One of the gentler voices of the Golden Age

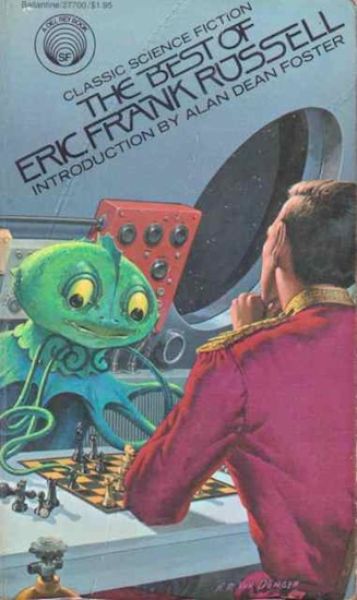

The Best of Eric Frank Russell

By Eric Frank Russell

9 Nov, 2014

Because My Tears Are Delicious To You

0 comments

This is intended, not just as a tribute to an author whose work I remember fondly, but also as a tribute to a line of single author collections that had a huge impact on me when I was a teenager. Under various series names, Ballantine’s Classic Library of Science Fiction collected the short works of various pulp-age notables, authors of whom I might otherwise have remained ignorant. I very quickly learned to snap up anything from Ballantine (and later, Del Rey) whose title was of the form “The Best of [Unfamiliar Author Name Here]”. This Eric Frank Russell collection was one of those books, and one of the better purchases I made in 1978.

Most of Russell’s stories appeared between the late 1930s and the late 1950s; only a handful of his works were published after 1959. Russell’s fiction could be weird in the Unknown manner; sometimes it was Fortean; sometimes it was superficially conventional pulp SF of the sort that was at home in Astounding and other pulp magazines. Although he was definitely aware of humanity’s darker tendencies, he himself appears to have been an essentially humane man who rejected easy, violent solutions to impediments.

“The Symbiote of Hooton,” essay by Alan Dean Foster

This is the only piece in the collection that is not by Russell. Foster is one of the legion of authors who were influenced by Russell. It happens that I encountered Russell well after Foster, with this very book but in retrospect it is clear how much Russell influenced the younger writer.

Unfortunately, not only had Russell pretty much stopped writing when Foster wrote his introduction, Russell died about half a year before the collection was published. Foster does relay Russell’s explanation for why he stopped submitting stories: Russell stopped getting new ideas and he didn’t want to recapitulate old work.

Advice to all you authors out there: saying Russell has influenced you automatically gains you some level of credit with me. The downside is that if what you ended up writing is the antithesis of Russell’s fiction, I feel bitterly disappointed and deeply betrayed.

“Mana” (1937), short story by Eric Frank Russell

The last human on Earth, a man millennia old, struggles to complete his legacy before accepting death’s embrace. What it is exactly that he is working towards is unclear but only because the author has used deliberately obfuscating language.

Humanity or at least this particular human plays the same role for those to come that the various Forerunners, Progenitors and Elder Things do for humans in pulp era SF, more humanely than is the norm.

“Jay Score” [Jay Score/Marathon 1] (1941), short story by Eric Frank Russell

Jay Score, member of a despised class, endears himself to crew mates by risking his existence to save them.

“The Minority Who Showed They Were Basically OK by Risking Their Life to Save the Narrator, Who by the Way is White and also a Guy” is an old, old story. Russell gets points for writing a story whose message is “we can get along if we try”, so yay, but then goes on to say “because each kind of person has special gifts due to the sort of person they are, which is why all Space Doctors are Negroes,” which less yay. He means well but this is basically a caste system, with jobs allocated by race.

“Homo Saps” (1941), short story by Eric Frank Russell

Who are the true masters of Earth? Not humans.

Russell would return to this theme. I wonder: if it were possible to query the entities tagged as secret masters, would they agree that their lot is a good one?

“Metamorphosite” (1946), novella by Eric Frank Russell

While on the one hand the Empire is determined to keep expanding, it is also aware the galaxy is a big place filled with scary things and they are careful to take steps to make sure each new world is safe before they try to integrate it into the empire. Not enough steps, as it turns out.

I enjoyed this story when it was called “Forgetfulness” and was written by Don A. Stuart. Don A. Stuart was a pen name for John W. Campbell, the editor who bought this and this isn’t the first time I’ve seen Campbell buy a story that is surprisingly similar to one of his own. Based on various reminiscences of Asimov’s, it would not surprise me if Campbell specifically commissioned it. It could also be that Russell was working from a check list of ideas Campbell was known to like and independently arrived at a similar solution.

The story is set hundreds of thousands of years from now but …not only does everyone talk like they just walked off the set of some Jazz-era Broadway play, it’s a plot point that some English words are still recognizable. This expression I have on my face? This is my extremely skeptical expression.

Many authors were in favour of big empires or at least saw them as less bad than the alternative. Russell fought for his own empire in WWII but he is very clear on who benefits from them.

Hobbyist (1947), novelette by Eric Frank Russell

Marooned on a distant and heretofore unknown world, a human astronaut explores his bizarre surroundings, only to discover he is neither the only intelligent being on the world, nor the most advanced.

