One of Yesterday’s More Interesting Tomorrows

The Shockwave Rider

By John Brunner

15 Feb, 2015

Because My Tears Are Delicious To You

0 comments

John Brunner is perhaps best remembered for a quartet of novels: 1968’s Stand on Zanzibar, 1969’s The Jagged Orbit, 1972’s The Sheep Look Up, and 1975’s The Shockwave Rider. I have been known to call them the Morose Quartet. There’s an unsourced claim on Wikipedia that they are called The Club of Rome Quartet. I prefer my title.

Rather like the Pohl and Kornbluth garbageman [1] novels of the 1950s, each of Brunner’s four dystopias wrestles with a different Big Issue that society faced in the 1960s and 1970s (and arguably still faces). Stand on Zanzibar looked at a world crammed to the gunwales with Seven! Billion! People!, The Jagged Orbit looked at an America where racial hatred, paranoia, and violence provide an unparalleled opportunity for gun salesmen; The Sheep Look Up was concerned with pollution-driven ecological collapse. The final novel, the one I am going to review today, was 1975’s The Shockwave Rider, whose central concern was something pundit Alvin Toffler called Future Shock: the disorienting experience of being flooded with more information than one can possibly process.

You can sort the Quartet’s four worlds into degrees of unpleasantness. As Brunner’s early 21st centuries go, The Shockwave Rider’s is fairly shiny, far better than The Sheep Look Up and The Jagged Orbit, and in many ways on par with the nicer parts of Stand on Zanzibar. It’s true that a good chunk of California was leveled in a massive quake in 1990, but by 2010 or so [2] the effects of that catastrophe have been sorted (or so people think); those refugees who could not be absorbed into mainstream society live subsidized lives of low-tech eccentricity out west. Exploitation of space allowed an end run around resource limits, and the great anxiety of the 1950s and 1960s, civilization-ending nuclear war, was ended by universal nuclear disarmament [3]. Advanced technology offers any number of goods and services, many of which may seem commonplace now, but would have been the airy product of a science fiction author’s imagination in 1975, when this novel was published.

So, why isn’t anyone happy?

As far as the common person is concerned, they live in a networked world where their every action can be potentially scrutinized. While the government plays up the positive aspects, everyone is aware that deviation from allowable norms can get one fired or worse yet, provoke a deeper inspection from the security services. Fashion rules and everything is in flux; spouses and children to be traded for the next set as circumstances demand; nobody is ever given the chance to stand still long enough to get their bearings. People are also painfully aware that the rules are different for different people, although they don’t quite grasp the extent of it until the end of the novel. The more powerful you are, the less closely you are monitored. There is even a chosen elite above all laws.

The citizens are offered various coping mechanisms — drugs and therapies — but these are curiously ineffective, almost as though it was in someone’s interest to keep the bulk of the population confused, anxious, and disoriented.

Nick Halflinger has better reason than most to be nervous: in a world where nations are caught up in a brain race, he was one of the weapons, the product of a covert government program designed to create the geniuses of tomorrow, as the government conceived of them. After absorbing thirty million dollars worth of increasingly traumatic, dehumanizing education, Nick fled. Ever since his escape, he has drifted from identity to identity, using the very special skills he has learned in order to manipulate a nation-spanning computer network. The book does open with Nick as a naked prisoner strapped to a chair, so the alert reader may sense that at some point, Nick’s past is going to catch up with him.

Before that happens, Nick is going to have a series of learning experiences, some painful and some not. His struggle against the government has been a lone one, but there is another group out there that also stands in opposition to the status quo: Hearing Aid. This group would be natural allies for Nick if he could wrap his mind around the idea of working with others. Hearing Aid offers a curious service: they will listen to anything callers care to say, promising that only one person will listen. All they will do is listen. Hearing Aid has somehow managed to evade (or more accurately deter) the pervasive system of official monitoring.

Sadly for Hearing Aid, the people running America really do not care for people who try to buck the system. Time is running out for Hearing Aid. If info-war techniques turn out not to be sufficient to deal with the thorn in the government’s side, not all of the nukes were mothballed.…

I could say that this book is pre-Cyberpunk but if I did that I’d have to explain what cyberpunk was (a briefly fashionable sub-genre of the 1980s. which had the marrow sucked from its bones in an astonishingly short time). I don’t know if the authors in the cyberpunk movement credited Brunner as an influence (and don’t have the time right now to research it). My impression is they tended to downplay the SF of the 1970s (and to completely erase female authors) in order to make themselves look better.

I tried to reread this book on a previous occasion and failed. After this (successful) reread, I think I have figured out why I didn’t like it. This is a very, very talky book, one in which characters lecture each other at the drop of a hat. I don’t find the lectures all that engaging, so for me they are not a plus. There are also moments when one is reminded that Brunner wasn’t quite as up on his research as he tried to appear:

In China, too, the sheer pressure of population had forced an advance from ad hoc improvisation along predetermined Marxist-Maoist guidelines to a deliberate search for optimal administrative techniques employing a form of cross-impact matrix analysis for which the Chinese language was peculiarly well adapted.

This section is entered in my notes as “Carlos bait, pg 51”. I would be willing to wager that Brunner knew about as little about Chinese languages as I do — or less — but that he tossed off that bit of Orientalist nonsense because he could be assured that his readers would be even more poorly informed than he was [4].

