By Women, About Women

Women of Wonder (Women of Wonder, volume 1)

By Pamela SargentEdited by Pamela Sargent

21 Feb, 2015

0 comments

Ah, the 1970s. Some later authors would have you believe that it was a vast wasteland until it was redeemed by the passage of time and the appearance of their first books. In fact, it was a vibrant period for science fiction, and one of the most significant developments was an influx of talented women into the field. As Damon Knight remarked in the early part of that decade, all the interesting new authors were women, with the exception of James Tiptree, Jr. It’s remarkable how often this sort of faux pas happened. If you were a person of the male gender commenting on SF in the 1970s, making some comment about James Tiptree, Jr. that would later appear to be hilariously misinformed would seem to have been de rigueur.

To be honest, the wave of women flooding into SF was the continuation of a phenomenon that began in the 1960s. (My perception that this is a purely Disco-Era thing is because that was when I personally began to explore SF in an ordered, methodical way.) Before the 1960s, the fraction of spec fic authors who were female was comparatively low; however, there was never a time when no women at all wrote SF — although no doubt various members of the He Man Woman Haters Club [1] would have preferred it if there had been none. Some would no doubt like if there were none now.

The 1970s was also a golden age of anthologies. Which brings us to Women of Wonder, an anthology of science fiction stories by and about women, edited by the talented Pamela Sargent. She’s been reviewed on my blog before and she will appear here again. Not just because I plan to track down and review all of the books in this anthology series, but because I think she’s that good.

This anthology of SF stories by women and about women has an introduction, but no overt manifesto. There is nothing so handy for my purposes as a mission statement or even a brief foreword along the lines of ” Screw you, Poul, women do too have a place in science fiction.” A line on the book’s back cover, a line that reads “Science Fiction and Women’s Studies,” makes me think that this book might have been aimed at an academic market. Perhaps that’s why Sargent didn’t feel that she had to justify doing a collection of SF by and about women. I can assure you that other anthologists and magazine editors presenting similar collections have felt that that they needed to explain just why they were doing this unprecedented, weird thing. Sargent trusts her readers.

One important point I should mention up front: the stories in this anthology were not commissioned for this anthology, but were collected from a variety of sources. I’ve added the year of publication for each story.

Introduction: Women in Science Fiction (Pamela Sargent):

Sargent provides a fifty-odd page history of women in SF, as authors and as characters; she assembled the book in 1974 so that is where her history leaves off. It is interesting, from this later standpoint, to note how many of the authors are familiar and how many seem to have fallen by the wayside. Despite having read this just … forty years ago [2] … I am embarrassed to admit that, not only are there authors here whom I have somehow forgotten, there are authors in this anthology whom I have been intending to track down since Bill Davis’s first term but never did.

Sargent’s introduction is of course constrained by the space available, but it is a perfectly decent pocket history of women in SF, as seen from 1974. There’s also a fascinating multipage footnote that documents a discussion between Le Guin and Lem about The Left Hand of Darkness. This discussion suggests that Lem had notions about women and gender went well beyond retrograde — in which case it is just as well that Lem didn’t include more female characters in his fiction.

The Child Dreams [1975] (Sonya Dornan):

This is a short poem in which, despite all the efforts of society to prevent this very thing, a young girl dreams dreams in which she is neither dependent on nor subservient to a man [3].

That Only a Mother [1948] (Judith Merril):

Anxiety about the effects of the background radiation, particularly on the unborn, is something that everyone has to live with in these troubled times. A young woman gives birth to a baby girl who, to her mother’s eyes, could not be more perfect.

Merril is better known as an editor than as a writer these days, but the odds are pretty good that if an anthology includes a story of hers, it will be this one. In addition to providing a nice example of post-atomic anxiety, it illustrates how social views on certain other matters have evolved. (I will discuss these matters when I get to the McCaffrey story.)

Contagion [1950] (Katherine MacLean):

Would-be interstellar colonists are taken aback when they discover that their target world has an undocumented human population already in residence. The world in question has an ecosphere for which humans are biochemically unsuited. The previous lot of colonists managed to solve that problem. Unfortunately for the latest wave of settlers, the solution will require them to make some uncomfortable accommodations.…

MacLean, who turned 90 this past January 22nd, has not been very active in recent years, but when this came out she was well known for stories like ” Pictures Don’t Lie” and had just won the Nebula for her novella “The Missing Man”. Rereading this story in the context of this collection makes me appreciate just how much mileage authors got out of body horror back in the day.

