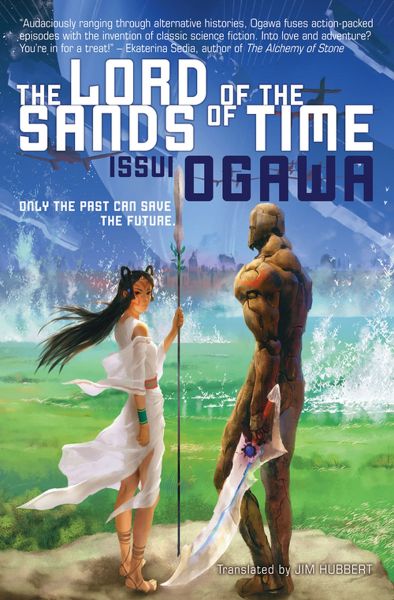

Haikasoru 7: The Lord of the Sands of Time by Issui Ogawa (Trans. Jim Hubbert)

By Issui Ogawa (Translated by Jim Hubbert)

1 Jun, 2011

0 comments

The Lord of the Sands of Time

Issui Ogawa (Trans. Jim Hubbert)

Haikasoru/VIZ Media LLC

196 pages

SRP: $13.99 USA/$18.99 CAN/£8.99

ISBN 9781421527626

The Canadian pricing on this seems … daring.

Some spoilers will follow.

A reader flipping through the early pages of this book could be forgiven for thinking this is a secondary world fantasy; Lady Miyo, out for a ride with her faithful slave Kan, encounters a mononoke, a demon of sorts, and survives thanks to the timely intervention by warrior in blackened, cracked armor, bearing a talking sword. There are hints that this isn’t the case: there’s a date, 248 AD, which ties it to the history of our world and the warrior and his sword do not speak in a way one might expect a warrior of the Yayoi period to speak but more like a pilot talking to their wingman.

There a number of hints early on that while this may be a 248 AD, it is not our 248 AD:

Lady Miyo knows not just of China (whose records of this era are, I think, among the earliest accounts of what became Japan) but she also knows about Rome and about a land over the ocean called Kentak by its red-skinned inhabitants. All the world is united by the same set of Laws, handed down from time immemorial, and while this hasn’t prevented the usual sort of human political games, from coups to wars, it does mean humans all come with a cultural package strongly encouraging them to unite in the face of overwhelming calamity. This is good because there are a lot of mononoke and more coming, and the one thing the mononoke want to accomplish is the extermination of humanity.

The mysterious warrior is Messenger O, an android created in 2598 in a solar system where humans had lost the battle for the inner solar system to alien invaders (ET, which stands variously for extraterrestrials, Enemies of Terra and finally Evil Things); humans seemed to be holding their own in the outer system due to the enemy’s reliance on solar power. Unfortunately, the existence of time machines and the lack of allies flooding in from the future suggests that humans do not have a future from which allies could flood. Equally unfortunately, the existence of time machines means the aliens can escape the current stalemate by heading into the past where humans are less developed and more easily defeated. Poor O barely has time for a doomed romance with a prickly supply officer before he joins his kind and is launched into what will prove to be an extremely protracted war spanning hundreds of thousands of years in hundreds of time lines.

The logistical bases of both sides shrink as they continue their wars back thought time, armed with an ever-decreasing arsenal as they probe deeper into the past; for the messengers this means greater reliance on their flawed and fallible human allies. To make things worse (presumably for both sides but we only see the Messenger point of view), history is some extent overwritten in the time wars, although there seems to be a strong tendency for history to be conserved; entities whose creation in the future is prevented by some event in the past simply vanish.

Most of the book involves the grand struggle in 248 AD but there are brief scenes in the 22nd century and the 20th, as well as a reference to the 19th. Ogawa only has two hundred pages to with, so he cannot waste a lot of time and space. To quote Sean O’Hara:

[…] Lord of the Sands of Time is quite long; it just uses a highly efficient compression algorithm. The story contains the entire plot of Turtledove’s World War series compressed to five pages, and Guns of the South as a one paragraph flashback.

