Not a Tiptree Review

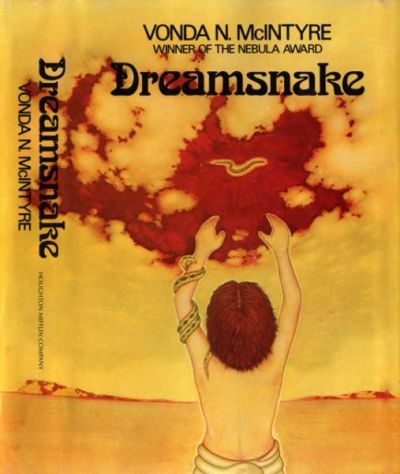

Dreamsnake

By Vonda N. McIntyre

25 Oct, 2015

Because My Tears Are Delicious To You

0 comments

Vonda N. McIntyre’s 1978 Dreamsnake is an expansion of the story begun in her 1973 novelette Of Mist and Grass and Sand. Of Mist won a Nebula and was nominated for a Hugo. Dreamsnake won both the Best Novel Hugo and the Best Novel Nebula, it placed first in the 1979 Best Novel Locus Award, was nominated for a Ditmar and was denied a stab at the Tiptree on a mere technicality (that being that the Tiptree Award was still thirteen years in the future); as it was, the novel made the Tiptree Retrospective Shortlist.

Nuclear war left much of the Earth uninhabitable, although not before the first starships left Earth and founded the Sphere. Little is left of the civilization that gave humanity the stars, and what is left is isolationist. Denied access to the knowledge and resources of the Sphere, Terrans are forced to make do with what is available on depleted, battered Earth.

Snake is a Healer, a wandering doctor who relies on bio-engineered snakes rather than conventional medicine. Earth is vast, communities isolated; cultural misunderstanding is inevitable. A momentary lapse on Snake’s part costs her her dreamsnake and quite possibly, her standing in the Healers. Dreamsnakes are valuable and nigh-irreplaceable.

Despite their name, dreamsnakes are not really snakes. They are an extraterrestrial species able to survive on Earth but biochemically very different from terrestrial lifeforms. The Healers have never been able to breed the dreamsnakes reliably; even cloning does not seem to be entirely reliable. If Center knows the secret to breeding dreamsnakes, they are not sharing it with their rustic cousins.

Or at least they have not until now. Snake encounters a badly injured woman named Jesse who, unlike her two husbands, comes from a well-born family in Center. Snake may have lost her dreamsnake but she is still a Healer. Jesse’s condition is even worse than anyone realizes, but Snake’s efforts to help her mean that Jesse’s family in Center should feel indebted to her and that debt should be enough to earn access to more dreamsnakes.

“Should” being the operative word.…

~oOo~

This is set in the same universe as The Exile Waiting and I am afraid Center isn’t any more pleasant to deal with in Dreamsnake than it was to live in in Exile.

Post-holocaust settings are to some degree protected from zeerust by their nature: nobody is going to comment on the absence of cell phones or the inexplicable presence of the Soviet Union if things have been smashed to flinders well before the story begins. The Earth is backward and poverty-stricken and even in Exile, the Sphere was mostly off-stage. The future is very unevenly distributed in this novel and most of the really shiny stuff requires a starship to access.

There is one plot element that has been somewhat undermined since the novel first came out, which is McIntyre’s fondness for what were then unconventional romantic arrangements (often but not always triads). In these modern days such arrangements are hardly worth commenting on1, save in a few sequestered backwater theocracies, but back in the Disco Era this was heady stuff.

I recall one reviewer — I am going to guess Spider Robinson because teen me always read his reviews, plus it seems like the sort of detail that would irritate him — grumbling about how the Healers knew so little about the dreamsnakes. I take his point: one would expect people to know more about a tool so important to them. But in this case, dreamsnakes are both alien and rare (you do not want to risk them in experiments) and Center is refusing to share information.

A lot of the books I review in this series have not aged gracefully. Dreamsnake is one book I think contemporary readers might enjoy almost as much as I did almost forty years ago. It is therefore with a certain amount of irritation that I note that Dreamsnake fell out of print right around the time it was getting its nod from the Tiptree Award. Happily, we live in a golden age of ebooks. Dreamsnake may have spent a good chunk of the ’90s and ’00s unavailable, but if you want to read it now, it’s a download away at Book View Cafe.

1: Oddly, McIntyre’s fictional examples of polyamorous groups rarely ran into the logistical issues that one might expect. It seems intuitively obvious that scheduling and related challenges will grow in proportion to the total number of possible interactions within the social group2. In the specific case of the people in this book that does not happen, because they are focused on Jesse’s injuries. In the general case in novels, it doesn’t happen because for some reason readers don’t want to read sixty pages about a half a dozen people trying to decide where to eat.

Some of you may be thinking “Say, I have personal experience with complex romantic situations and I feel you are grossly overstating the whole logistical complexity angle.” Well, I could trust the accumulated experience of many people or a simplistic mathematical model. Which choice do you think I will make?

2: This must be the same reason that trying to get the entire cast of a play to come to a consensus about where to grab dinner in the time available is like trying to nail Jello to a wall. Except that you can nail Jello to a wall if you freeze it, while super-cooling actors does not seem to help at all. If anything, it slows things down.