“Cursed, cursed creator! Why did I live?”

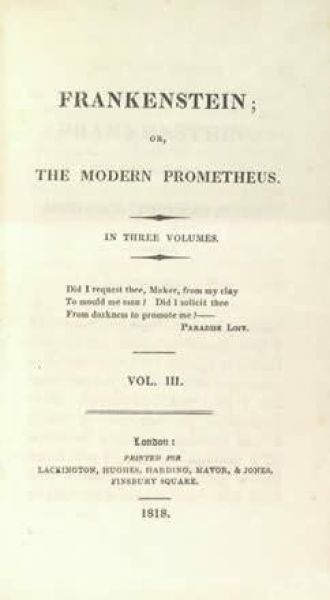

Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus

By Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley

18 Oct, 2015

Because My Tears Are Delicious To You

0 comments

The Monster from Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus is one of the great iconic figures in Western fiction; the story in which it appears is also well known. Unsurprisingly, the idea that a woman was able to create a work of great significance is confounding to certain people. Some have reacted by claiming Shelley did not write the novel, others by claiming that a story that has remained in print for two centuries is mere trash, the kind of thing a woman would write. Mountains of nonsense have been written about Frankenstein over the centuries and now it is my privilege to add a stone to those mountains.

Note: this is a review of the 1831 edition of Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus, which differs from the 1818 and 1822 editions.

Captain Walton has sailed to the high arctic, where he is sure wonders unparalleled await him. The ebullient Walton will never see the pole, but he is entirely correct about the wonders. Indeed, as he sits in his ice-locked ship, the wonders seek him out in the form of a dying traveler, whose miserable tale follows:

The elder Frankenstein’s concern for a friend fallen into poverty leads to love between Frankenstein and his friend’s lovely daughter, marriage, and children. The world will suffer for their love, because amongst their spawn is Victor Frankenstein, who will demonstrate why many RPGs distinguish between intelligence and wisdom. In a world where most people languish in terrible poverty1, Victor enjoys the love of his parents, wealth, education, even a delightful foster-sister for him to marry once they are older … which is kind of creepy2, but period appropriate and not out of character for Victor to accept as his due.

A moment of inspiration gives Victor the secret of imbuing matter with life. His techniques are not powerful enough to create a golem (clay into man), but he does manage to assemble a man from fragments of the recently dead. And what a man! His creation is a towering giant, able to survive in conditions that would kill the standard-model human, an artificial being with a mind arguably as a brilliant as Victor’s.

Sadly enough, this giant does not meet Victor’s exacting standards for other people in one important respect: he is hideous. Rather than demonstrate an iota of the affection his family lavished on him, Victor abandons his so-called Monster to survive as best it can. Which, despite the fact most of the people the Monster encounters are violently xenophobic, he does. More than that, the Monster acquires words and letters and enough of an understanding to ponder its place in the world. Having reflected, the Monster is consumed with rage at its neglectful master.

Still, there is something Victor can do for the Monster, something that only Victor can do for the Monster, something that will convince the Monster to retreat into peaceful isolation. But can Victor bring himself to make the choice that doesn’t lead to carnage and misery all round?

~oOo~

I have not read this in forty years or more. I was a bit surprised to discover that a lot of what I remembered about the story was wrong. Or perhaps I should say that my memories were based on a different version of Frankenstein, the radio play CBC aired in the 1970s. It was a pretty good adaptation, but by necessity compressed. Some incidents were made even more dramatic; Old man De Lacey comes to a tragic end in the radio version, for example.

I would review the radio play, but the version we taped off the radio wore out decades ago. CBC still had the masters the last time I asked about the play, but they could only give me a copy if I could get releases from everyone involved saying it was OK, which didn’t seem practical even in 1990.

Because I was remembering another version of what is now modern myth, there were many details of the 1831 edition that came as delightful surprise. One of them is that Shelley, like so many other authors of the time, likes digressions. We are treated to the backstories of various ancillary characters. A modern novel wouldn’t have bothered to explain how Victor’s parents met, or how the De Laceys came to live in their little hut in the forest. It’s surprising that Frankenstein didn’t end up as long as Les Miserables.

While many of the digressions seem, to the modern reader, to serve no purpose other than elaborate decoration, the De Lacey interlude is meaningful. It makes the family’s later treatment of the Monster look even worse. It lets Shelley take a few shots at the Turks and trot out some propaganda in favour of women’s rights. How considerate of the Turks to provide the English of the early 19th century with an example of a society whose treatment of women even the English could view with contempt.

