A thrilling colonialist adventure

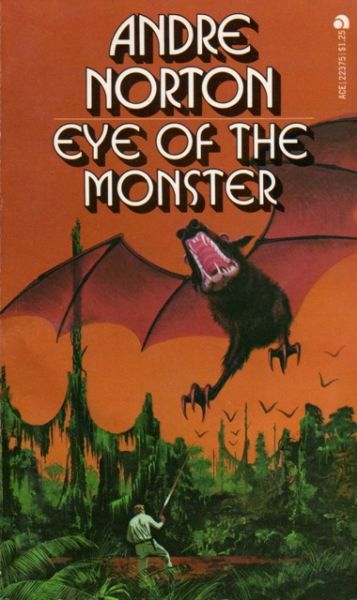

Eye of the Monster

By Andre Norton

8 May, 2015

0 comments

I learned a couple of useful lessons reading 1962’s Eye of the Monster. One was that, contrary to my belief that the Number 24 bus loops back to Westmount and Highland in ten minutes, it actually takes long enough for me to read a considerable fraction of a short — 135 pages in the 1984 Ace MMPK — novel like Eye of the Monster [1]. The other lesson was that Norton could write books that reminded me of Jack Vance’s novels, but not in a good way.

The planet Ishkur! Once part of the South Sector Empire but now, thanks to the whim of the Imperial Council, on the verge of independence. The native Crocs have promised toleration to such of their former colonial masters as remain on Ishkur, but this is merely a ruse. Inexplicably, the rank-smelling natives have no love for their former colonial overlords, even though Imperial ways “were better than the rule the natives had for themselves.” The only peace the off-worlders will be granted is the peace of the grave!

Unlike his wooly-minded uncle, Rees Naper has no illusions about how far to trust the savages’ word. Orphaned son of a Survey officer, Rees has been trained since birth to survive on alien worlds. Dragged out of cadet school by his uncle following the death of his father, Rees can sense that things are about to go pear-shaped on Ishkur. Alas, his attempts to convince his uncle or any of the other adults of what is to come fall on deaf ears.

By very good luck, Rees is commuting to his job when the native uprising finally explodes. This means he isn’t at his uncle’s Mission when the Crocs overwhelm and massacre most of its inhabitants He also manages to miss out on the spot of torture that happens at his job site (although a beloved pet is not so lucky).

Even on his own, Rees would have had a tough time evading the Crocs and making his way to safety. Unfortunately he finds himself saddled with Gordy, an empty-headed young boy who occasionally pipes up with anti-colonialist platitudes. Rees’ task is further complicated when he and Gordy stumble across Zannah, a Salariki child. Because there is no situation that cannot be made worse, Zannah soon wanders off and is poisoned by a Croc trap.

The one bright note is that the party is joined by a Salariki adult [2], a female named Isiga. Shepherding two helpless children to safety through a predator-filled jungle will not be easy, but with Isiga’s help, it becomes barely possible.

Pity that the Crocs are swarming through the jungle. Even more regrettable is the fact that the primitives have somehow got their reptilian claws on modern weaponry…

~oOo~

This is basically a padded-out novella. Norton didn’t have much space to work in here. The natives aren’t really fleshed out beyond being violent, smelly, brutal, backward (except for weapons stolen from their betters), untrustworthy, and totally ungrateful for the Empire’s efforts to civilize them. The plot is padded-out as well: it’s basically a desperate race to escape the natives.

Gordy and Zannah exist mostly to be the Loads. Although Zannah is the first one to wander into danger, Gordy’s uncritical acceptance of the adults’ assurance that the Ishkurians (“Croc” is a word of which he disapproves; he calls it a “degrade name”) are trustworthy makes him just as incapable of avoiding danger. It’s a credit to Rees that he doesn’t just punt the pair of them into the first pit-trap and leg it out of the region on his own.

Mind you, Rees also parrots what he has heard from adults. It’s just that Survey views natives like the Crocs with considerable disdain and distrust. On Ishkur, those views will keep humans alive longer.

Although Norton’s prose was never as flashy as Jack Vance’s, this book does remind me a bit of Vance’s The Grey Prince, which was Vance’s grumpy reaction to events in Rhodesia in the 1970s. This Norton is a straight-forward piece of pro-colonialist fiction, a reaction to the on-going collapse of European colonial empires following WWII. It reads badly now, but it would have appealed to a significant chunk of Norton’s readership when published. Yet …

it seems inconsistent with the pro-native slants in other Norton works published around the same time, so I am left baffled as to why she wrote this oddity.

1: Bus neep: my error was assuming that just because an inbound Route 24 bus shows up ten minutes after the outbound 24 drops me off at my destination, it should only takes ten minutes for the outbound bus to loop back around. In fact, the inbound 24 bus that shows up ten minutes after the outbound is the bus that left the terminal a half-hour before the outbound 24 I ride out on. The loop takes significantly longer than ten minutes. How much longer is left as an exercise for the reader.

Why did I take the outbound bus rather than my usual inbound? Road construction; location of inbound bus stop unclear; bus might not stop if I were waiting at the wrong place.

I don’t know why my exgf calls me the bus-whisperer. It’s not like I am obsessed with the routes I don’t use regularly.

2: According to ISFDB, this book is set in the same sequence as The Sioux Spaceman. I think they are wrong. The Salariki are mentioned in the Solar Queen stories, which I don’t think can be shoehorned into The Sioux Spaceman’s timeline.