Of historical interest only

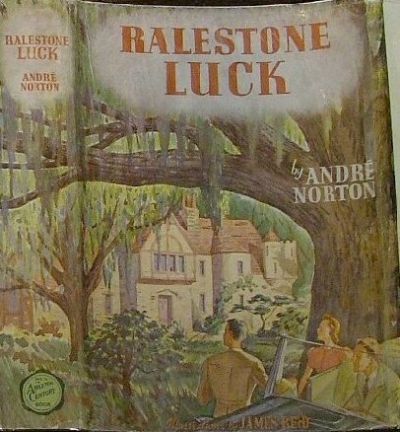

Ralestone Luck

By Andre Norton

28 Nov, 2014

0 comments

1938’s Ralestone Luck was the first novel Andre Norton wrote (although it was the second she had published) and it is one that is completely new to me. It’s actually a good thing I only just discovered this because, if this had been the first Norton novel I read, there probably would not have been a second.

Rupert, Ricky. and Val Ralestone are the last of their branch of the Ralestones, a once-great family now much reduced in circumstances thanks to poor investments made by a guardian. Once they had money to burn; now all they have is about $50 a month in investment income (something like $800 in modern terms) and a vast, crumbling estate in Louisiana that dates back to antebellum times (the bellum in this case being the American Civil War). They have even more illustrious, not to say infamous, ancestors; they descend from the Lords of Lorne, an aristocratic line whose history was sufficiently colourful that the Louisiana estate is called Pirate’s Haven.

Family legend has it that things began to go sour for the Ralestones a century earlier, when the family’s Luck, a sword “fashioned by ye devilish art of ye east,” vanished following a violent and lethal altercation between two Ralestone scions. The siblings cling to the odd belief that if only they could find the Luck, they might reverse the long, inexorable family decline.

Despite ominous foreshadowing in the form of weather, the move back south seems to have been a good idea: much of the mansion is still habitable, the descendents of the family slaves are still loyal to the Ralestones despite the freedom inflicted on them by the cruel Yankees, and over the course of the novel the siblings each discover their routes into the world of “working for a living.” Still, recovering the Luck and locating the treasure hidden somewhere on the grounds before a disloyal slave led Union troops to the plantation would be a very fine thing.

Alas, there were *two* branches of the Ralestone family and much to the siblings’ annoyed surprise, their arrival is virtually simultaneous with the appearance of a man claiming to be the legitimate heir of the other line, a claim that if correct would entitle the fellow to half the estate and half the wealth it contains. The only way to prevent this poltroon from getting his mitts on land and riches that by rights are the unearned property of the three siblings is to find evidence that his ancestor lost his rights because he was the second-born twin, evidence that demands the recovery of the Luck.

The best description I can come up for this is: imagine the Stratemeyer Syndicate commissioning a juvenile inspired by Gone With the Wind. Later Nortons focus on people down at the bottom of the heap through no fault of their own; in this apprentice novel, the three Ralestones are utterly confident that that they are natural aristocrats whose recent — recent being the last century or so — setbacks are due to misplacing a magical artifact, rather than, oh, being dependent on an outmoded and barbaric way of life.

Speaking of slavery, this isn’t quite a Lost Cause novel, but it does embrace a sunnily positive view of slavery. The one slave who had a grudge against his owners is presented as a malevolent, inexplicable figure. The rest of the African-American characters in this novel still see themselves as the natural servants of the Ralestones, monetary compensation unnecessary

“Getting acquainted with our neighbors. Ricky,” he called her attention to the smiling face just outside the door, “this is Sam. He runs the home farm for us. And his wife is a descendant of the Ralestone house folks.”

“Yassuh, dat’s right. We’s Ralestone folks, Miss ‘Chanda. Mah Lucy done sen’ me ovah to fin’ out what yo’all is a‑needin’ done ’bout de place. She was in yisteday afo’ yo’all come an’ seed to de dustin’ an’ sich — ”

“So that’s why everything was so clean! That was nice of her — ”

“Yo’all is Ralestones, Miss ‘Chanda. An’ Lucy say dat de Ralestones am a‑goin’ to fin’ dis place jest ready for dem when dey come.” He beamed upon them proudly. “Lucy, she am a‑goin’ be heah jest as soon as she gits de chillens set for de day. I’se come fust so’s Ah kin see wat Mistuh Ralestone done wan’ done wi dem rivah fiel’s — ”

Although I suppose this is of historical interest, the most positive thing I can say about this Norton is that at least it was very short so I did not have to spent too much time with the monstrously entitled trio1. I cannot really recommend that anyone read this but if you feel you must, it is available on Project Gutenberg.

1: I will give them this: they are not entirely incapable of charity, provided its object is somewhat useful to them, and once there is irrefutable proof, they do accept a newly revealed relative as a Ralestone.