Evil will come and you will welcome it

The Birthgrave (Birthgrave, volume 1)

By Tanith Lee

30 Oct, 2015

0 comments

1975’s The Birthgrave wasn’t Tanith Lee’s first novel but it seems like a good place to begin my new review series, A Year of Tanith Lee.

There were a number of reasons for this choice:

- DAW has just reissued it, so it’s easily available.

- I believe that it was this book that established Lee as an author of significance; it was a Nebula nominee,

- When I solicited suggestions for Lee books to review, this was one of the works that turned up in list after list.

The Birthgrave is of particular interest to me because hard as it may be to believe, even though I have been aware of its existence for OH GOD FORTY YEARS HOW CAN IT BE FORTY YEARS some time, I’ve never read it. There as a reason for this, a very stupid reason. More on that later.

Centuries after the fall of her great and terrible people, an amnesiac wakes deep underground. Berated for her people’s sins by a bodiless voice calling itself Karrakaz, tortured with a glimpse of her own monstrous reflection, the amnesiac is offered death — but chooses instead to flee the caverns, into a world populated by the ignorant descendants of the humans her people once enslaved.

The villagers she encounters offer her worship. She rewards them with death.

The world has fallen long and hard after the great plague that swept the amnesiac’s people from the face of the planet. The humans who inherited the world don’t remember much about those who once ruled them; what is remembered is regarded as myth, for the most part, not history. And different cultures have different interpretations of those myths.

Although the amnesiac lacks the full range of seemingly supernatural abilities that maturity would have granted, the abilities she does have (regenerative abilities that render her nigh-unkillable although not immune to pain, a face that must be hidden behind a mask lest it strike men dumb) make it clear that she is one of the vanished gods.

Her abilities make her valuable to those who can manipulate her. Her ignorance makes her vulnerable to manipulation. Not everyone worships her as a god; some see her merely as a means to power.

Over and over, she is forced to make disquieting accommodations, buying survival at a terrible cost. Over and over, she reinvents herself: as god, as warrior, as courtesan, and often, as prisoner and pawn. Over and over, those who seek to use her discover that to use the amnesiac in their plans is to embrace their doom.

For wherever the amnesiac goes, there follows Karrakaz, sowing death and terror.

~oOo~

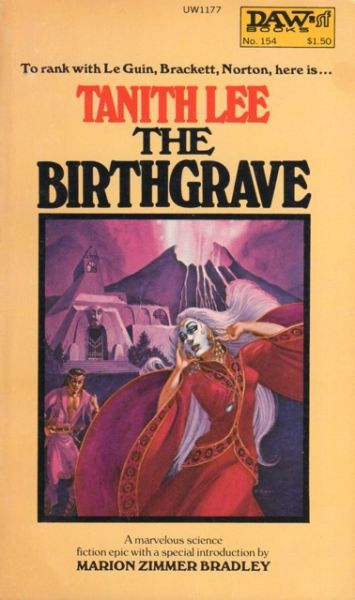

The edition I am reading is a DAW mmpb from January 1986, which means that it has a Ken W. Kelly cover

rather than the George Barr original I am using above. It also has the Marion Zimmer Bradley introduction that the first edition promised but did not deliver. MZB was very enthusiastic about The Birthgrave, as a feminist work and as an adventure novel on par with Jirel of Joiry. Given MZB’s status at the time, I can see why Donald Wollheim thought a MZB introduction would be an asset. Pity that the production error kept the two-page introduction out of the first edition.

You might wonder from my plot description how this is feminist. Well, for one thing its basic assumption is that a woman’s journey of self-discovery is as worthy of a novel as any man’s and that journey, as plagued as it may by the machinations of men, is not focused on which of them will end up possessing her. Indeed, from the very beginning, she possesses herself. For another, this is a world where all the myths someone might manipulate to gain power center on goddesses; there are no gods of note. Men wishing to exploit myth will have to bind themselves to an appropriate woman.

Lee doesn’t restrict herself to conventional Disco-era genders; the amnesiac isn’t precisely female as that term was understood in the 1970s. In modern terms, she might be intersexed; the text is open to various interpretations.

The author uses female pronouns; the book covers show her as a woman; she can carry a child to term. Yet something about her (Lee isn’t specific) marks her as intersex, neither completely male nor totally female. Because the amnesiac is dealing with barbarian cultures with rigid gender roles, she has to be conceal her [whatever it is that marks her as intersex] as carefully as she conceals her awful face. While Lee’s terminology is archaic, the text indicates no prejudice I noticed against people whose gender does not fall exactly into male or female.

While Lee may be coy about the exact details of the amnesiac’s plumbing, she revels in other gritty details. Some heroines may subsist on dew and excrete only lemon-scented rainbows (and they certainly don’t have to worry about why their period is late). The amnesiac isn’t one of those sort of characters and that was, as I recall, almost unheard of in 1970s SF.

The reason I didn’t pick this up in 1975 was because in 1975 I was very much a science fiction fan and this looked to me suspiciously like fantasy. Why, this was one of those books like the Andre Norton fantasies — books with dubious terms like “witch” or “warlock” in the titles! I was too much of a proud science and tech nerd to patronize crap like that1. Sure, I would resort to reading the odd fantasy (like The Dragon and the George) if there was absolutely no respectable SF to be found, but for the most part I avoided such nonsense.

The silver lining to my youthful arrogance is that those great works of fantasy that I did not read then I can now read for the very first time! Like saving the dessert for last …

In this case, the joke is really on me because as much as this starts off looking like a fantasy, by the end of the novel it is clear this is within the mainstream of science fiction. Mind you, it takes quite a while for the flying saucer to show up.

This is a dense novel3; there’s lots of action for people who like that sort of thing, but the text is more than mere adventure. I will say the explanation as to what is going on and what the amnesiac has to do resolve their issues is a very mid-1970s resolution to the amnesiac’s situation, but entirely consistent with what came before it. I think if I had read this novel in 1975, I would have found it heady, subversive material.

The Birthgrave is available in a shiny new edition from DAW.

1: What was my university major, you ask? Poly Sci/Econ, for which I prepared in high school by taking math class after math class, in a discipline for which I was not especially suited

2: And it’s not that I was avoiding books by women in favour of books by men. As far as I was concerned, the 1970s were a golden age of SF books by women, women like Butler, Clayton, Eisenstein, Hughes, Killough, Lynn, McIntyre, Randall, and Vinge. I just didn’t like fantasy. Give me plausible stuff like psionics, faster than light travel, and vast industrial complexes in space by the year 1999!

(Earthsea was OK because it had boats.)

3: My edition is literally dense because this is one of those production-cost-saving editions with teeny tiny print; there is more book here than mere page count would indicate.