A Tale of the Commons, Part One

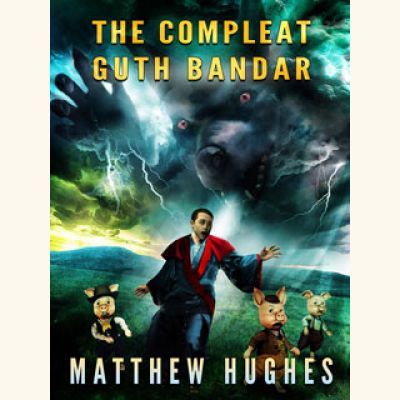

The Compleat Guth Bandar (Commons, volume 1)

By Matthew Hughes

24 Feb, 2015

0 comments

This week I planned a Rediscovery review of Black Brillion, a novel by self-confessed Canadian Matthew Hughes.You may notice that this is not a review of Black Brillion after all, but a review of The Compleat Guth Bandar.

This is because when I contacted Hughes, he said (in part)

I’m very happy to have you review the book, but if you do could you also include reference to the Guth Bandar stories? They were fixed-up into a companion novel called The Commons, which has no ebook, but I published the stories last year as The Compleat Guth Bandar. I’ll send you the ebook, and I think you’ll find it’s not more than one per cent different from the fix-up. Together, the collection and BB make one big story.

The reason for that is: the story I conceived of for Black Brillion was too large to fit the wordage limit Tor would allow me. So I trimmed and, judging from some of the reviews, left too much for the reader to figure out. To remedy that failing, I turned the missing elements of the narrative into a series of stories featuring Guth Bandar, explorer of the collective unconscious, and sold them one by one to Gordon Van Gelder. I was essentially writing a novel in episodes with the intent of selling it complete to a publisher, which eventually I did — to Rob Sawyer.

But to understand the full story, you’d need to read both.

So, today (headache permitting) you will get two, count them, TWO reviews: this one and one of Black Brillion.

Introduction

This essay covers much the same publication history recounted in the email. Tor contacted Hughes to write a novel set in the same Archonate as his earlier novels, 1994’s Fools Errant and 2001’s Fool Me Twice [1]. Unfortunately, Tor was very firm about word count limits on the novel in question, Black Brillion, and so a considerable portion of the book had to be left out. This material became the Guth Bandar stories.

I haven’t put David Hartwell, Hughes’ editor at Tor, to the question, but I believe I have a good idea about what was going on behind the scenes. As I recall, in the summer of 2003, the big bookstore chains, Barnes and Noble, and Borders — remember Borders? They sold books. Well, they tried to sell books — told publishers that mid-list SF hardcovers over about 100,000 words (I think) didn’t sell in sufficient numbers. Neither B&N nor Borders would carry long mid-list SF any longer. Books already in the pipeline were subjected to various unavoidable adaptive measures (if you noticed a flurry of duologies back then, this was why) and of course upcoming books would have been subject to draconian length restrictions.

It may be that there are authors reading this review who were affected by the length restrictions and it might even be that they will want to complain at length about them in comments. Certainly this paragraph is not intended as encouragement or incitement for profanity-laced commentary.

But first! some words about the background of the stories: protagonist Guth Bandar lives a very long time in the future, in the Penultimate Age of Old Earth, so long from now that our garbage dumps have been crushed and transformed into new materials. Old Earth is very very old and as far as most of the inhabitants, human and otherwise, are concerned, everything that can be done has been done. Attempts at novelty are not just misguided; they are in bad taste.

The Institute of Historical Inquiry explores the Commons, what we would call the collective unconscious of humanity. For us it is a conjecture; for the Institute it is a realm they can visit at will, a world filled with the accumulated memory of humanity, our most fundamental archetypes, and, of course, danger.

“A Herd of Opportunity”

Young Institute of Historical Inquiry scholar Guth Bandar accompanies his mentor Preceptor Huffley to the distant world of Gamza. Huffley has promised the Eminence Malabar that Huffley can remove the excrescence of a town devoted to entertainment and commercial debauchery from the Eminence’s doorstep. In fact, Huffley is on Gamza to study the alien (and telepathic) Bololos, who seem to have been affected by the proximity of humans in an unexpected and interesting way. Since a scholar like Huffley couldn’t possibly afford to pay his own passage to Gamza, he has resorted to claims of dubious factuality to convince the Eminence to pay Huffley and Guth’s way.

While defrauding a fanatical religious cult is the sort of endeavor that can only end happily, the possible joy that promises is as nothing compared to the experiences one might have stumbling into an alien Commons whose basic rules one does not understand.

I have to say that while Guth sometimes appears a little timid, he accepts as part of his vocation some extreme risks. Even the well-documented human Commons is filled with phenomena and personages who could very easily kill scholars like Guth (or do worse than kill). Yet not only do Guth and his fellows return to the Commons again and again, Guth ventures beyond it.

