Exhibit A

The Flying Sorcerers

By David Gerrold & Larry Niven

29 May, 2016

David Gerrold and Larry Niven's 1971 standalone novel, The Flying Sorcerers, was Gerrold's first published novel and Niven's fourth. Even though this book uses the vernacular of fantasy, it is a science fiction comedy. More on that last bit later.

Lant may be a humble bonecarver but he is also the only person who can remonstrate with the wizard Shoogar and be heard. This makes Lant his village's primary line of defense against the vagaries of the short-tempered, powerful wizard. Although, as the events that follow the appearance of a rival wizard named As-a-Color-Shade-of-Purple-Gray show, Lant cannot completely prevent Shoogar from throwing destructive temper tantrums.

Purple is curiously ignorant of the ways of the world of the two suns, but the power of his magic cannot be denied. Shoogar could not be expected to tolerate even a weak magician in his territory. Purple's seeming indifference to the wizard’s righteous anger is even more provocative, as is his apparent immunity to Shoogar's magic.

Shoogar is determined to oust his rival. It takes him some time to find a chink in Purple's armour, but he eventually succeeds. Some of the villagers survive the wizard’s revenge. A handful of radiation-blasted survivors find their way to a new homeland, many days travel away from the ruins of their old town.

Shoogar believes that he has completely vanquished Purple. After all, Purple vanished after Shoogar disintegrated Purple’s flying egg (as well as the mountain on which it was perched) in an explosion of light that was brighter than a thousand suns. The natural order is restored and the wizard's war is over.

Except...

Shoogar didn't manage to kill Purple when he sabotaged Purple's flying egg. He marooned Purple on the world of two stars. Worse, Purple ended up in the very same village that offered Lant and his fellow survivors a grudging refuge. Shoogar's only hope to see his rival gone forever will demand from the wizard something unthinkable:

Cooperation.

~oOo~

Someone of questionable notability once said

[Larry] Niven made a name for himself as a hard SF author, which is to say, someone whose SF provides enough technical detail that the reader can be certain that various mechanisms and events couldn’t work the way the author has them working.

For example, if the authors had been a little vaguer about the orbit of the world Purple is visiting, then I would focus on the implied backstory of humans1 living on a planet orbiting two stars, neither of which is a good bet for creating the conditions necessary to a life-bearing world. Instead, the descriptions are specific enough that I must object: “no such thing as stable figure-eight orbits!”

I may have mentioned now and then that I have no sense of humour. The Flying Sorcerers is my exhibit A for this thesis. This book is filled with Tuckerised references to SFnal figures: not only are the two suns are Virn and Oelles (Verne and Wells) but as Wikipedia will cheerfully inform the reader, other figures immortalized as gods include:

- Blok god of violence - Robert Bloch, author of Psycho. [wikipedia note 3→]

- Brad god of the past - Ray Bradbury, for his butterfly effect short story "A Sound of Thunder".

- Caff god of dragons - Anne McCaffrey, known for her Dragonriders of Pern series.

- Eccar the Man - Forrest J. Ackerman, "the man who served the gods so well that he was made a god himself" - a reference to Ackerman's vast involvement with science fiction fandom.

- Elcin god of thunder and lightning - Harlan Ellison, known for a stormy personality, and short stature (the god is described as "tiny"). [wikipedia note 2→]

- Filfo-mar god of rivers - Philip José Farmer, known for his Riverworld series. [wikipedia note 2→]

- Fineline god of engineers - Robert A. Heinlein.

- Fol god of distortion - Frederik Pohl; a teasing allusion to his extensive work as an editor.

- Furman god of "fasf" - Edward L. Ferman, long-time editor of The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction (often abbreviated as "F&SF").

- Hitch god of birds - Alfred Hitchcock, directed The Birds. [wikipedia note 3→]

- Klarther god of the skies & seas - Arthur C. Clarke, who wrote many works dealing with space travel ("skies") and oceanic adventures ("seas")

- Kronk god of the future - Groff Conklin, who edited forty science fiction anthologies.

- Leeb god of magic - Fritz Leiber, for his sword-and-sorcery stories.

