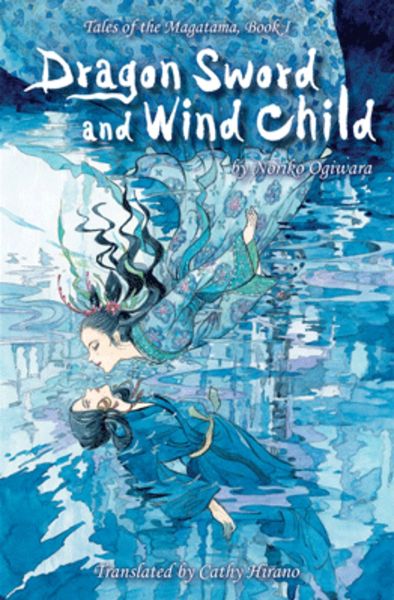

Haikasoru 5: Dragon Sword and Wind Child/Tales of the Magatama, Book I by Noriko Ogiwara (Trans. Cathy Hirano)

Dragon Sword and Wind Child (Tales of the Magatama, book 1)

By Noriko Ogiwara (Translated by Cathy Hirano)

26 May, 2011

0 comments

Dragon Sword and Wind Child/Tales of the Magatama, Book I

Noriko Ogiwara (Trans. Cathy Hirano)

VIZ/Haikasoru

$13.99 USA / $18.99 CAN / £8.99

352 pages

ISBN: 978−1−4215−3763−4

I don’t know why but recently I’ve been encountering fantasies where the existence of marriage counselling services would have avoided a lot of bloodshed and misery all round.

The God of Light and the Goddess of Darkness were a loving couple, co-creating the world and all the gods in it until the birth of the God of Fire; horrified at his wife’s injuries after the delivery of the incendiary deity, the God of Light killed the Fire God, then sealed his wife away in the Underworld. The two Gods have not spoken directly ever since.

The God of Light governs celestial affairs, preferring the perfect and unchanging over all else. The Goddess of Darkness is an earth goddess, comfortable with the processes of death and rebirth. Their creations reflect this; humans die and are reborn. The God of Light’s children, Prince of Light Tsukishiro and Princess of Light Teruhi are eternal, immortal, unchanging and inflexible; the ability to change would imply that they were in some way flawed, an abhorrent concept.

The God of Light has a grand plan to fix everything that is wrong with the world, to return it to a perfect state. Step one involves getting the kids to conquer the known world, a land called Toyoashihara, bring all the humans under the control of the God of light (or kill the ones who refuse), subjugate and bind the lesser gods and generally get things ready for restoration back to the initial state. This will as a side effect probably kill every mortal thing in the world but this is a cost the God of Light is willing to pay. So are a surprisingly large number of mortals.

Saya is an orphan girl, the lone survivor of a Darkness community wiped out by the forces of Light. Found wandering in the woods, she was adopted by the people of a community loyal to Light. Shortly after she learns from a group of people working for Darkness that she is the reincarnation of the Water Maiden Sayura, she encounters Prince Tsukishiro. He immediately decides that she is to become his new handmaiden. In this world, it is never a good thing for the little people to come to the attention of nobility; Saya’s first reward for catching the prince’s eye is that a jealous shrine maiden tries to murder Saya. After that, things get worse.

Saya isn’t the first reincarnation of Sayura to encounter the prince and every single previous version of her lived a very short life after the prince found her. Tsukishiro’s perpetually angry sister Teruhi is not impressed by her brother’s attraction to doomed Water Maidens and a large part of this seems to be because the pair are simultaneously inseparable and incapable of tolerating the other’s presence for any amount of time. Another factor is that the Water Maidens are of the Darkness and Teruhi rightly thinks letting an endless sequence of the same enemy agent inside the palace defenses could backfire [1].

In fairly short order, Saya is placed in an untenable position and as luck has it this coincides with her becoming aware of a resource within the palace that the Prince and Princess would prefer nobody knows about. It seems there is another child of the Light God, Chihaya, one the others have been careful to keep secret as means of controlling Chihaya. Chihaya has the invaluable talent of being able to wield the Dragon Sword; forged from the rage of the Fire God, it is the only known weapon that can kill Children of Light and even the God of Light himself (One of the abilities the Water Maiden has is to still the Dragon Sword, something that doesn’t endear the Maiden to Teruhi). When Saya is forced to flee, she takes Chihaya with her.

At this point the next complication arises: Chihaya is not averse to helping the humans but he’s immature, deliberately kept poorly socialized even for a god, and learning is not something that comes naturally to Children of Light. Combined with the facts that he is effectively a walking nuclear weapon given to fits of pique and his mere presence enrages the minor godlings that Darkness seeks to free and you can see he’s not the safest ally the Darkness could have.

This novel was first published in 1988. The notes in the back indicate that Ogiwara was inspired by Western fantasies that she read in translation; in particular she was inspired to use the Kojiki (an ancient body of significant tales) in the same way Western authors incorporate Celtic myths. Of course, while I have read roughly infinity Celtic flavoured fantasies, the same is not true of stories based on the Kojiki.

Someone online in a review I read suggested that Light and Dark were suboptimal choices for the names of the two factions and that Sky and Earth might have been better. I’ll disagree; the forces of Light really do think they are doing what’s best of the world and Darkness is evil.

The description of the little gods is reminiscent of the gods in Princess Mononoke (unsurprising, as I expect the authors are drawing on the same source material); they are both necessary for the proper functioning of the world and extremely dangerous for humans to be around. In fact, if any of the godlings are able to be reasoned with, I don’t think we see that. They act more like they are mindless or at best, animalistic; forces of nature (duh) rather than people.

It’s good that the focus is on the humans (or on a god trying to learn human virtues) because none of the higher-level gods come off all that well. In fact, I will go a bit farther and say the God of Light is a dumbass with no sense of proportion and his former lover, while subjected to outrageous and unacceptable provocation, perhaps could work on her communication skills. The Children of Light are what their father made of them but as the youngest showed, they are actually able to learn if they want to; for the most part they refuse even when it is clear their actions continually bring them pain. I can see no general lesson in this.

It’s a shame that the scenes with the lesser gods makes it clear the gods are needed for the proper functioning of the universe, because otherwise I’d advise a round of pro-active atheism (instead of “there are no gods”, “there will be no gods”). Sadly, that’s not a solution that can work in this universe.

Fans of feudal systems will be interested to note that in this universe, the powers-that-be are generally very keen on the details of what the little people owe them while deferring concern about what they owe the little people.

Many of the elements of the story are conventional but used with considerable skill; I can point to likely inspirations but the work is not derivative of them [2]. it’s clear why of all the books that must have been available for translation, this one was selected.

1: When the book made it clear what the sequence of dead Water Maidens was working towards, I was reminded of Budrys’ Rogue Moon.…

2: Interestingly, there are a lot of parallels with The Hundred Thousand Kingdoms, another example of authors coming up with comparable ideas 20 years and thousands of kilometers apart…