I can’t say that I approved of the scheme to marry Elizabeth to Victor; arranged marriage seems to undermine the whole women’s rights angle. But it’s hard to reject everything that society tells you is OK, so I’ll cut Mary Shelley some slack. Also, the arranged marriage with Elizabeth parallels the marriage the Monster requests from his creator. All the Monster wants is what Victor was given by his parents: a suitable bride.

Shelley is also willing to toss in various implausible coincidences to keep the wheels of the plot spinning. For example, the Monster’s aimless rambling will eventually bring it back into Victor’s ambit. Victor could have ridden the morning dew to the Moon and plot necessity would still have brought the Monster to his side.

European societies of the time were ruled by monarchs and aristocrats (for the most part; France oscillated between revolutionary fervour and reaction); they were stratified and grotesquely unequal. The book reflects that reality. It’s much better to be rich than poor, better to be a peasant in Switzerland than an oppressed wretch in the Orkneys. Just as Shelley is inconsistent in her attitude towards women’s rights, she is inconsistent in her aspirations towards social justice. Justice for the oppressed but … some bloodlines really are better than others. Take the scene in which Elizabeth, Victor’s bride-to-be, is discovered living with her well-meaning but desperately poor foster parents.

One day, when my father had gone by himself to Milan, my mother, accompanied by me, visited this abode. She found a peasant and his wife, hard working, bent down by care and labour, distributing a scanty meal to five hungry babes. Among these there was one which attracted my mother far above all the rest. She appeared of a different stock. The four others were dark-eyed, hardy little vagrants; this child was thin and very fair. Her hair was the brightest living gold, and despite the poverty of her clothing, seemed to set a crown of distinction on her head. Her brow was clear and ample, her blue eyes cloudless, and her lips and the moulding of her face so expressive of sensibility and sweetness that none could behold her without looking on her as of a distinct species, a being heaven-sent, and bearing a celestial stamp in all her features.

Some people are more equal than others.

A detail whose significance I did not understand when I read this as a kid involves the title of one of the books the Monster read during his period of self-education: Sorrows of Werter, which I take to mean the work I know as The Sorrows of Young Werther. Of course the Monster adores Young Werter:

In the Sorrows of Werter, besides the interest of its simple and affecting story, so many opinions are canvassed and so many lights thrown upon what had hitherto been to me obscure subjects that I found in it a never-ending source of speculation and astonishment. The gentle and domestic manners it described, combined with lofty sentiments and feelings, which had for their object something out of self, accorded well with my experience among my protectors and with the wants which were forever alive in my own bosom. But I thought Werter himself a more divine being than I had ever beheld or imagined; his character contained no pretension, but it sank deep.

It’s not surprising the Monster would have encountered Sorrows; it may be somewhat obscure now, but it was hugely popular in its time. I understand why someone in the Monster’s situation would find Sorrows appealing. At the same time, knowing that Sorrows was one of the Monster’s strongest influences explains so much about his later indulgence in passion. How different this novel might have been had the Monster fixated upon Zeno of Citium or the Buddha!

What I took away from this late-life re-reading is that Victor is a terrible, terrible person — not because he had the hubris to create life, but because he abandoned his creation as soon as it stopped being fun. It’s not that he played at being a god and failed. It’s that he played at being a parent and failed at that. There is a monster in this book, but it’s not the being who carries that name.

Various editions of this and other Shelley works are available on Project Gutenberg, unless it turns out that the TPP has increased the lifespan of copyright to eternity.

1: The factoid I recall is the standard of living in Great Britain at this time was comparable to the standard of living in the less pleasant bits of Central Africa now.

2: Wife husbandry is ick but period. Nothing in the novel comes close to the creepiness of the Percy Shelley/Mary Godwin (later Shelley; only sixteen at the time)/Byron/Claire Clairmont (stepsister of Mary, also sixteen) unsanctified-by-marriage ménage in Geneva, in 1816, during which time Frankenstein was written. Percy had eloped with Mary, leaving behind a pregnant wife, Harriet, who later killed herself. Percy married Mary after Harriet’s death. He indulged himself in a few more illicit amours before drowning in 1822.

One of these affairs may have been with Claire, his wife’s stepsister … but this has never been proven.

Percy may not be number one on the Hikaru Genji Memorial List of Real People Who Have Preyed Upon the Young and Defenseless, but I am sure he is on the list somewhere.