Not the secondary world fantasy you’re expecting

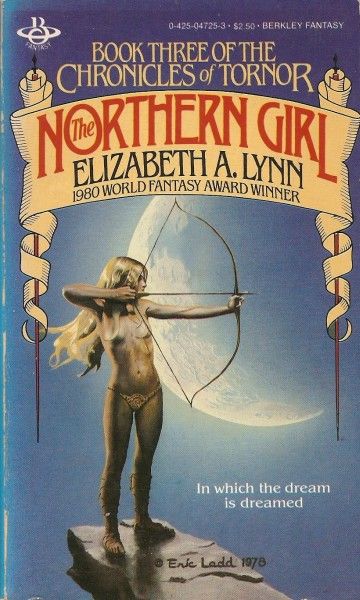

The Northern Girl (Chronicles of Tornor, volume 3)

By Elizabeth A. Lynn

23 Aug, 2015

Because My Tears Are Delicious To You

0 comments

Elizabeth A. Lynn’s 1980’s The Northern Girl, is the third book in the Chronicles of Tornor. As was the custom of those ancient days, the book works as a standalone. While reading the first two books would provide interesting context for this work, you don’t need to have read those books to understand this one. As I recall, the first two were good but this one is the longest and most ambitious of the three. It’s also not your bog-standard secondary world fantasy.

Half-a-millennium after its founding, Kendra-on-the-Delta is arguably the greatest of the cities of Arun, the land stretching from the Grey Hills to the ocean. To date, Arun has been not so much a nation or kingdom as a collection of loosely allied city-states and holdings. Now, thanks to the ambitions of a few ambitious men, all that may be about to change.

But that’s not what the book is really about.

Sorren is a seventeen-year-old bond-servant to Arre Med, one of the most powerful aristocrats of Kendra-on-the-Delta. Happily for Sorren, Arre is a good mistress and treats Sorren almost as a daughter, not as someone only slightly better than a slave [1]. Sorren is also lucky to have found love in the arms of Arre’s Yardmaster Paxe.

Sorren is an orphan who knows little of her past. Sorren’s mother spoke of it rarely; her only bequest to her daughter was a pack of Cards of Fortune. The girl knows that she descends from Northerners (as is clear from her height and colouring). She also seems to have inherited a magical talent, the gift of farseeing. This ability has been of little use to her so far: she sees only the distant past in faraway lands. Plus, the farseeing distracts her from her present duties and enjoyments.

Her mistress’s brother Isak is charming — charm is his greatest weapon — but he is also ambitious and deeply resentful. Unfair that mere birth order made his older sister Arre head of the family! Isak believes that he has found a path to power when he discovers a loophole in the law banning edged weapons from the city. If he plays his cards right, this loophole will give him unparalleled power!

It’s too bad for Isak that this isn’t a novel about how one visionary man and his allies unify all Arun, it’s a novel about Sorren. It tells us how, with the help of her mistress Arre, her lover Paxe, her mentor Marti, and the former messenger Kadra, Sorren finds her place in the world.

~oOo~

Something that would not seem remarkable in these enlightened times but which presumably got a certain amount of attention thirty-five years ago: in Arun, same-sex romantic relationships are perfectly acceptable. Presumably people in Arun gossip about who is sleeping with whom, but the fact that Paxe and Sorren are both women is an aspect of their relationship that nobody finds worthy of comment.

Gossips might find the age difference between thirty-seven-year-old Paxe and seventeen-year-old Sorren worth the odd raised eyebrow. In fact, a cynic might look at the way Paxe eventually graciously frees Sorren to seek her destiny outside the city not as bowing to the inevitability that young people will change and grow beyond their older lovers, but as a move to end the affair before it gets stale. I couldn’t help but notice that once she is on the road, Sorren herself wonders if Paxe has replaced her yet.

(This isn’t as awful as it sounds; losing Paxe frees Sorren for her next love. At least “it is desirable to stay on good terms with ex-lovers” appears to be an Arun social convention: long before Paxe & Sorren, there was Paxe & Arre…)

Lynn sets up a number of plot threads in this novel that look very familiar (and I imagine did so even way back in 1980): the scheming courtier! a political system on the brink of transformation! an orphan girl with Mysterious Powers! and maybe a Destiny! But anyone going into this book expecting a standard, by-the-numbers, secondary-world castle opera is going to be very disappointed, because that is not the story Lynn tells. Many of the reader’s expectations are subverted: Isak is more charming than cunning, and Sorren’s visions, while playing an important role in the plot, are not going to make her Witch Queen of All Arun.

Instead this book is a fairly long (by the standards of 1980s [2]) Bildungsroman, a coming of age story in which Isak’s political scheming is background, not the focus of the plot. The book begins and ends with Sorren, not with other, lesser characters.

The Northern Girl was published towards the end of Lynn’s most productive years; Lynn wrote five of her eight novels between 1978 and 1981. After 1981, Lynn’s pace slowed remarkably. There was a fourteen-year gap between 1984’s The Silver Horse and 1998’s Dragon’s Winter. It is all too easy for an author’s audience to slip away once an author’s pace slackens, but The Northern Girl has remained popular ever since first publication. There have been several reprints and editions. There’s a reason for that.

The Northern Girl, along with other works by Elizabeth A. Lynn, is available from Open Road Media.

1: I am not sure this culture has slavery as such. It definitely does not have the range of master/mistress on bondservant abuse one would expect, which in the context of The Sardonyx Net makes me go ‘hmmm.’

2: Even though the book was written in the Age of the Typewriter, it is 400+ pages. Not because Lynn didn’t know when to stop, but because the novel needed to be more than four hundred pages for the story Lynn wanted to tell.