“The shark swam out to his deepest waters and brooded in the old clean currents. He was very hungry that season”

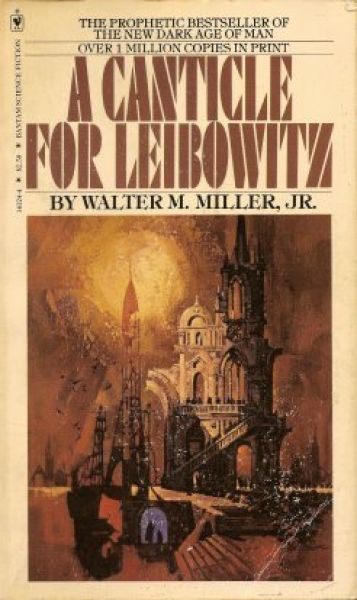

A Canticle for Leibowitz

By Walter M. Miller, Jr

20 Oct, 2014

0 comments

Walter M. Miller, Jr. was a respected and prolific author whose career as a published author was confined for the most part to the 1950s. Despite the comparative brevity for his career, he won two Hugo awards in that time, one for “The Darfsteller” and one for the only novel he ever published while alive, A Canticle For Leibowitz. If modern audiences know Miller at all, it’s usually for this novel.

Canticle is actually a fix-up of previously published novellas, “A Canticle for Leibowitz”, ““And the Light is Risen” and “The Last Canticle”, which Miller reworked, retitled and turned into the three sections of his novel, “Fiat Homo”, “Fiat Lux” and “Fiat Voluntas Tua”.

Sometime in the near future of when Miller was writing, the experiment with mutual deterrence turned into a flirtation with what Herman Kahn might have called “magnificent first strike.” While exactly what happened is obscure, whoever began the war did not manage to keep their enemies from striking back. The survivors of the exchange decided to take a pretty disappointingly negative view of the whole affair and turned on anyone involved in facilitating the war. This expanded into the Simplification; books were burned and all those deemed suspiciously literate were murdered by mobs.

As ad hoc social movements go, the Simplification seems to have been surprisingly successful (and also wide-spread – no other nation seems to be doing significantly better than the former United States of America). The efforts of the war and the loss of the educated classes cast civilization into a dark age it would be over a thousand years in escaping and it did so so thoroughly that unlike the nations that rose after the collapse of the Western Roman Empire, nobody seems to lay claim to being the legitimate successor state for the USA. In fact, the names of the nations of our time seem to be somewhat in doubt.

Fiat Homo

Six centuries after the Flame Deluge, the Order of Leibowitz, a small brotherhood of monks in an isolated abbey on what used to be Route 66, does their best to preserve the knowledge of the pre-Flame Deluge days by finding, preserving and copying documents from our time. Brother Francis is a devout if not over-bright member of the order, who thanks to a chance encounter with a wanderer leads him to discover a fallout shelter filled with relics from before the Flame Deluge. Much to Francis’s surprise, the relics seem to be directly linked to the Order’s founder, once one of the engineers responsible for the Flame Deluge. The well-meaning Francis’ discovery shapes the rest of his life, much of it in unfortunate ways, but despite frequent setbacks he never loses his religious conviction. In the end, his years of work prove invaluable, although not to him.

Fiat Lux

Six centuries after Brother Francis, civilization has recovered enough that not only can some few monks of unusual insight make use of information in the memorabilia, scholars elsewhere are independently rediscovering what was once lost. Thon Taddeo Pfardentrott is the Newton of his era and the chance to visit the abbey in person is irresistible. At the abbey he finds an astounding treasure of preserved knowledge and a kindred spirit in Brother Kornhoer.

Alas, rather like Leibowitz, Thon Taddeo buys the opportunity to be a scholar by making himself useful to the powers-that-be, in this case his ambitious cousin Hannegan, Mayor of Texarkana and would-be ruler of much of the South-West. Although Thon Taddeo’s overwhelming pride probably would have been enough to drive a wedge between him and the Brothers, Hannegan’s bold moves to unify the South-West ensure the failure of the enterprise.

