When the Cities Ended

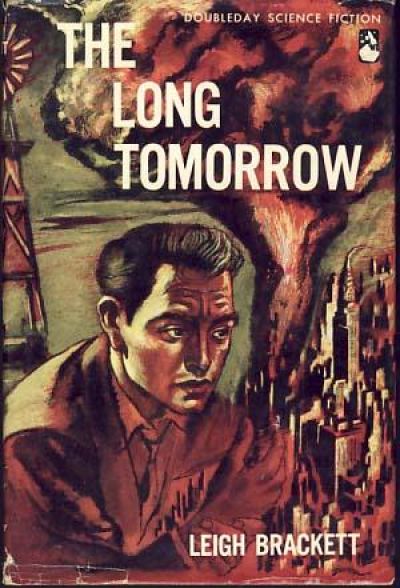

The Long Tomorrow

By Leigh Brackett

26 Oct, 2014

Because My Tears Are Delicious To You

0 comments

The great war between the American-led allies and their enemies killed untold millions as cities burned across the planet. In the aftermath, victorious America resolved that the means to preventing another nuclear war was to prevent great concentrations of people. Accordingly, the 30th Amendment forbids communities of more than a thousand people and limits density to no more than two hundred buildings to the square mile.

Two generations later, the majority of Americans are content to live as Americans did in the 19th century (or at least as they imagine they did) but with one major exception: progress is not just a dead idea, anyone who looks like they might be in favour of progress is subject to disapproval at best and violent reprisal at worst. Although there’s no formal ban that I noticed, advanced technology – as understood in 1955, when this was published – is forbidden, possession enough to warrant death at the hands of a lynch mob.

Raised as a New Mennonite, one of many new hyper-conservative sects in post-War America, 14-year-old Len Coulter has long been intrigued by his grandmother’s stories of the lost Golden Age. Possibly nothing would have come of this had Len’s older cousin Esau not talked him into sneaking off at fair to see forbidden entertainments. The boys see a religious mob turn on Soames, a pleasant man they had met earlier; all it takes to earn a terrible death in this time is the word of one panicky boy.

As it turns out, Soames actually was guilty of dabbling in high technology; Esau, who is much more likely to transgress than Len is, steals a box that belonged to Soames. Inside the box is a radio, something the boys know about from old stories, but their attempts to master it are largely unsuccessful. When their parents learn what the boys have done, Len and Esau are both beaten by their fathers. This is intended to bring the boys back into line but what it actually does is drive both of them from their homes.

The boys’ plan is to head for Bartorstown, a secret community spoken of in whispers, a town where a few people still cling to the idea of progress and humanity’s mastery of nature. What they very quickly discover is tracking down a town that may only exist in rumours and fantasy is trickier than it sounds.

Now men, the pair wash up in Refuge, where they might settled for conventional lives except for two things, alluring Amity Taylor and ambitious Mike Dulinsky. Amity gives Len a sharp lesson what a romantic triangle is like and Dulinsky a reminder that it takes very little to provoke the small minded people of this time o bloody murder.

With Dulinksy dead, Refuge in flames and Judge Taylor’s daughter pregnant, things look pretty bad for the Coulter cousins. Luckily for them, there’s a grain of truth in the stories about Bartorstown and just as the Coulters have long taken an interest in Bartorstown, so Bartorstown has an interest in them.

The reality of Bartorstown is very different from the fantasy Len had in his mind and the more he is exposed to the reality, the more Len is forced to confront his personal limit for the strange, progressive and transgressive.

I got another lesson in how lousy my memory of this is because I had totally forgotten that the book opens with a lynching. Well, a stoning but the result is much the same for its star.

The plot of this had got tangled up in my mind with Andre Norton’s The Stars Are Ours and looking at the publication dates – the Norton in 1954, the Brackett in 1955 – I would not be surprised if Brackett set out to write The Stars Are Ours done correctly. There are a number of parallels but where Norton generally settles for standard pulp-era plot developments — hidden science cities! Superscience! Escape from the Superstitions of Backward Earth! — Brackett plays on pulp expectations only to subvert them over and over. For one thing, generally technologically repressive societies like the one in The Long Tomorrow are the product of some malevolent elite; Long Tomorrow’s are explicitly the product of consensus, made law by duly elected representatives.

The scientists and engineers of Bartorstown may still have nuclear power but they’ve spent two generations chasing a chimera that may not even be possible (although presumably they had reason to think it was back in the beginning). In pursuit of their goal they submit to restrictions on their lives as rigid as any the farmers of America do in pursuit of stasis. I noticed one set of blinkers in particular – Bartorstown’s approach isn’t to try to make it possible to have atomic power without nuclear weapons but rather to make it possible to have nuclear weapons without the widespread destruction of the war. Given that there’s no guarantee that Bartorstown can succeed in their quest and the certainty that some day the current stasis will end, it may be that this is just an early chapter in something like “Letter to a Phoenix” or Canticle, where atomic wars will keep happening until one big enough to end the cycle forever comes along.

There are a lot of books and movies like The Long Tomorrow where the US or part of the US adopts a way of life that would make it easy meat for any external rival and I was pleased to see Brackett actually addresses that issue. All of the USA’s allies went down a similar path after the war and while nobody seems quite sure what the US’s former enemies are doing, they are certain those enemies got hammered even harder than the US during the Destruction; despite the implied carnage overseas, the possibility other nations have their own Bartorstowns gets raised.

One aspect I didn’t care for was the romance but not in an “ew girl cooties” sense. Brackett has a real talent for joyless assignations and romances composed more of grumpy obligation than passion. We can deduce from the fact Amity gets pregnant that sex exists but nobody seems to enjoy anything they do along those lines.

I am not as familiar with Brackett’s fiction as I should be – I have read this, Starmen of Llyrdis, The Big Jump, various Eric John Stark stories and I have seen six of the eighteen movies whose scripts she wrote but I think that is about it – but reading this makes me wonder if I should follow up the 50 Nortons in 50 Weeks with reviews of as many Bracketts as I can track down.

The Long Tomorrow is available from various formats from a variety of publishers