I love the nuclear fuel in this, a spool of ten-gauge nickel-thorium wire. Russell isn’t a hard SF author by any means but this one is a bit squishier than most.

Late Night Final (1948), novelette by Eric Frank Russell

Commander Cruin of the Huldian Empire has a whole fleet of heavily armed ships filled with heavily disciplined soldiers with which to conquer backward and thinly-populated Earth. None of this is going to actually help him subdue the natives of Earth.

Russell loved stories about bureaucracies being broken by social Aikido. Poor Cruin pushes, Earth pulls, happy results all round — except for Cruin’s promotion prospects.

Dear Devil (1950), novelette by Eric Frank Russell

After decades of effort, the Martians finally reach Earth, only to find it deserted and nearly lifeless, thanks to an atomic war of prodigious proportions. One Martian, a poet, decides to remain in the ruins of Earth, where he discovers that there are pockets of fearful humans surviving here and there. Can a lone Martian get the handful of humans to look past his monstrous exterior to help him save a dying world?

Not only is the poet entirely bereft of technical skills, his tool kit is basically camping equipment. Advanced camping equipment but still…

Russell was perfectly happy to go dark if the story called for it so there was no guarantee that this wouldn’t end up being about how even the best-intentioned space monster cannot save us from ourselves. One of the poet’s solutions is intermarriage: all races should mingle into one. It turns out that he does not have to promote this idea: humans enthusiastically do this if allowed. I have two problems with this:

A: This reminds me of a James White short story where the love interest is quite correctly outraged to discover part of Earth’s plan is to blandify the galaxy altering everyone to look more or less similar 1.

B: This is in no way convincing. I’ve not noticed that people in ethnically monotone nations have any trouble finding differences to argue over.

“Fast Falls the Eventide” (1952), short story by Eric Frank Russell

Humanity is ancient and the sun is dying. Despite all of humanity’s wisdom, nobody has any idea how to rekindle a fading sun. The humans could try to take other worlds for themselves but rather than embrace war and conquest, they’ve decided to choose the way of the Veblen good.

The astronomy in this story is very early 20 th century. I wonder if this was in any way inspired by Edmond Hamilton’s Interstellar Patrol stories. The Interstellar Patrol stories often featured races pushed to desperation by entropy; confronted by civilizations on the brink of extinction, the Patrol was always happy to plant a foot on alien faces to push them over the brink. Russell goes a different direction.

“I Am Nothing” (1952), short story by Eric Frank Russell

Ambitious dictator David Korman is outraged when his son, who is supposed to be demonstrating military prowess in order to burnish dad’s glory, instead adopts an enemy war orphan and sends her home to live with his father. What Korman learns from six short sentences is that war as an abstract ideal is very different fromwar seen by one of its victims.

Remember I said Russell would go dark if the story needed it? This ends on a hopeful note but it gets there via:

I am nothing and nobody. My house went bang. My cat was stuck to a wall. I wanted to pull it off. They wouldn’t let me. They threw it away.

There’s a certain lack of enthusiasm for the results of warfare that frequently turns up in Russell’s work, almost as though he had had personal experience with those consequences or was handicapped by empathy.

“Weak Spot” (1954), short story by Eric Frank Russell

For ages, barbarians have raided the worlds of the Empire and despite the fact the Empire could crush the barbarians any time they choose to, they have not. There’s a reason for this.

“Allamagoosa” (1955), short story by Eric Frank Russell

After discovering that his military space vessel is going to be subjected to an audit, Captain McNaught and the crew of the Bustler make very sure that every item on their manifest can be accounted for. The stumbling block is the ship’s “offog”, which is not just missing but is a word nobody on the ship knows. No worries, because they have a solution for that. A solution with terrible consequences.

This won the very first Best Story Hugo. It was apparently based on an urban legend with which I am unfamiliar.

Allamagoosa is available online here. Rereading it, I am struck by how the answer as to what an “offog” is staring them in the face throughout the story.

“Into Your Tent I’ll Creep” (1957), short story by Eric Frank Russell

This time it’s the Altairians who ask “Who are the true masters of Earth?”, only to discover that is not a question you want the masters to notice you asking.

Study in Still Life (1959), novelette by Eric Frank Russell

A vast interstellar realm has facilitated the growth of a bureaucracy of Brobdingnagian scale; efforts to streamline it only made it bigger. A minor functionary on a backwater work is faced with the problem of how to obtain needed equipment without undue delays. His solution depends on a keen understanding of what makes this particular bureaucracy function.

Again, a Russell protagonist succeeds not by actively resisting but by doing exactly what the system calls for with more enthusiasm than the designers of the system ever foresaw.

There are some minor works in the Russell volume under review, but none I actively resent having reread. While the collection itself is sadly out of print and Russell himself has been dead for almost forty years, he still has enough of a fanbase that some of his works are still available. I would recommend NESFA’s Major Ingredients and Entities to your attention2.

- It’s more baffling in the White story than in Russell’s, because White was from Ireland and presumably had noticed that your Catholic Irish and Protestant Irish are visually indistinguishable.

- Note that the second book includes “Wasp,” which reads differently post‑9/11 than it did before 9/11.