Fiat Voluntas Tua

Six more centuries see the rise of nations as great and greater than any of our time. Old technologies are rediscovered and new ones, like star-flight, are developed. This time, nations have the memory of the Flame Deluge to guide them and although nuclear weapons were redeveloped and arsenals assembled, all the nations of the world agree that they can never be used again.

The problem with nuclear weapons is that to not have them is to offer one’s enemies the chance to use them without risk but to have them is to risk a general exchange. The Atlantic Confederacy and the Asian Coalition decide to settle for a long, stable cold war, relying on fear of a Second Flame Deluge to deter actual use of nuclear weapons, an idea that didn’t work the first time it was used 1800 years ago.

As it becomes clear that the Second Flame Deluge is nigh, the Order of St. Leibowitz is faced with two challenges. One is to relocate the Memorabilia off Earth, now doomed unless the current crisis can be resolved peacefully, and the other is how those who will remain on Earth will comport themselves during the slowly accelerating race to total Armageddon.

I’ve seen people refer to Miller as a one-hit wonder but that is unfair, I think. It’s not that his other work was dismissible, it’s just that enough time has gone by that most of his fiction has slipped out of the public consciousness. His novel has the advantage of being of a length easy to keep in print, while shorter work are more likely to fall permanently out of print.

I think I may be fortunate in that while Canticle is an almost ideal book from a high school lit course point of view – I know this because one of the editions I have owned was intended as a course book, including the usual joy-killing questions in the back – I encountered it on my own. In fact, I think this was the book I was reading when I meant to be studying for a grade twelve exam; I remember vowing to read just one more section before getting back to studying and then finding I had finished the novel. I was fortunate that universities in the 1980s would accept even such dullards as my marks indicated I was.

I do have to wonder if in the end the monks’ efforts are not horribly misplaced. They do manage to preserve something from the mobs but that knowledge helps make possible the Second Flame Deluge. Miller is aware of the issue:

Listen, are we helpless? Are we doomed to do it again and again and again? Have we no choice but to play the Phoenix in an unending sequence of rise and fall? Assyria, Babylon, Egypt, Greece, Carthage, Rome, the Empires of Charlemagne and the Turk: Ground to dust and plowed with salt. Spain, France, Britain, America — burned into the oblivion of the centuries. And again and again and again. Are we doomed to it, Lord, chained to the pendulum of our own mad clockwork, helpless to halt its swing?

Granted, knowledge of the first Flame Deluge meant it took nations much longer to convince themselves an atomic war would be survivable than it did the first time round and that bought enough time for the extrasolar colonies to be founded; Earth may be doomed but humanity is not. On the other hand, unless the unity in the face of hostility we are told exists on the colony worlds prevails, their founding may just mean a Third and Fourth and a Fifth Flame Deluge, on and on until humans run out of worlds to burn. Miller’s short story “The Big Hunger” may be relevant here.

In case anyone cares, I did once in a university class argue that trading three extrasolar worlds for Earth was a net win and justified redeveloping the technologies that doom Earth but I don’t think I convinced anyone.

I am just going to skip on by the Wandering Jew parts, except to say that apparently Miller wasn’t a buffet-style Catholic when he was a Catholic and that non-Catholic and especially non-Christian readers should proceed accordingly. Miller does have a certain consciousness that whatever the divine inspiration for Church Doctrine, the actual institutions are staffed by mere humans with all the usual vices and foibles.

Certain aspects of the book are apparently rooted in pre-Vatican II Catholic theology, about which I know nothing. The issue of how best to respond to painful and fatal injuries may be a case in point but in Abbot Zerchi’s defense, he actually gets to put his own arguments that God only gives people the burdens that they can handle into personal effect.

I have to say that whole section about euthanasia reads very differently in the light of the author’s suicide than it did back in the 1970s. That whole section – heck, the whole book! — may be Miller’s own “To be, or not to be?” In the end, Miller decided “Not to be.” I am quite intrigued to see which of the two alternatives modern civilization settles on.

Canticle has had something like a hundred different editions since it was first published. Here is one. Some of his short works are available via Project Gutenberg, while others are available in the collection Dark Benediction. WHA’s impressive radio adaptation of the novel may be found here.