The Wind People [1958] (Marion Zimmer Bradley):

I can’t untangle MZB the person from MZB the author and nothing in this story suggests I should.

The Ship Who Sang [1961] (Anne McCaffrey):

Helva was “born a thing and as such would be condemned if she failed to pass the encephalograph test required of all babies.” Helva passes and so this story isn’t two sentences long. Conditioned to dutifully serve real people, installed as the living computer of a durable starship, Helva can expect to live for centuries. Helva may be nigh-indestructible but her living crew isn’t, an issue that is going to cause her considerable emotional pain.

This is the story that inspired me to go back and add the original publication dates. Even by the standards of the 1970s, which I can assure you were not a bright and shining time of acceptance as far as gimps and limpers go, McCaffrey’s basic assumption in the first sentence (of course any deformed child who could not serve some socially useful purpose would be humanely euthanized) raises eyebrows … now, and I suspect would have done so for a few people then.

To be honest, I know that while majority views may have changed, it would be trivially easy to find some modern who is enthusiastic about killing freaks. Cruelty and inhumanity to the weak is after all a core value for many people, not just within SFdom.

But at least Helva’s starship is shiny!

When I was Miss Dow [1966] (Sonya Dorman):

A shape-shifting alien adopts the form of a human woman for the convenience of a visiting human; she finds that being a human woman is not a lot of fun.

The Food Farm [1966] (Kit Reed):

A young woman of unfashionable plumpness is dispatched to a special school that will reshape her into a form of greater social utility to her parents. She is inspired by her schooling to apply all she has learned about diet and weight control in ways the authorities did not anticipate.

I interviewed Reed once and still feel physically ill over what a terrible job I did of it.

Of the seven stories reviewed so far, five involve reshaping women’s bodies into ones more useful, or at least more acceptable, to society. It is saddening to note that while cultural expectations regarding feminine appearance have changed (slightly) over the years, what has not changed is that women are expected to conform to a narrow (and as far as I can tell, deliberately chosen for their difficulty of attainment) range of shapes and sizes. This story could be submitted for publication today and — as long as Reed didn’t pick an editor who won’t knowingly buy from a woman — would probably be snapped up as timely.

Baby, You Were Great [1967] (Kate Wilhelm):

There are even worse things than having a body that could potentially make a woman a valuable commodity; one of them is being the only woman suitable for a whole new field of exploitation, one that subjects her to continuous, intrusive monitoring. The new field is being developed by a couple of geniuses who are, even by the standards of the mid-sixties, utterly despicable people.

I was reminded of D.G Compton’s 1973 tale of a terminally ill woman exploited by a voyeuristic society, The Continuous Katherine Mortenhoe.

This very very good story makes me regret (again) that SF lost Wilhelm to the mystery genre. Damn them and their wretchedly large audience which can provide a living wage to mystery authors. Bastards.

Sex and/or Mr. Morrison [1967] (Carol Emshwiller):

The narrator becomes obsessed with the fat man living in an apartment directly above; eventually this leads to a fairly impressive invasion of privacy and an uninvited intimacy that is not rewarded as the narrator desires.

I believe that the author intended her narrative to be touching. I just found it a depiction of an unwarranted trespass.

It’s yet another story about how we see other people’s bodies. Hmmm … I wonder what other protean stories would look like after having re-read this anthology.

Vaster Than Empires and More Slow [1971] (Ursula Le Guin):

Is this the first Le Guin I’ve reviewed here? I think it is. Set in the same Hainish universe that provided the background for so many of her stories, this one features a troubled group of explorers who set out to study worlds far beyond the old Hainish borders, worlds that offer far more alien perspectives than the HILF-occupied worlds of the old Hainish realm. They discover that sometimes the worst punishment is getting what you asked for.

