To the people who voted for Brexit, a love letter

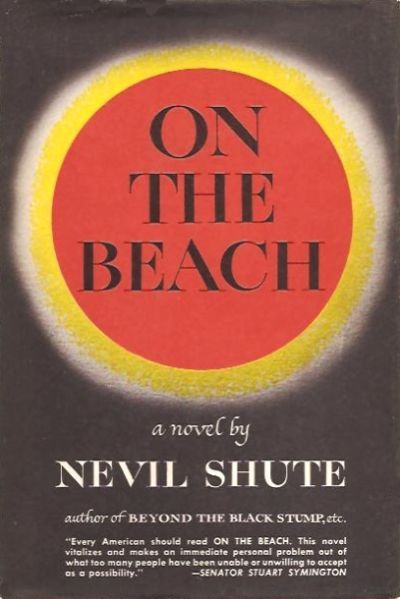

On The Beach

By Nevil Shute

3 Jul, 2016

Because My Tears Are Delicious To You

0 comments

What better work to celebrate Brexit’s victory than Nevil Shute’s 1957 ode to the power of collective determination, On the Beach?

In 1963, the world is at peace. No wars, no riots, no arguments mar the calm in the Northern Hemisphere. This is because many of the 4700 nuclear weapons detonated during the thirty-seven day war that broke out in 1962 were cobalt-clad. Bathed in lethal radioisotopes, the Northern Hemisphere is innocent of life and all its complications.

In Australian and the other nations of the Southern Hemisphere, life continues. But only for the moment: lethal fallout is slowly but inexorably spreading on the winds. Even as the book opens, northern Australia has been cleansed of life. By September 1963, everyone — everything — in southern Australia will as dead as the unfortunates in the north.

This is the way the world ends

Not with a bang but a whimper.

Of course, every person who has ever lived was as doomed as the people in Melbourne. The only difference is that the doomed people of Earth have a rough idea when they will die … and they also know that nobody and nothing will follow them. There’s the better part of a year to go before the end, time that can be used productively.

And perhaps things are not quite as grim as they appear. Scientist Jorgensen believes fallout is being scoured from the winds faster than is believed. Australia is receiving intermittent radio signals from Seattle. If someone managed to survive the hellish radioactivity blanketing the US, perhaps there is hope for Australians and the other people of the southern hemisphere.

The USS Scorpion survived the war. Its atomic motors give it the range to reach and return from America, to see if somehow life survives there, and to carry the news back to Melbourne. Along the way it can carry out tests to see if Jorgensen is indeed correct. Commanded by Dwight Towers, and crewed primarily by American sailors, the submarine will also carry two Australians seconded to the vessel: Lieutenant Commander Peter Holmes and Professor John Osborne.

And if hope is not rewarded? Dwight, Peter and John will return to an Australia even now preparing for fallout the only way it can: by providing means for its doomed population to end their lives as peacefully, as painlessly as possible.

~oOo~

Shute’s world has a few significant assumptions that drive the plot. First is that nuclear weapons were astoundingly cheap, thousands of dollars a pop. The second is that the great powers (for some odd reason) thought that generously handing out nuclear weapons and the means to deliver them over great distances was a good idea1. While the great powers certainly made a significant contribution to the later phase of the war, the first shots were fired by Albania and Egypt. In the confusion of Egypt’s attack on the UK and the US, America misread the significance of Egypt’s second-hand Soviet aircraft and the war escalated from there.

Shute’s model of how fallout spreads is more dramatic than realistic.

What stands out about the novel is the utter absence of Hobbesian conflict. This is not Mad Max’s Australia. Gardeners plant seeds they will never see bloom. One group is constructing a durable record of humanity for the benefit of any intelligent beings that might evolve in Earth’s distant future. Even the government does the best it can under the circumstances: the suicide tablets are free2.

The general acceptance of impeding, inevitable death may seem odd, but while the situation is new to the reader, the characters had had a year to come to terms with their situation. Some, like Dwight, find meaning by embracing struggle despite its inevitable end:

“You call finding out the bad things fun?”

“Yes, I do,” he said firmly. “Some games are fun even when you lose. Even when you know you’re going to lose before you start. It’s fun just playing them.”

Peter’s Mary ignores the inevitable as long as she can. Moira Davidson, whose romantic ambitions regarding Dwight are as doomed as humanity (because her rival is a dead woman with whose memory Moira cannot compete), finds a middle ground; she accepts her impending death while drinking herself into emotional numbness.

And perhaps there are ways to look at the situation that are not utterly horrible. Londoners concerned about the economic implosion coming once London-based financial organizations move out of the UK to more EU-friendly locations might take comfort in this:

Maybe it’s all still there, just as it was, with the sun shining down the street the way you’d want to see it. That’s the way I like to think of that sort of place. It’s just that people don’t live there anymore.

Perhaps that’s London’s post-Brexit future. There will still be a London. It’s just that people won’t live there any more.

On the Beach can be purchased here.

1: In real life, the US did provide nuclear weapons to other countries, weapons that were under the nominal control of the host nations. The US did insist that the security on the foreign nuclear weapon facilities be at least as good as the security at American facilities. With one exception: rather than offend Quebec by delaying the opening of the Quebec nuclear facility until it could be brought up to code, the US waived the requirement. This was a perfectly sensible decision. No reasonable person could object to an increased chance that nuclear weapons could be accidentally or deliberately misused if it meant pacifying the Quebecois.

2: Nobody seems to be building a radiation-proof facility to wait out the deadly years or if they are, they are polite enough not to rub the noses of their doomed neighbors in the fact.