Christ, what an imagination I’ve got

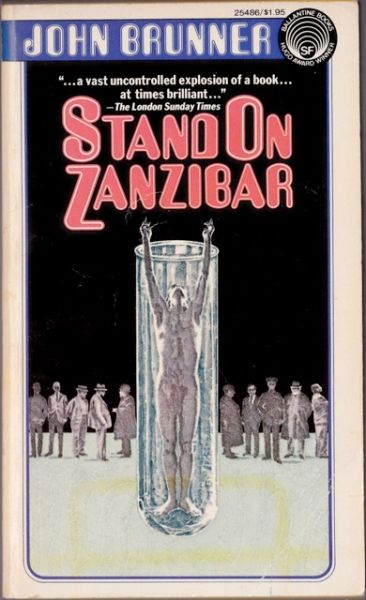

Stand on Zanzibar

By John Brunner

22 Nov, 2015

Because My Tears Are Delicious To You

0 comments

1968’s Stand on Zanzibar is the first of a thematically connected series of dystopian novels, each wrestling with a different significant issue of the day (the day being the 1960s and 1970s). It is arguably John Brunner’s finest work.

Brunner takes us to a 2010 where Earth is home to so many people — seven billion! — that if we all stood shoulder to shoulder in one location, we would cover the island of Zanzibar. There’s no sign of a Malthusian collapse on the horizon, but the unthinkable overcrowding has had consequences, ranging from draconian eugenic laws to outbreaks of violence. Conventional sexual mores have broken down and society has become saturated with frivolous, pandering, Murdochian mass media.

Two roommates, Donald Hogan and Norman House, are drawn into seemingly unrelated events on the opposite sides of the Earth.

21st Century Africa is a continent still in the throes of nation-building. The former colonies are busy accreting into larger nations, like Dahomalia and the Republican Union of Nigeria with Ghana. Tiny Beninia has no interest in being absorbed into either Dahomalia or RUNG. Independence means cutting a deal with the vastly powerful General Technics, Norman House’s employer.

Beninia is crowded and desperately poor, but for GT it offers a foothold in Africa and a place where the resources from GT’s troubled Mid Atlantic Mining Project could be put to good use. Beninia also offers an entirely different kind of resource, but it will take the entirety of the book for Norman and GT to figure out exactly how it is that the tiny nation has been able to avoid the kind of brutal violence seen in other African nations, such as South Africa.

Norman’s distant ancestors were African slaves; he feels some link to the continent. The other protagonist, Donald Hogan is pitchforked into a setting for which he feels no kinship at all: a tour as a spy in the South Asian nation of Yatakang. The US and Yatakang enjoy a relationship enriched by mutual loathing. Yatakang’s recent claims that brilliant Yatakangian scientist Sugaiguntung has cracked the problem of human genetic engineering have inflamed anxieties in an America obsessed with genetic purity. The only acceptable response to Yatakang’s claims is for America to acquire Sugaiguntung for themselves.

Or to silence Sugaiguntung forever. That would work just as well from the American standpoint. But there’s a problem. Until he was recruited as a spy, Donald Hogan was a dilettante, not a trained killer. In fact, it is not at all clear that he would even agree to kill his target. The US has an answer for that too: Education for Particular Tasks. Brainwashing. After he is EPTified, Donald Hogan Mark II will do whatever his bosses demand.

~oOo~

One of the more dystopian aspects of this book is the presence of Chad Mulligan, pundit, a tedious windbag (social commentator, I think the term is now). I could have done without him. Various SF authors have characters a lot like this annoying blowhard and none of those characters are ever bundled into a passenger rocket before being shot into the sun. This is my disappointed face.

The setting is an unusual mix of extraordinary prescience

- supercomputers the size of books,

- a peaceful end to the Soviet-American Cold War at some point in the book’s past,

- the rise of China as a global power,

- absolutely no sign of the mass famines lesser authors were writing into their overpopulation epics

with the bog-standard obsessions of the Bell Bottom Era, like eugenics. Also a bit off: the fact that the world has only a handful of supercomputers the size of books and not, say, one or two in every home. The result is a future that isn’t at all like the 2010 we actually got, but one that we can imagine having happened a few timelines over.

I was greatly disappointed by the absence of women with agency. Women in SoZ are seen primarily as mothers or as commodified sexual partners. Norman and Donald routinely borrow each other’s girlfriends for sex and neither of them seems over-concerned about what the women might think about this. The two female characters in positions of power are portrayed very negatively. This novel does not so much reject Woman’s Lib as completely fail to notice its existence.

Brunner’s treatment of his Asian and African Ruritanias is more nuanced, which is more than I expected, considering when the book was written and given SF’s dismal track record in this regard. Rather extraordinarily, Brunner was able to imagine an Africa not locked in endless wars, coups, and counter-coups. Indeed, one of Beninia’s problems is due to two neighbouring regions recapitulating the Germanies’ accretion into Germany. Similarly, Brunner’s Yatakang comes off as an odd mishmash of Indonesia and North Korea but while Yatakang’s history and culture is nothing like the actual history of the region, it does actually have a long history to which Brunner alludes; it didn’t just spring into existence when the first European explorer sailed into the region.

The book is structured somewhat ambitiously … even, dare I say it, literarily. The narrative chapters tracking the adventures of Norman and Donald are interspersed with short chapters collaged from newsflashes and bits of sub-plot that track minor characters. These chapters create a convincing background for the more traditional main plot. Brunner borrowed this technique from Dos Passos, according to the Brunner exegetes who have read Dos Passos. A select group that does not include me, but I trust them. As lesser writers have since demonstrated, it is a lot easier to bungle Dos Passos’ style than to do it well; Brunner makes it look easy.

By 1968 standards, this is a very long novel: my mid-1970s mass market paperback clocks in at 650 pages. It is an impressively quick read for such a lengthy tome. This perhaps because it was written pre-word-processor (Brunner wrote this on a Smith Corona 250 electric typewriter). It’s long because it needed to be long, not because technology made it easy to blather on without much effort. Brunner chose his words carefully.

Readers appear to have agreed with my assessment of this novel; it won a Hugo, a BSFA Award, and a Prix Apollo (as well as being nominated for a Nebula back in the days when Nebula nominations were not suspected of tracking mutual obligation in SFWA). Sadly, my memory of various Brunner essays in the 1970s suggests that Brunner was not rewarded with sales commensurate with the effort that went into creating this novel1, which ultimately led to The Great Steamboat Race debacle.

Stand on Zanzibar is available from Orb.

1: This is where I should go into a long, rambling account of other SF authors whose ambitious spec fic efforts were met with a long, loud silence from the readers. Philistines! [shaking cane]