Sea Story

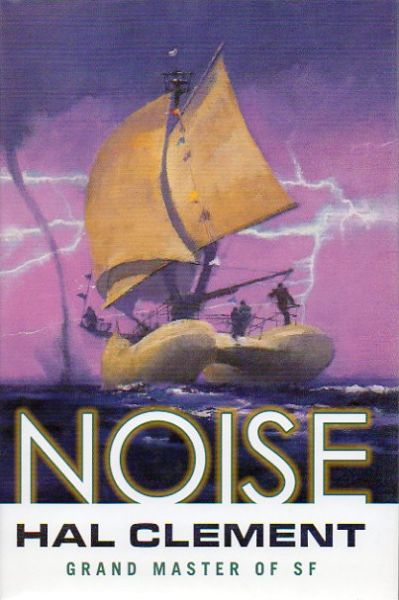

Noise

By Hal Clement

8 May, 2015

0 comments

Hal Clement’s career spanned seven decades but he was never a particularly prolific novelist [1]. Although he published five novels in the 1950s, after that he never put out more than one or two a decade [2]. Despite this comparatively small output, he was still considered a significant enough figure that he was named the 17th SFWA Grandmaster in 1999. His 1954 Mission of Gravity is considered a hard SF classic; his 1949 Needle may well have been the first science fiction mystery novel of note.

2003’s Noise is noteworthy for an unhappy reason: it was Hal Clement’s final novel, published only about a month before he died.

~oOo~

Centuries after the water world Kainui was settled by a diverse assortment of Polynesians, Terran linguist Mike Hoani arrives to study the languages that have evolved on that distant world. What he finds is a world unlike any other.

The planets Kainui and Kaihapa orbit each other, like the earth and the moon; the double planets in turn orbit a pair of close-orbiting red dwarf stars. Both Kainui (the settled planet) and its near-twin Kaihapa (as yet unsettled) have far more water than Earth; their oceans are 2700 kilometers deep! There is no solid land. The acidic oceans have never given rise to native life and the atmosphere is composed of gases of entirely abiotic origin. The dense, largely opaque atmosphere limits visibility to short distances, and the abundant thunderstorms jam most radio frequencies. The world ocean is roiled by shock waves propagating upwards from the solid surface of the planet, 2700 kilometers below the surface of the sea. The planet’s core is still molten and highly tectonically active. Kainui is a deafening, blinding world, one that poses extreme challenges to the people who call it home [3].

The people of Kainui are neither especially welcoming nor especially unfriendly to off-worlders; for the most part, they do not care about events off-world. Of all the floating cities on the ocean surface, only one has any interest at all in off-world trade. Despite this insularity, Mike doesn’t have much trouble finding a job (which is less than a matter of necessity than a way to immerse himself in the world and its languages). He joins the crew of the Malolo: Wanaka, her husband Keokolo, and young ‘Ao. The ship crisscrosses Kainui’s vast ocean, harvesting pseudolife for useful materials.

There is no native life on Kainui. The empty ecological niche is filled by pseudolife, a biotech-developed replicator. Its many forms sift the oceans for useful elements. Pseudolife is a well-understood technology by this point, one with capabilities as yet unused. It could be used to reshape the planet to a more human-friendly state — but it is not. The Kainuians resist the temptation to terraform. For reasons rooted in their history, they fear unregulated growth more than they resent the inconveniences of living on Kainui.

As Mike discovers, the fact that long range communication is effectively impossible means that while his companions are expert sailors, their world still holds many surprises for them, surprises that could make them rich or leave them prisoners of an ambitious city-state.

~oOo~

I wish I had not used Clement’s “the universe is antagonist enough” for the title of a review of a James White collection; that title would be very apt for this review. While there are human antagonists in this story (rumours of pirates, mysterious and possibly malevolent strangers), this final novel is really about the exploration of an alien world. Other authors would have gone for Edward Teach IN SPACE! Clement prefers to thoughtfully explore the implications of physical conditions quite unlike those on Earth.

Readers familiar with Clement’s fiction will spot familiar themes. Clement had strong, present-day environmental concerns: profligate human use of non-renewable resources, unrestricted population growth. The people of Kainui have learned from Earth’s mistakes; although they lack a world government, the general (but not universal) consensus is for carefully regulated, moderate use of the world around them.

Readers familiar with Clement will recognize pseudolife as his own personal take on what would later come to be called nanotech. It may or may not have been inspired by Feynman’s earlier “There’s Lots of Room at the Bottom” it certainly predated both the coining of the term nanotech and Drexler’s book Engines of Creation. Unlike Drexler’s rather ludicrous take on nanotech (it’s dry and mechanical), Clement’s version uses plausible chemistry inspired by biology. It’s a powerful, flexible tool, but it suffers from many of the drawbacks of the biology it mirrors, including being vulnerable to mutation and natural selection; it may start off designed but it won’t stay that way. Clement used pseudolife in his 1980s book The Nitrogen Fix (where a strain of it converted most of Earth’s atmosphere to various oxides of nitrogen, which turned out to be undesirable) and in 1966’s “The Mechanic.” The appearance of pseudolife in a Clement book does not seem to be any indication that the book belongs to the same continuity as other such books; rather, it’s simply a theme of which Clement was fond.

There’s also Clement’s odd obsession with gold, which I completely overlooked until Carlos Yu pointed it out. It’s not your common goldbug monomania; it’s something a bit harder to explain. Clement seems fascinated with the physical properties of gold and, in novels like The Nitrogen Fix and Half Life, the possible unintended consequences of the human habit of concentrating the stuff. In this book, there’s a confusing subplot about a species of pseudolife that was designed to concentrate gold for use as ballast. This subplot does not seem to actually go anywhere. It’s just something Clement seems compelled to include, much as I sometimes include entirely gratuitous references to Tommy Douglas.

This book is a fair example of Clement’s work. The prose is functional. The characters are types rather than individuals. Clement didn’t really do non-analytical, wooly-minded characters, so everyone in this book is sensible, observant, and rational. The plot consists of characters encountering various unfamiliar phenomena and working out their significance. It’s essentially a series of science mysteries.

There isn’t really all that much hard SF out there, by my standards. A lot of books labeled hard SF turn out to be farragoes of nonsense when examined closely. I suspect that in some cases they are so labeled, not because of their content, but because the author has friends like Niven and his pals. Clement sometimes got the details wrong [4], but this wasn’t for lack of honest effort on his part. People looking for a solid example of hard SF might consider this novel.

As far as I can tell, Noise didn’t make much of a noise when it was released. I never got a copy for review and it seems to have had a fairly limited number of printings over the years. It is still available as an ebook, which can be purchased here. If you want a hard copy, I am afraid it’s Abe Books, Bookfinder, used bookstores (although I have never, ever seen a copy of this in a used bookstore), or the library for you.

1: In large part because SF writers of his era focused on short fiction. The mass market paperback market didn’t really bloom until Clement was twenty years into his career as a writer.

2: Number of novels per decade (by date of first serialization):

1940s: 1

1950s: 5

1960s: 2

1970s: 3

1980s: 2

1990s: 2

2000s: 1

3: On the plus side, nobody is going to want to take it from them.

4: In order to expeditiously get Mike to the world he wants to explore, Clement postulates fast, cheap FTL travel. Exploring handwavium didn’t interest Clement, so all we learn about the FTL is that it is apparently inexpensive and pretty speedy.