Thank Greece’s Alexis Tsipras for this

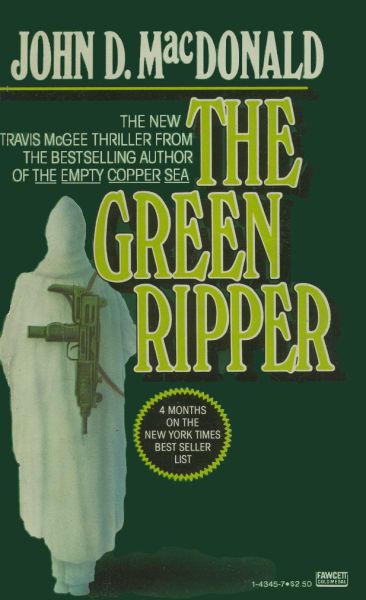

The Green Ripper (Travis McGee, volume 18)

By John D. MacDonald

12 Jul, 2015

Because My Tears Are Delicious To You

0 comments

John D. MacDonald’s 1979 novel The Green Ripper will always be a special book to me. In some respects, this book has not aged well and my review is going to face that fact head on. But it is the very first Travis McGee novel that I ever read and that counts for something.

(I know where I bought this but for the life of me I cannot recall why I bought it; I didn’t get into mysteries in a big way until a few years after 1980. My suspicion is that the decision to pick up this novel was one part eye-catching green cover and one part laudatory references to MacDonald by reviewers like Spider Robinson.)

McGee is an aging adventurer, a man with a bewildering list of odd skills picked up from friends, acquaintances, and lovers (so many lovers) over the course of a long, colourful career as a problem-solver and salvage expert.

At the beginning of The Green Ripper, McGee’s career as a two-fisted man of action seems fated to come to a well-earned end. In the course of the seventeenth book in the series, The Empty Copper Sea, McGee encountered something he hadn’t thought possible: a lover (Gretel Howard) with whom he could imagine spending the rest of his life.

McGee isn’t going to spend the rest of his life with Gretel. Gretel is, however, going to spend the remainder of her life with him.

Soon after relating an odd encounter she had at the Fort Lauderdale fat farm where she works, an enterprise that is part of a larger conglomerate, Gretel falls deathly ill. Despite the best efforts of her baffled doctors, her condition only worsens. Eventually, after enduring excruciating pain, Gretel dies.

This might seem to be the normal sort of mishap that could strike down any woman who happened to be dating the lead in an ongoing series where part of the shtick was the lead’s rotating roster of girlfriends and lovers. Except … Gretel’s boss has also just died in a sudden seemingly innocent accident. A visit from two men in suits claiming to be from an unfamiliar alphabet soup agency asking about Gretel’s final days is suspicious in itself, but what solidifies McGee’s conviction that Gretel was murdered is the revelation that the two agents and their agency are entirely fictitious. Someone killed Gretel to keep her from revealing whatever she saw that day at work. Only McGee’s reluctance to share what she told him has saved McGee from joining Gretel and her boss in sudden, convenient death.

Actual federal agents put in an appearance long enough to hand McGee information that is simultaneously revelatory and useless: Gretel was poisoned in a manner peculiar to Soviet and Warsaw Pact assassins. But the mysterious man she saw at the fat farm was someone she knew as Brother Titus, a devotee of the cultish Church of the Apocrypha. What possible connection could there be between the Soviets and an obscure community of religious nuts?

The one solid lead McGee has is the location of the cult farm where Gretel first saw Brother Titus all those years ago. After making arrangements that make it painfully clear McGee doesn’t expect to survive this vengeful expedition, he heads west to California, posing as Tom McGraw, a beat-up, no account fisherman looking for his (entirely fictional) daughter Katherine, last seen as a member of the Church of the Apocrypha.

Of course, the supposed Tom McGraw doesn’t find Katherine; she is as fictional as Tom. What McGee does find on the supposed religious commune is a training camp for idealists — sorry, a training camp for terrorists who are only one small part of a vast plan to bring modern America to its knees. A group with a use for a man like Tom McGraw, an easily led man with useful skills, but also an expendable nobody no one will miss.

A man whose true nature and purpose the group has completely failed to grasp.

~oOo~

Poor Gretel! How was she to know that McGee’s penis has powers like the protagonist of the TV series Pushing Daisies: one touch heals, the second touch kills? It’s never a good idea to be a woman who appears in two McGee novels. It’s really a bad idea to be a woman whose survival would likely mean the end of the series [1].

