect to the availability of Simak’s books in North America quite frustrating. In his day, Simak was a well-known figure. His death in 1988 rated an announcement in the Kitchener Record, a local (to me) newspaper that had never taken much notice of science fiction authors. While it is the typical fate of authors to slide into obscurity after they die, Simak slid faster than one would expect for a widely-liked, award winning author. A decade after his death, I started looking for his books and could only find a few of them still in print. Simak’s literary executor is David W. Wixon. I’d be curious to hear his thoughts on this sorry state of affairs and how it could be corrected.

0: In an odd coincidence, the plot of Avram Davidson and Ward Moore’s 1962 Joyleg is also set into motion by the discovery of a seemingly immortal rustic recluse. The events that follow that revelation are very different from the events of Way Station.

1: Rather disturbingly, it is clear from the text that the dumbification method isn’t something the Federation can apply to an intelligent race but one that they have applied in the past to some unnamed intelligent race.

2: That said, just having a surname starting with S might not be enough to guarantee salience in a truly large collection. The S section of my library is extensive. Just the output of the various Smiths — Clark Ashton, Cordwainer, David Alexander, E. E., Evelyn, L. Neil, Thorne, and so on — occupies a few meters of shelf.