“A Little Learning”

Wending his way through a dreamscape as part of an Institute exercise, Guth discovers that his loathsome rival Didrick Gabbris has sabotaged a crucial element Guth needs to traverse the dream world. Seeing no other choice, Guth improvises a new route to reach his goal, showing in the process why the Institute frowns on innovation.

Poor Guth seems to have a talent for finding ways to inspire the Institute to distance itself from him. Institutional disapproval doesn’t seem to stick — at least not the first few times.

This story drew my attention to something I had not previously noticed, which is that women in the Archonate stories I have read tend to be supporting characters at best and quite often, as in this story, some combination of reward and menace. Granted, the women Guth encounters in the Commons are not people but archetypes but, having spotted the pattern, I kept noticing it.

“Inner Huff”

Another foray into the Commons, this time in search of what Guth hopes will be the first new archetype to be recognized in a very long time. The key to successful research is not to get so caught up in it that one is noticed and transformed by the local analog of Circe. If you are careless enough to fail at that, at least try not to be drawn into a succession of pig-related Events from the fairy-tale side of the Collective Unconscious. Guth fails at each juncture, but he does at least manage not only to survive, but to emerge with the basic elements of a remarkable and unprecedented discovery that should, if the universe is at all just, both establish Guth as a great scholar while crushing his bitter rival Didrick Gabbris!

“Help Wonted”

Following his ejection amid jeers and calumnies from the Grand Colloquium of the Institute of Historical Inquiry, Guth enters the Commons once more in search of proof of his thesis: the Commons has become self-aware. Unfortunately for Guth, not only is he correct but the Commons has taken a close interest in Guth. While Guth may reject the role chosen for him, the Commons is more determined than Guth can possibly know.

“Bye The Rules”

Having abandoned the scholarly life to assist his uncle Fley at Fley’s Merchantile Emporium, Guth is alarmed and outraged to discover that some underhanded scoundrel is plotting to undermine Fley’s business. Worse yet, the scoundrel is none other than Guth’s bitter rival Didrick Gabbris!

Once again, Guth finds himself drawn into the Commons. Even if he and his uncle survive what waits for them there, the foray offers the Multifacet, the personification of the Commons, one more chance to shape Guth to its own ends.

“The Helper and his Hero”

Decades after being forever banned from IHI for his supposed role in driving bitter rival Didrick Gabbris insane, Guth sees the opportunity for redemption in a bold act of research. Poor Guth never learns from experience. Key to his research is a foray into Old Earth’s barren Swept, the relic of an alien invasion long ago defeated. There he will meet a young aristocrat who is traveling under the name Wasselthorpe. The determined young aristocrat is both less than he appears and a being of alarming potential. The more Guth comprehends with whom and what his fate has become inextricably connected, the more Guth is alarmed.

Unfortunately for Guth, all his frantic efforts do not allow him to escape the role the Multifacet has chosen for him. Stepping into that role may mean Guth’s death (or worse), but rejecting it could doom Old Earth itself.

Poor Guth. I would mock him for not learning from experience — how often does he nearly die in the Commons? How often do his bold stratagems end with humiliation? — but he’s the chosen tool of beings far more ancient and far more cunning than he is. Among the Multifacet’s many abilities is the altering of memories. Guth doesn’t learn because he is not permitted to learn.

However, he is doing better in this regard than the supposed “Wasselthorpe,” who has been shaped to a greater degree and with even less concern for his long term well being than has Guth.

***

Unsurprisingly, because Guth was intended to be a major character in Black Brillion and because Black Brillion was the first Hughes book I ever read, this collection was very close to my internal model of what a Hughes book should be like: a rather naïve protagonist, who lacks the self-awareness to understand just how out of his depth he is, applies his genuine talent and knowledge to the pursuit of a series of humiliating (although entertaining for the reader) learning experiences.

Hughes is often compared to Jack Vance. The Penultimate Age of Old Earth seems to be leading into the world of the Dying Earth, when Magic has replaced Science. While I can see the similarities and the moments of homage, I didn’t actually read much of Vance until after I’d begun reading Hughes [2]. Vance is not part of my SF background the way he is for other SF readers. From this admittedly odd perspective, what I see is a crucial difference between Hughes and Vance: Hughes strikes me as more humane than Vance, who often seems misanthropic; Hughes does terrible things to his characters but with an undercurrent of sympathy. The protagonists may spent their lives living through absurd situations but then, don’t we all?

The Compleat Guth Bandar and other Matthew Hughes books can be purchased here.

1: Which the Science Fiction Book Club omnibused in 2001 as Gullible’s Travels.

2: In my defense, the handful of Vances I read in the 1970s were apparently among his worst books.