Turtledove isn’t the only Western author who could benefit from contemplation of Ogawa’s book and a harshly enforced page limit on his novels but he’s certainly the first one who comes to mind.

I have Ogawa classified as a sort of Japanese Poul Anderson1, which would make this his Manse Everard book; part of this is might because while Ogawa certainly doesn’t have an issue with women in positions of authority, the stories I have seen by him are very accepting of conventional power structures and conventional relationships, whatever the convention for the particular era is. O is comfortable with lover2 Sayaka having a job but at the same time he’s comfortable with the idea of allying with Nazis3 and with American slavers4. Part of this is because the greater goal of human survival trumps all other concerns and part is because a time traveler by necessity has to be somewhat dispassionate about the peoples of the past, who are all doomed phantoms, but Ogawa gives the impression that while he isn’t opposed to egalitarian social structures, he’s also not particularly interested in them.

The model of time travel used in this seemed inconsistent; one time line makes sense to me and an infinity of branching time lines would as well. Four hundred timelines are just peculiar.

I also want to poke the ETs with a stick over the reason they went to war with humanity: human exploration of a world orbiting Teegarden’s Star, a nearby red dwarf, has the side effect of causing a mass extinction worse than our Permian and in the view of the aliens, delayed their appearance by millions of years. Granted, there’s what seems to be a linguistic problem here: there are times when O uses “human” where a more general “people” should have been used and the AI relaying the ET complaint means that the appearance of intelligence was delayed by millions of years. Still, this is like complaining that the Permian/Triassic extinction delayed the appearance of humanity by a hundred million years thanks to the archosaur digression.

Page 127 goes into the model used:

“Because if the damage they inflict takes place too far in the past, it won’t influence the human species. Biological evolution is highly adaptive. Given enough time, even the effects of extensive damage can be overcome. Of course, the new evolutionary path may yield humans that are not primates or even mammals. But the concept of parallel evolution should apply across branching time lines.”

Granted, this is an AI talking to an android and their definition of human may be very flexible (although not enough to encompass what’s behind the ETs) but it all smacks of orthogenesis.

Despite my reservations, I enjoyed this book; I might question the basic models used at least it was the sort of book where there’s a point to having reservations, rather than being some piece of disposable trash on which consideration is utterly wasted. Within the boundaries of its assumptions, the novel functions quite well and despite the fact that it covers 100,000 years in 200 pages (or about a year or two per word), it’s a lot less episodic and more of a smooth whole than one might expect. It doesn’t quite scratch the same itch for me the other Ogawa did but it’s certainly enough to keep me looking for more Ogawa novels.

1: Although Anderson never did a space development story as detailed as The Next Continent.

2: O pines for Sayaka for a thousand centuries. Take that, Mary O’Meara!

3: The Messengers do insist that Auschwitz be shut down but it’s quite possible that this is not on humanitarian grounds but because the logistical demands of the Nazis genocidal programs are undermining the war effort.

4: The description of the American Civil War may raise the odd eyebrow. Page 136 ‑137, O tries to explain the American Civil War to a woman who literally cannot imagine a society without slavery:

“At that time, Kentak was part of a country called America, where the white-skinned peoples had taken over from the red-skinned tribes. The country was divided into whites who held the black-skinned slaves by force, and other whites who were opposed to slavery.”

“They wanted to kill the slaves?” asked Miyo.

“Kill them? No, they wanted to free them.”

“Then what? Would they abandon them?”

“They assumed the slaves would fend for themselves,” replied the Messenger.

“How heartless,” said Miyo. “Slaves would die without their masters.”

“People of the North thought it would be better for the slaves to die than to be worked like beasts”.

And a few paragraphs later O mentions sending the slaves to fight the ETs, who massacred them and their white allies in huge numbers.