From time to time, Brunner’s powers of extrapolation fail him: he imagines a world where computer networks span continents, where every home is wired into the net, and where a vast store of information is there for those who think to look for it — but he also imagines a world where pocket phones have to be plugged into handy phone-jacks before being used. Like pretty much everyone in the Disco Era, he buys into the ideas of people like Stine and O’Neill; his early 21st century is one in which space teems with factories [5].

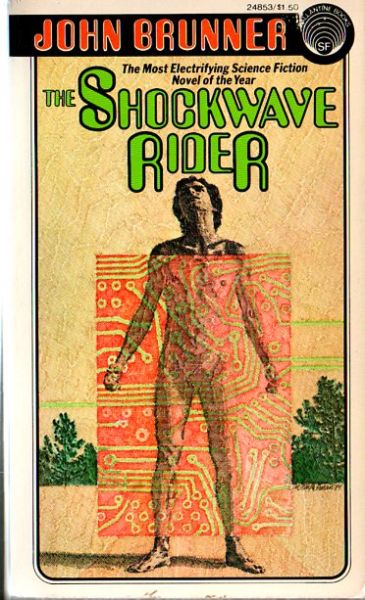

I asked my (much younger) exgf about the cover font, which, if I have not screwed up, should be visible above. She said that it’s what old people thought the present would be like back when the present was still the distant future. That’s not a bad description of the book as a whole. In Brunner’s defense, he put a lot of thought into this vision of the future and while portions of it are hilariously irrelevant to our present, other aspects are curiously on the mark. It’s not just that Brunner was among the first to use what we would now call malware as a plot point in a novel; he got a lot of other things spot on as well.

Brunner’s 21st century is one in which control of information is essential to the control of society. While certain information is actually concealed, there are a fair number of damning secrets that are protected through obscurity and distraction. It doesn’t matter, for example, if the knowledge that there is an entire class of people above the law is out there for anyone to stumble over if everyone is too busy and too confused to frame the correct questions. Considered in that light, the government tolerance for ineffective, destructive therapies and mind-dulling drugs, as well their seeming inability to ride herd on low grade social chaos, takes on a more ominous aspect. From the point of view of the people running things, keeping the general population too stressed and busy to sit back and really think about things makes them that much easier to manage.

An amusing realization that hit me near the end of the book is that The Shockwave Rider is “A Logic Named Joe” turned 180 degrees: “A Logic Named Joe” is about the need to put information inadvertently made freely available get back under the censor’s control, whereas The Shockwave Rider is about revealing sensitive information previously concealed by a tsunami of trivia and obfuscation.

Although it’s not really saying much, of the four books in the Quartet, The Shockwave Rider is the one that comes closest to a conventionally happy ending. Technically, it stops just short of a happy ending, with the people of America confronted with their masters’ dark secrets and offered a chance to change it all. They can vote on a plebiscite whose two propositions are:

1: That this is a rich planet. Therefore poverty and hunger are unworthy of it, and since we can abolish them, we must.

2: That we are a civilized species. Therefore none shall henceforth gain illicit advantage by reason of the fact we together know more than one of us can know.

Leaving aside questions of implementation, even to someone in the 1970s it should have been immediately obvious that Brunner was being hopelessly naïve. He could imagine his happy ending only if he ignored the sad fact that there are many people whose sense of well-being is inextricably tied to other people being worse off than they are. The author assumes that his readers will share his conviction that societies, even ones run by the Bad Guys, have an inherent duty to care for the poor and the hungry. This is so so 1970s. By the 1980s , such ideals were dead and mostly forgotten. While it may be comforting to blame Reagan and Thatcher, I am inclined to see them more as symptoms than prime causes. A lot of people voted for both of them.

Still, given the choice between 1) a happy, equitable [6] future without either artificial stress or artificial poverty, or 2) business as usual, with a few more kicks to the ribs, the reader of 1975 would naturally assume Americans would choose the first. The fates of various recent whistle-blowers make it painfully clear what people would actually choose is the comforting familiarity of business as usual, with a few more kicks to the ribs.

That glimpse of the future would have been as astounding to fourteen-year-old-James as the idea we wouldn’t be mining asteroids by 2015, but … here we are.

1: So-called because the basic idea is you look at some short term trend, such as the number of garbagemen employed by the city having increased 15% in the last decade, and then extrapolate that trend without worrying about limiting factors, and conclude that by the year so and so everyone would be employed as a garbageman. You can then examine all the issues that raises, such as where all the garbage needed to keep everyone busy hauling it is going to come from. It may seem like a silly technique, but you can write award-winning SF with it.

2: To be honest, that’s a guess from the protagonist’s age and the fact that 2005 is definitely in his past. 2015 would be a stretch.

3: Although it’s a plot point that there are still nukes available to be used on short notice.

4: Which may be why Brunner set his Quartet in the USA and not Britain. The advantage the US has as a setting is that it exports its cultural material at a fearful pace. Readers can easily familiarize themselves with the essentials of American society by skimming such works as The Last of the Mohicans, To Kill a Mockingbird, and Peyton Place.

5: There’s also the matter of how homosexuality is handled. In the world of this novel, it is an unfortunate but apparently common predilection, as difficult to shake as tobacco addiction. It’s a bad mark on a year-end job review, just like compulsive smoking, but not a career-killer. In the context of the 1970s, the 1980s or even the 1990s, Brunner’s world is comparatively tolerant. This is one area in which social views have evolved more and faster than Brunner foresaw.

6: To be honest, even in the 1970s I thought Brunner was playing fast and loose with his terms. For example, all jobs would be rated (and taxed) according to how they ranked on three axes, one of which is social indispensability. Well, who decides where each job ranks?