Better to break than to bend

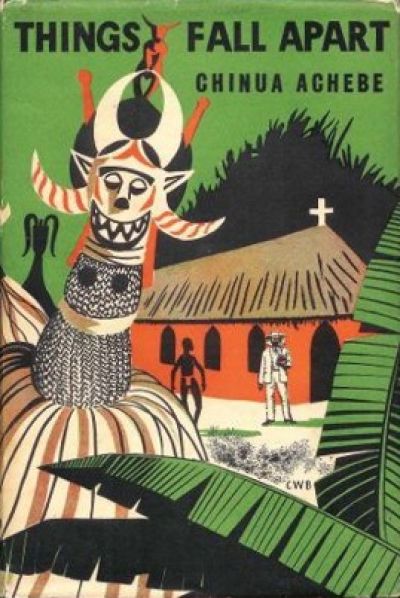

Things Fall Apart

By Chinua Achebe

21 Feb, 2016

Because My Tears Are Delicious To You

0 comments

Chinua Achebe’s 1959 novel Things Fall Apart can teach us many things. What it taught me is that my memory is highly selective. I didn’t remember much about the book (having last read it in 1981) but I did remember one scene in particular! Go me! Except it turns out what I forgot can be summed up as “every important aspect of the novel.”

Driven by the memory of his father Unoka’s shameful indolence, Okonkwo has striven his whole life to live up to his personal ideal of the Ibo man: brave, hard-working, and prudent, someone who fulfills every duty his society demands of a man.

At a cost.

Okonkwo cuts himself very little slack, fearing that he is his father’s son.Thanks to years of effort on his part, he is a man of some standing in the village of Umuofia. He may reach even loftier heights before his death. This brings only a sort of grim satisfaction to Okonkwo.

If his success fails to make Okonkwo happy, it does even less for those unfortunate enough to live with him. Ever vigilant for signs of weakness, Okonkwo is even more demanding of those around him and easily provoked to violence. He conceals affection carefully; he would rather kill someone dear to him than appear weak.

But years of hard work can be undone in a single moment of bad luck…

~oOo~

Nice to know that “toxic masculinity” is present in many places,times, and cultures.

He might be a judgmental, wife-beating, murderous bully who feared looking weak more than he loved his adopted son, but I will admit I find Okonkwo’s work ethic and his determination to press forward regardless of circumstance and basic reason admirable. ‘Tis a pity that his inflexibility sabotages him. The author — and history — are not on his side.

This was, I think, the only novel by an African writer I was ever assigned in the whole of my academic career, from kindergarten to university. I suspect that this isn’t so much because books by Africans were rare, although I suppose they might have been (at least in Canada), but because I sense that this book fits a particular model of what an acceptable African novel should look like. Let me quote the NYT (from the back cover of my copy, presumably from its review of the novel back in the 1950s):

”Things Fall Apart takes its place with that small company of sensitive books that describe primitive society from the inside. In a few years, there can be no more. Then these books will become a rich storehouse for the future, full of nostalgia and (perhaps) a never-to-be-recaptured truth.”

—The New York Times

If I were to compare that paragraph with the cover of How to Suppress Women’s Writing, how many parallels could I find?

The one scene I remembered from this novel was the one in which a European explorer bicycles into a village and is promptly murdered by the fearful locals. It turns out that while that foreshadows the coming of the British (and changes that Okonkwo cannot accept), the encounter happens comparatively late in the novel. Not only that, it is one that Okonkwo hears about only second-hand. My memory played up the post-contact material and completely erased the portrait of Nigeria in the years before direct contact with Europeans. But I am certain there is absolutely no significance to which bits I remembered and which I forgot1.

I snagged this off my shelf because, as surprising as this may sound, sometimes I find myself classifying books rather too cursorily, and I wanted to remedy that. I had this mentally filed under “first contact novel.” Which I suppose it is, but that’s not all it is.

Things Fall Apart (and other Achebe works) may be purchased here.

- One of the early scenes sent me off on a research binge, looking for info about tobacco in Africa. It was only through an extreme act of will I resisted looking at the general history of New World crops in Africa.