Out There in the Cold

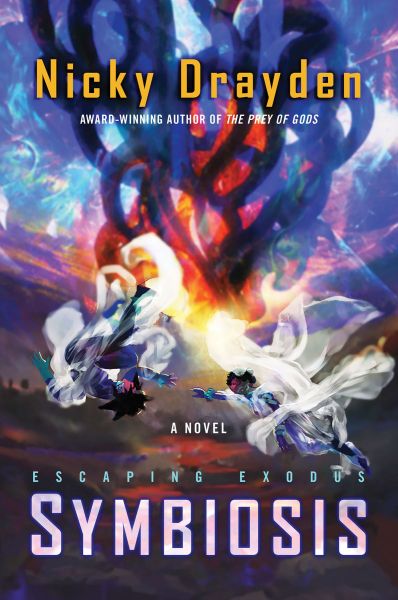

Symbiosis (Escaping Exodus, volume 2)

By Nicky Drayden

26 Feb, 2021

0 comments

2021’s Symbiosis is the second volume in Nicky Drayden’s Escaping Exodus series.

Centuries ago, survivors of wrecked Earth enslaved great space faring beasts — Zenzee — to provide new, living, habitats. Exploiting the Zenzee for human convenience rather than sustainability, humans managed to reduce the Zenzee population to a mere handful. Any evidence that Zenzee were conscious beings was ignored. Faced with the choice between business as usual and extinction OR sustainable practices and survival, the crew of the Parados embraced the unthinkable and opted for change.

Under Doka Kaleigh’s leadership, the people of Parados 1 have reformed their ways. The cost? Many personal inconveniences. Unfortunately for Doka, who has been grudgingly allowed to lead by Parados 1’s matriarchy, the other members of the Senate are unconvinced the new ways are better. They are, in fact, playing a long game.

The matriarchs believed that allowing Doka to lead would demonstrate that he, and by extension all men, were unfit to govern and that the old ways, whatever their drawbacks, are superior to the new. A crisis would arrive and Doku would fail to manage it. Doku would fall from power and the notion that men could be trusted to rule would be dismissed as a brief aberration.

Of course, when Doku is cast from power, his extended family — Seske and the others — will suffer with him. Eggs, omelet.

Parados I is dealing with more than one crisis.

There’s the matter of Parados I’s odd demographics: there are far more women than men. The folk of Parados 1 had convinced themselves that this was a side effect of living within the Zenzees, but found that other human communities in other Zenzees do not show the same pattern. On closer examination, it turns out that male fetuses are disproportionately singled out for termination by the rituals used to divide the unborn into the to-be-born and the surplus-to-needs. If this were to generally known, the matriarchy would look bad. Thus, the main witness comes down with a fatal case of being murdered. Proof certain that riling up the populace would lead to even more murder. Silence would be the best option.

There’s also the matter of the Klang, a community whose Zenzee is on the brink of death. There’s no time to save the dying Zenzee, so Parados I allows the entire Klang population to relocate to Parados I. The Klang are segregated from the native Parodosians, but there is inevitably some contact. The Klang have different ways; cultural clash is inevitable.

What the Senatorial schemers could not have foreseen is their Zenzee pod will run into a new, far more numerous, cloud of Zenzee. This is a godsend for the traditionalists. Why sacrifice for sustainability when there are so many new Zenzee to exploit? This is the perfect pretext for an attempt to oust Doka.

It is at this fraught moment that Doka and Seske add fuel to the fire by violating Parados I’s rigid marriage laws.

~oOo~

Oh, look: an SF novel in which politics beyond simplified feudalism and brute force play a role. Not that there isn’t a rigidly stratified society and the occasional stomping boot, but a lot of the book is about trying to change people’s minds about what’s in their best interests. Reform turns out to be very hard, because, to quote Upton Sinclair, “it is difficult to get a man to understand something, when his salary depends on his not understanding it.”

The novel raises the question of whether, having committed some great crime, it is possible to make amends. To be fair, that does not really get answered because contrition on the part of the powers that be is at best lip service, to be discarded as soon as practical1.

Parados I has marvellously convoluted marriage customs, which as the novel demonstrates in some detail, has equally convoluted failure modes. Come for the backstabbing politics, stay around for the romantic trainwreck.

Some readers may find the idea of senators acting in blatant bad faith purely to prop up a manifestly unjust social hierarchy difficult to accept. Presumably, even if they are drawn from a small pool, senators must be subject to some sort of selection process; people who are incapable of focusing on the big picture because they are too focused on maintaining their traditional privileges would never make it as far as the senate. That’s just simple logic! But this is science fiction so we have to accept the outlandish notion that somehow the system has failed and few bad eggs have made it through. [Editor’s note: I see what you’re doing there, James.]

Symbiosis offers an unexpectedly Poul Andersonish take on biological technology. Forced to shape the Zenzee to suit their needs (and later preferences), ruling castes have also embraced the habit of treating lower status humans as resources, to be created and discarded according to personal convenience. It does not appear to have occurred to any of the conservative rulers that turnabout is fair play.

Escaping Exodushad a cast of sympathetic people who did terrible things, convinced that these were the least bad choices available. Symbiosis puts that same cast up against people who do terrible things because they are certain privilege is their birthright. Perhaps not the most optimistic book I could have read of late, but it was certainly intriguing.

Symbiosis is available here (Amazon US), here (Amazon Canada), here (Amazon UK),here (Barnes & Noble), here (Book Depository) and here (Chapters-Indigo).

1: The humans are essentially emerald ash borerswith a talent for self-justification.