Poindexters, Pointy-haired bosses, Villainous Third Worlders, and Dastardly Feminists.

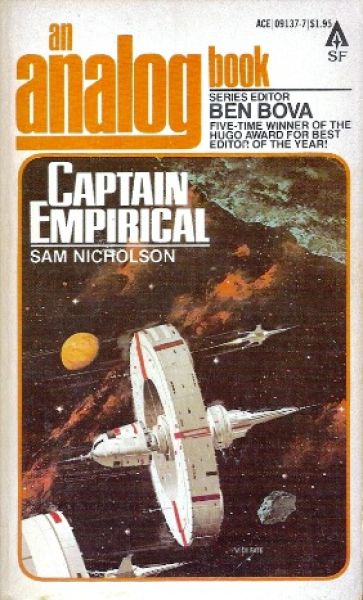

Captain Empirical (An Analog Book, volume 2)

By Sam Nicholson

14 Dec, 2014

Because My Tears Are Delicious To You

0 comments

According to ISFDB, Sam Nicholson was a pen name for Shirley Nikolaisen, about whom information is pretty scarce (Googling her name led me back to one of my own comments, which was not very helpful).What I can safely assert is that of the twenty Nicholson short works, twelve appeared in 1977, 1978, and 19791. Also, while her debut was in Jim Baen’s Galaxy, most of her short work appeared in an Analog then under the editorship of Ben Bova (ten stories) and Bova’s successor, Stanley Schmidt (seven stories).

Today’s book under review, 1979’s Captain Empirical, is a result of the Bova connection. It was published in Ace’s An Analog Book series2, edited by Ben Bova.

Either Nicholson held views that appealed to Bova and his successor, or she adopted those views in her stories out of a keen appreciation of what Bova (and later his replacement) would buy. Bova was a lot friendlier to female writers than his predecessor had been; over the course of his tenure the frequency of women in the table of contents went from 6% to 18%3. It probably didn’t hurt Nicholson that her Captain Schuster stories steadfastly took the side of the embattled white senior employee, who is menaced on all sides by Poindexters, pointy-haired bosses, villainous Third Worlders, and dastardly feminists.

Although ISFDB will tell you this is one of Nicholson’s two novels (the other one of which, The Light-Bearer, is somewhere deep in my to-be-reread pile), this is misleading. This book is a fix-up, the kind where the result is not a proper (if episodic) novel, but rather a very thinly disguised collection of short pieces.

In this book, we meet the irritable Captain Schuster. He abandons his beloved sailing ships for spacecraft, after which he and his crew discover that the asteroid belt can be just as dangerous as any place in the South Seas. While the reader knows that the Captain will always emerge victorious, his co-workers don’t know that. For reasons that vary from person to person, Schuster’s co-workers independently decide to snoop through Schuster’s private files. Each file is, of course, a story.

“The Fourth-Stage Polygraph” (1977), short story

While hunting for a miscreant, Schuster falls victim to a Procrustean device that shapes its subjects to the needs of their job. That would be bad enough by itself, but in this case it is the needs of their job as understood by the passengers of the ship Schuster is commanding. It turns out there is a significant gap between what Schuster needs to be doing and what the unfortunates sailing with him think they need.

This is only the first of the really disturbing transmogrifiers that Schuster encounters, threats that I had not heretofore realized were such a major danger to shipping. Schuster catches a case of low-grade telepathy as an aftereffect of the device, but happily that seems to wear off pretty quickly.

“Get the Lead Out” (1976), short story

Schuster gets seconded to work on the world’s only atomic-powered yacht, which positions him to deal with a pair of rascally Third Worlders who plan to steal the ship’s fissionables.

You might think this would lead to the moral that atomic power doesn’t mix well with civilian shipping, being subject as it is to piracy and the like. However, despite his brush with nuclear terrorism, Schuster thinks atomic power is woefully underutilized in the civilian realm. He blames this on bad design and is thoughtful enough to suggest that the Poindexters replace all that heavy lead with superconducting magnets. Someone does explain that magnets won’t intercept stuff like gamma rays, but Schuster is of the opinion that maybe the scientists just are not trying hard enough.

“A Rat of Any Psize” (1977), short story

A psionic rat trap turns out to work on two-legged vermin as well, transforming its victims into a species more suitable to their low moral status. Conveniently, there’s a local market for rats, whether natural-born or victims of a baleful polymorph. Unfortunately for the rats, it is the market for fertilizer.

I did consider keeping a running count of the people in whose deaths Schuster plays a role, but realized as soon as I got to this story that it would be hard to come up with a number. I can say that it would not be a small number and that Schuster is perfectly OK with the humongous death toll.

The Copra Population (1979), novelette

Schuster gets caught between Captains Karos and Eggerton. Karos is desperate to keep the cargo on his stricken ship from being transferred off the ship, because that would prove that Karos was playing crooked games with his cargo manifests. Eggerton is desperate to keep the cargo on the stricken ship from being transferred onto Eggerton’s vessel; said cargo is rat- and insect-infested and Eggerton has a pathological fear of vermin. Alas for Karos and Eggerton, Schuster is there to make sure the cargo does get shifted. Schuster always wins in the end.

