Panicky teenyboppers stampeded in tight circles, shrieking, “Dig it! Dig it! Dig it!” and knocking unwary tourists off their feet.

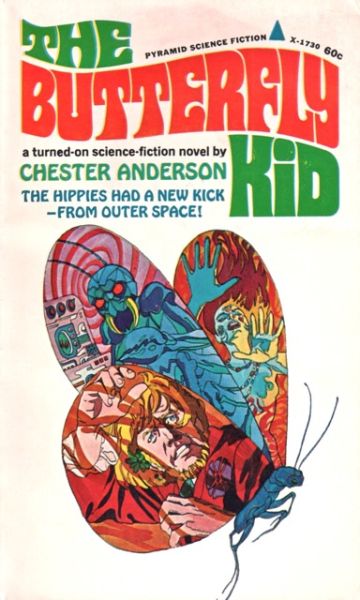

The Butterfly Kid (Greenwich Village Trilogy, volume 1)

By Chester Anderson

18 Jan, 2015

Because My Tears Are Delicious To You

0 comments

1967’s The Butterfly Kid, first volume in the Greenwich Village Trilogy, is perhaps the finest science fiction thriller in which a ragtag group of hippies and hipsters (based on real people) save the world from blue meanies. While that’s not a huge field, it’s one with surprising stiff competition.

As Chester Anderson explains in his foreword:

I always feel vaguely cheated by first-person novels wherein the name of the narrator is not the name of the author. This is irrational, but there it is. I never claimed to be particularly rational.

Therefore, I made myself a character in this book, using my own real name (with, of course, my permission). Having gone thus far, I modeled the character of my friend, roommate and manager on my real-life friend, roommate, and (quondam) manager Michael Kurland (with whom I collaborated on Ten Years to Doomsday—advt.), using, with his permission, his real name.

Both of these characters, however, are purely fictitious. They are only based on us; they are not in reality us.

Lights up on a futuristic Greenwich Village! Internal evidence points to a date no earlier than 1976, but, unlike our rather disappointing 1976, this is a 1976 where the US hasn’t descended into the corrupt, narcissistic excesses of the Me Generation. In this world, innocent hippies still roam the land and by the land I mean New York and by innocent I mean not counting Laszlo Scott.

It begins innocently enough, with a naïve out-of-towner named Sean conjuring butterflies out of nothing, something Chester assumes is a particularly cunning prestidigitation act. Chester is wrong and Sean really is creating butterflies out of nothingness. That’s pretty weird but this is the Village and nobody would have thought too much of it all if it had stopped with the butterflies1.

But it doesn’t.

It takes a while for the penny to drop but eventually Chester and his ex-spy pal Michael realize that someone is distributing a brand new drug — Reality Pills— around the Village, a drug that turns fantasy into reality. Normally neither Chester nor Michael would have an issue with a new drug, but the guy sharing the Reality Pills is none other than the notorious Laszlo Scott. It is guaranteed that if dickhead Laszlo is involved, whatever is happening has to be bad.

Or as an unlucky Chester Anderson discovers, worse than he could have imagined. Aliens have their blue, lobstery eyes fixed on Earth and the only thing between Earth and total conquest is “sixteen standard Greenwich Village heads and hipsters of various kinds.” Two of them are missing, so actually that’s only fourteen … oh, and one of them is Little Micky, who doesn’t count.

As it turns out, military prowess isn’t the primary skill needed to oppose the aliens. If the crisis involves reality-warping drugs, you could do a lot worse than to grab a bunch of kids from the Village.

This is a period piece now, but of course when it was written in 1967, Anderson was merely partaking of the zeitgeist of the time. Contrary to what some reviews claim, this is not set in 1967; however, the Summer of Love doesn’t seem to have ended in this world, Details like the ubiquitous flame-guns carried by the National Guard soldiers hint that this isn’t a utopia, but people still manage to have a lot of fun. At some point, hovercraft — remember hovercraft? They were the airships of the 1960s — became road legal and it was just as bad an idea as that sounds. Free Love seems to have lingered on and not the unsavoury version favoured by certain writers (in which women are fungible conveniences), but one in which the women make their choices from a vast selection of nerve candy.

I came at this book from the wrong angle in all kinds of ways. First, I read Kurland’s sequel, The Unicorn Girl, before I ever saw the 1980 reprint of The Butterfly Kid2. In fact, I’d given up on ever seeing the Anderson book3.

Another mistake I made was to have contact with actual hippies. When I was ten, my father took his sabbatical in Brazil and he rented our farm out to a group of UW students who came highly recommended. Or rather, the responsible one, an amiable long-hair we called Jesus for his hairstyle and pleasant demeanor, came highly recommended. There were just a couple of hitches. The first is that nobody mentioned the commune4 the kids planned to set up on the farm, although really, it was the 1970s and what the hell were we expecting? And the second is that poor Jesus wasn’t up to the stress of being the one responsible person. With him out of the picture, the other kids were free to do stuff like use a chainsaw indoors, run our van to Toronto and back with no oil, sink our canoe in Columbia Lake, and break my bed, presumably by jumping up and down on it as hippies do, apparently.

What I’m saying is, I really shouldn’t have liked this book and yet I do; it’s one of the good-natured books I reread whenever I have overdosed on grimdark fantasy or badly thought-out dystopias. I think a big part of its attraction is that Anderson—an interesting figure in his own right—has pretty clear notions about his fellow hippies and hipsters, people whom he clearly likes or at least finds endlessly amusing. However, he does so without blinding himself to their (or his own) little quirks. His fondness for his friends comes across in the text.

You may not have been aware that you want to read a book in which a ragtag team of potheads, poets, and rock-musicians5 save the world from alien blue lobsters and also Laszlo, but you probably do. Unfortunately, this is long out of print and it’s one of the books where the ebook revolution has not produced a reprint. At least I have my copy.

- This seems like a good point to admit that until this reread I completely missed the part where Sean’s butterflies smothered a vagrant. In his defense, it was accidental and also Americans don’t value human life as you or I do.

Usually I use the cover art from the edition I am reading but I think this is a case where the original suits the text a lot better than the slick 1980s cover.

Usually I use the cover art from the edition I am reading but I think this is a case where the original suits the text a lot better than the slick 1980s cover.- I did find a copy of the third book as well. Go me!

- It’s not due to encroaching senility that I occasionally think about how the commune could have been set up so that it didn’t implode, right?

- Also noted

pornographeradult erotic film director and film producerAndrew Blake, who ends up with an unwonted halo at one point.