I was a bit hesitant to revisit this because I was pretty sure McGee’s views on women wouldn’t have aged particularly well. Well, it could have been a lot worse. It’s true that McGee evaluates women pretty much in terms of the rollicking sex he may or may not want to have with them, but at least it’s his intention to leave them as satisfied as he is. He might be a bit old-fashioned in his views, but at least he isn’t inconsiderate.

(The death-dealing powers of the Penis of Doom aren’t due to McGee, who is a gentleman; the culprit is MacDonald, who wants to keep a highly successful ongoing series unsullied by too much deviation from its basic setup.)

Since it was my first Travis McGee novel [2], I couldn’t know when I picked up The Green Ripper that this is an unusually dark McGee story, arguably the most despairing and nihilistic of the twenty-one McGee novels. MacDonald makes the tone clear right off the bat on pages 12 – 14 of the mass market paperback. Here’s a despairing conversation between McGee and his best friend, economist Meyer:

“How did the conference go?” I asked.

He shook a weary head. “These are bad days for an economist, my friend. We have gone past the frontiers of theory. There is nothing left but one ugly fact.”

“Which is?”

“There is a debt of perhaps two trillion dollars out there, owed by governments to governments, by governments to banks, and there is not one chance in hell it can ever be paid back. There is not enough productive capacity in the world, plus enough raw material, to provide maintenance of plant plus enough overage to keep up with the mounting interest.”

“What happens? It gets written off?“

He looked at me with a pitying expression. “All the major world currencies will collapse. Trade will cease. Without trade, without the mechanical-scientific apparatus running, the planet won’t support its four billion people, or even half of that. Agribusiness feeds the world. Hydrocarbon utilization heats and house and clothes the people. There will be fear, hate, anger, death. The new barbarism. There will be plague and poison. And then the new Dark Ages.

“How much time have we got?”

“If nobody pushes the wrong button or puts a bomb under the wrong castle, I would give us five more years at worst, or twelve at most.”

That sets the tone for the whole book: not only is Gretel murdered, but it turns out the murder was entirely unnecessary from the point of view of the organization that had her killed. In fact it was worse than unnecessary, because it was the attempt at a cover-up that set McGee on the path that led him to the farm in California.

In addition to being unusually bleak, this is also an unusually violent installment in the McGee series. There’s generally a death or two in each book; sometimes the deaths are due to McGee (usually acting in self-defense, of course). In this book, McGee has what he calls a John Wayne day, where he bludgeons and shoots and explodes his way through a small community of would-be terrorists. In a lot of books, the long violent sequence that comes towards the end of the book would be cathartic. That is not the case here. Because McGee spends time in the training camp, he gets to know his enemies as people who in other lives could have been friends. The result: a McGee who is not jubilant at having massacred enemies, but sickened at the violence.

The vast shadowy plot to Bring America to Its Knees could have been spun as a Red Plot (and the funding does seem to be coming from Our Pals in the Kremlin). However, the book (or at least Meyer) rejects the comfortable explanation of that this was all part of a skirmish in the Cold War. Meyer presents a much darker explanation:

“Remember when I talked about the new barbarism last December? About the toad-lizard thing with the rotten breath, squatting in its cave? You met it, Travis. You felt the lizard’s breath. It is man’s primal urge to decimate himself down to numbers which can exist on this wornout [sic] planet. It is man’s self-hatred. The god of the lemmings, and of the poisonous creatures that can die of their own poison.”

Some of you may be saying at this point “Meyer, seek help.” I am afraid it gets worse for Meyer before it gets better. As I recall, McGee is luckier; The Green Ripper’s grim tone does not foreshadow the direction the rest of the series took and he will recover from the disturbing events in this novel.

The Green Ripper and other Travis McGee novels are available from Random Penguins.

1: Of course, a few years later, in 1985’s The Lonely Silver Rain, MacDonald introduced a supporting character who would have transformed McGee’s life — had future novels in the series appeared. Unfortunately, McDonald died in 1986, leaving The Lonely Silver Rain as the final installment.

2: I became very familiar with McGee thanks to the coincidence of two events: 1) I took a job as a security guard that involved a lot of night shifts alone in empty factories, and 2) KW Book Exchange bought an estate’s worth of books, a load that included a case of John D. MacDonald books. I happened into the store as they were unloading the books. One of the owners offered to let me buy a whole case of books for almost nothing if I did it immediately, saving them from the necessity of unpacking and sorting the books. The box turned out to contain all of the McGee books plus some other MacDonald books. But that didn’t happen until some three years after I bought The Green Ripper.