Warning: this features the tragic death of a cockroach who loved too well but not wisely. Schuster feels sadder about the poor roach than he does any of the humans who die in his vicinity.

Actions Speak Louder (1978), novelette

Schuster begins his transition from sea captain to space captain when he is seconded to the Company’s ambitious space exploitation program. Although he is but a hairy-eared old salt, he takes it upon himself to completely redesign the program, entirely successfully of course. His reward for that is to participate in the first serious mishap on the surface of the Moon.

Schuster’s gripe, or one of his gripes, about the original plan to exploit space resources with a free-orbiting station called the Wheel is that he feels such things are not expandable. A Moon colony, however, can be expanded piece-meal. While I take his point about the volume of a habitat, down on Earth you can do a lot with the interior of a building while leaving the outside the same. What I am working my way around to is I’d love to see How Space Stations Learn as the basis of a story.

“Griggs and the Einstein Fallacy” (1977), short story

Back at sea, Schuster tries to dispell a ship’s curse. His solution relies on technobabble and some serious woo. Along the way Schuster foils the IRA — remember when fictional terrorists were generally Irish or at least Red Fraction? — while providing vital moral support to a man whose doleful marriage to a harridan has left the poor fellow terminally depressed.

Schuster casually kills a helpless IRA member in this story, apparently as a lead-in to a brief tirade about relativism and relativity. It happens that the person listening to this tape is the company lawyer, who is taken aback by the cheerful way Schuster admits (on tape!) to murder.

“Now You See Her” (1977), short story

Schuster foils a needlessly convoluted insurance scheme.

The bad guys are using a genuinely innovative hologram projector. I am reminded of an old Mark Shaw Manhunter issue, wherein Shaw openly mocks a supervillain who uses his transmutation device to rob banks. The crook then bets on the Cubs. Shaw points out there are dozens of legal ways to make money from the ability to temporarily transmute things.

More Deadly Than the Male? (1978), novella

In which Schuster wrestles with a foe more terrible than pirates, terrorists, or accountants: Woman’s Lib! The Company can hire either Ellerdown, a plucky, hard-working girl with a solid work record, or Copps, a make-up-wearing slutty college girl, a Straw Feminist who compensates for her lack of real world experience with an enthusiasm for lawsuits.

As an added bonus, Schuster explains why girl employees are inherently riskier than men and why it is they have to be paid less.

When I read this a decade ago, I concluded that:

I seem to remember that Nicholson’s [Shirley Nikolaisen in real life] second novel wasn’t this dire but going on Captain Emperical, I’d guess the career killer was the relative dullness of her stories. Sexism with just the right amount of sneering at Third-Worlders would have gone over well in Bova’s Analog, given enough gadget content to keep the readers content. The fact that these stories could have been written by a computer with a few programed guidelines wasn’t as annoying when each story was encountered by itself but rereading the whole set of them together was dreadful, a complete waste of hours of my life. These are the perfect examples of the [Platonic] Ideal of the Bad Analog Story with the stock villains, the stock heros and stock plots which can make an Analog issue an exercise in exquisite tedium.

I think I was being just a little harsh there. Also I somehow forgot to mock the truly ghastly technobabble and the captain’s casual attitude towards murder (both of which traits are true to the traditions of Astounding/Analog). This collection isn’t good, but it is instructive in that it illustrates all the flaws I would expect from Analog stories of this era.

That quote also demonstrates that that I missed something way back then, something I only noticed on the current re-read. In the intervening decade, I listened to hundreds of episodes of Escape. While Nicholson is framing her stories so she can pitch them to Analog and its ilk, she’s drawing pretty heavily on the shipping adventure tales of yore, Any one of her stories set in the South Seas or East Asian waters could easily have been featured by old-time radio shows like Escape, Adventures of the Sea Hound, or Terry and the Pirates.

-

Because I demanded it! The number of short works per year:

That productivity curve is not an uncommon pattern in authors. Neither is the preference for specific venues (or perhaps particular editors). I do wonder what happened to her.Year # Editor 1975 1 Baen 1976 1 Bova 1977 4 Bova x 4 1978 3 Bova x 3 1979 5 Bova x 2, Schmidt x 3 1980 2 Bova x 1, Schmidt x 1 1981 0 1982 2 Schmidt x 2 1983 0 1984 0 1985 1 Schmidt x 1 -

This series ran from January 1979 to February 1980 and comprises:

- Analog Yearbook by Ben Bova

- Capitol: The Worthing Chronicle by Orson Scott Card

- Captain Empirical by Sam Nicholson

- Projections by Stephen Robinett

- The Best of Astounding by Tony Lewis

- Maxwell’s Demons by Ben Bova

- A War of Shadows by Jack L. Chalker

- The Best of Analog by Ben Bova

- Hot Sleep by Orson Scott Card

- The End of Summer: Science Fiction of the Fifties, edited by Barry N. Malzberg and Bill Pronzini

- Class Six Climb by William E. Cochrane

I think I still own all but the Cochrane.

-

Schmidt tossed that little innovation over the side almost immediately; women authored a mere 9% of the fiction that appeared in Analog in his first year as editor. This was typical for his run as editor (so far as I can tell). Which I guess makes Nicholson one of the lucky few women to be kept on. I wonder if Schmidt knew that Nicholson was a woman.