- Musk-Watz wind god - Sam Moskowitz, known for his loud voice and long speeches. [wikipedia note 4→]

- Rotn'bair god of sheep - Gene Roddenberry, creator of Star Trek.

- Lant mentions that Rotn'bair's sign is the horned box, i.e., a TV set with rabbit-ears antenna on top.

- Nils'n god of mud creatures - Nielsen ratings, arch-enemy of Rotn'bair (Star Trek had poor ratings).

- Lant explains that the sign of Nils'n is a diagonal slash with an empty circle on either side, i.e. "%".

- N'veen god of tides & map makers - Larry Niven wrote about tides in "Neutron Star" and maps in Ringworld.

- Pull'nissen god of duels - Poul Anderson, a founding member of the Society for Creative Anachronism; he was a Knight of the SCA, therefore skilled in one-on-one combat.

- Po god of decay - Edgar Allan Poe, for his morbid stories.

- Sp'nee ruler of slime - Norman Spinrad, for his controversial writing, and his giving of irritation and offense to many.

- Tis'turzhin god of love - Theodore Sturgeon, who wrote many stories about variations of love and sex.

- Tukker god of names - Wilson "Bob" Tucker, who playfully used names of friends as some of the character names in his fiction.

- Yake god of what-if - Ejler Jakobsson, the penultimate editor of If magazine.

Even though I knew who most of the people were, I missed all of that. [Editor’s note: so did I.] I did notice that the two bicycle-makers-turned aeronauts were named Wilville and Orbur but it didn't occur to me that any of this was intended as comedy until I got to the revelation (pages 261 and 262) that Purple's real name was ... actually, I’d better not spoil it for you. Given that I think was exactly the audience at which the authors were aiming their comedy (a just-turned-sixteen-year-old male nerd), my failure to notice that this was comedy suggests either failure on their part (unlikely, since this book was popular) or on mine. At least I noticed the humour inherent in the fact that Shoogar insists in interpreting everything in terms of magic, when the novel is very clearly about a spaceman marooned on an alien world.

On this rereading, I found myself focusing on the book's astoundingly horrible treatment of women. I admit that I am not surprised when I discover that an old Niven novel is egregiously sexist, but I expect more of David Gerrold.

Lant’s culture is one that would require far-reaching reforms if women were ever to reach even second class status. Much of the intended humour of the book (IMHO) comes at the expense of Lant’s (and his fellow men’s) horrified reaction to Purple's casual acceptance of woman as people. Purple gives them individual names (!!!) and non-traditional jobs. However, there is no evidence in the book that Purple is particularly bothered when women are treated as brain-damaged chattels; he names the women because he cannot otherwise keep them straight and he drafts them into the labour pool because he is short-handed. It's a sad thing that the march of time and evolution of mores can rob one of the ability to laugh at simple domestic abuse.

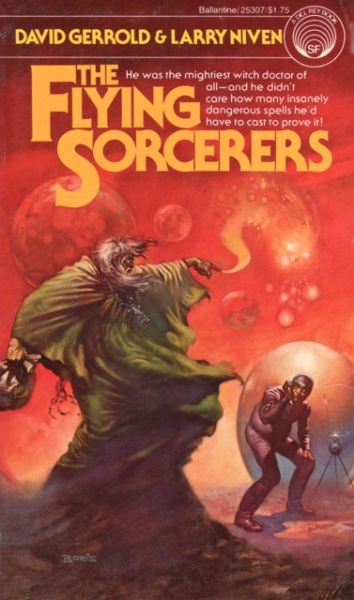

The 1971 edition had this Di Fate cover:

I opted for the 1977 Boris Vallejo cover for a couple of reasons. One is because it's the cover on my copy of the book, the cover I associate with this story. Another is because even though Vallejo takes some liberties with the appearance of the characters, his cover conveys the basic science-versus-magic tone of the novel more effectively than the Di Fate. I have even convinced myself the artist's depiction of Purple resembles the real-world figure on whom Purple is based. Other people must agree with me, because later editions from other publishers reused the cover art.

The book may be obtained here or from the used-book emporium of your choice.

- The locals may be furry all over, but Purple fathers a child on one so they are Homo sapiens.

- I am still learning how to insert the Amazon links so there is an implied "when it appears".