My WSOD (willing suspension of disbelief) evaporates when I read SF in which humans have come to Earth from the stars. Someone like Larry Niven has the excuse that he’s just some ignorant SF writer; given SF’s proud ignorance of biology, we should just be happy he gets the numbers of limbs on humans more or less correct. Le Guin, however, comes from a family of anthropologists. She had to have known better! Whenever I read her Hainish stories, there is always a thought in the background: this could not possibly have happened. I wish I could ignore this, given that her stories are otherwise wonderful, but I cannot excise the Hainish backstory, because it is so inextricably a part of that world.

[My editor, who has two anthropology degrees, begs to differ. Oh well.]

This is considered one of the classic Le Guin stories. My take on it: as first contacts with the authentically alien go, this could have gone a lot worse for the explorers, who were a lot more out of their depth than they realized.

False Dawn [1972] (Chelsea Quinn Yarbro):

In a world that has not quite finished its descent into Hobbesian chaos, a young woman’s developing alliance with a one-armed man is threatened by a well-armed bandit, a fellow who doesn’t have much use for the one armed man and only one use for the woman.

I’m still not keen on stories whose plot consists of a community-building episode of rape and rescue.

Yet another story about form and how society reacts to non-conformity. I am starting to see a theme.

Nobody’s Home [1972] (Joanna Russ):

After what I am going to assume was a horrific period of adjustment, Earth is home to a reasonable number of wealthy, healthy, and comparatively intelligent people. Surely, the weakly post-human people of this world wouldn’t be just as spiteful and petty towards those they see as their inferiors as modern humans are, right? Right?

You can go into a Russ assuming it will all work out happily in the end but if you do that, you will end up naked in the shower, sobbing while you frantically abrade yourself with a bleach-soaked scrub brush. Best to keep a certain emotional reserve.

Of Mist, and Grass, and Sand [1973] (Vonda N. McIntyre):

This Nebula-winning story is set on the same used-up and desperately poor Earth that McIntyre featured in her 1974 debut novel, The Exile Waiting and was later incorporated into the 1978 fix-up novel Dreamsnake. A healer wanders the desolation, offering what help she can from her limited and unorthodox medical resources. Unfortunately, her advanced biotech-based medical tools take an unexpected form. Earth is a planet of small-minded hicks and she is very poorly paid for her services.

***

A recent play had the line “[…] as you will learn, people are kinda dicks.” I must say that this keeps coming to mind as I read these stories.

I usually have a pretty good memory for when I encountered books that I read as a teen. For a long time, I could tell you exactly where each book was when I first saw it. Women of Wonder is an exception. I know I owned it, I know I read it, but for the life of me I cannot remember when or how.

Alas, time and head injuries are stealing all my memories.

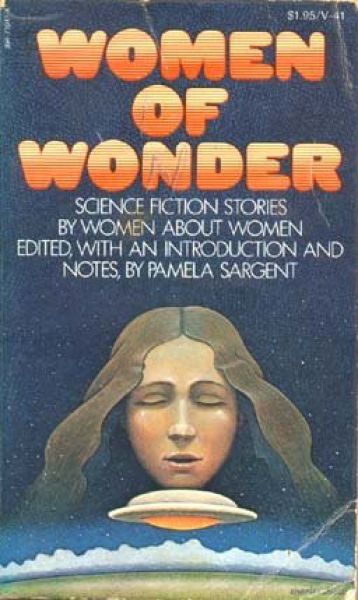

I do seem to remember the cover from the Vintage edition [4], which went for five dollars, FIVE DOLLARS! at a time when a mass-market book would run maybe a buck-fifty. Maybe I got it from the library? But I was sure I owned it.…

I have not reread this in years and while I trusted the editor as far as the prose was concerned, I was a little worried that there would be some values dissonance thanks to the age of the anthology and of the stories it contains. Having read it, I am more bothered by the fact that majority social values have not changed more than they have; in some ways we’ve moved backwards. Not every story in this collection is about people, in particular women, being constrained by the absurd and cruel expectations of society, but the ones that are could be printed today and in many cases not stand out as being from a different time.

1: I would just like to pause at this juncture to thank the creators of Little Rascals for that term, which has been quite useful to me and which I foresee continuing to use for many decades to come.

2:

3:Today seems to be my day for “this thing reminds me of that other thing.”

4: I believe the art director who oversaw the Penguin cover deserves special recognition. Here is that cover: