The Lord of Darkness is a jerk

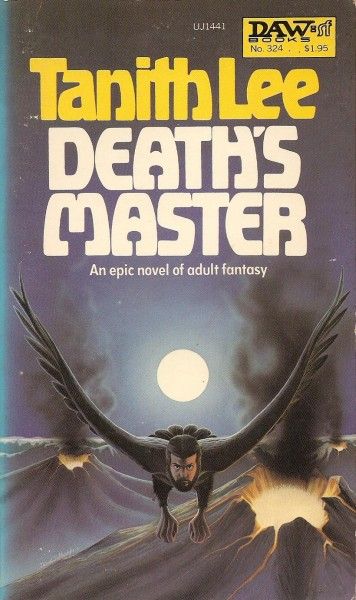

Death’s Master (Tales of the Flat Earth, volume 2)

By Tanith Lee

11 Dec, 2015

0 comments

1979’s Death’s Master returns to Tanith Lee’s Flat Earth setting. It is an unfriendly place for Simmu and Zhirem; in any world but the Flat Earth, their mutual attraction might not have been doomed. Unfortunately, the Flat Earth is not a great place for lovers, particularly for those who, like Simmu and Zhirem, are pawns in a languid game played by rival demons: Uhlume, Lord of Death and Azhrarn, Lord of Darkness.

The story begins a generation before Simmu and Zhirem are born.

After she is cursed by a dying wizard, Queen Narasen of Merh is forced (much against her same-sex inclinations) to have sex with man after man in the vain hope of breaking the curse. If Narasen manages to conceive a child, she will free herself, and her kingdom. Eventually she realizes that no living man can give her the child her land needs. She makes a deal with Uhlume, Lord of Death. The result is the gender-fluid, curse-breaking Simmu.

There is no happy ending to this deal. Narasen is assassinated and her wraith is forced into the service of the Lord of Death, thanks to the terms of the deal. She had hoped to have many more years to raise her child and protect her kingdom. The assassin is too squeamish to kill baby Simmu as well. Simmu is taken by demons, who keep it as a pet before tiring of it and dumping it in a temple.

Our other doomed protagonist, Zhirem, also loses his mother. She loved her son so much that she exposed him to the fires of the underworld, hoping to render him invulnerable. She pays a terrible price for her scheme, but she does succeed (to a great extent). Nothing in the physical world can harm Zhirem.

Zhirem and Simmu meet in the temple where both are being educated. They are both (in their individual ways) very different from the boys around them; mutual attraction is perhaps inevitable. The relationship ends badly; judgmental Zhirem blames Simmu for corrupting him, while Simmu abandons Zhirem for Azhrarn, the Lord of Darkness. The lovers have become mortal enemies.

Azhrarn hears of a closely guarded fountain of youth and sends Simmu to investigate. Simmu infiltrates the walled garden in which the well is located, finds an ally in the disgruntled blessed virgin Kassefeh, seduces all of the other virgins in the garden, and makes off with the secret of immortality. What neither Azhrarn nor Simmu expect is that this gives Zhirem, by now a powerful magician, the opening to finally take his long-delayed revenge.

~oOo~

Given all the sex (of many and various sorts) in which our characters indulge, one would expect that they would be having a lot more fun than seems to be the case. It’s true that anything demon-touched seems to end badly, but a large part of the problem seems to be Zhirem, who is a needlessly vindictive, judgmental prick.

I would like to see how Heather Rose Jones or Web of Queer would analyze this book’s treatment of sexual orientation and gender identity. It seems to little old cis-het me that in some ways this novel has not aged well. Narasen isn’t explicitly criticized for her attraction to women, but she does end up cheated and dead, which is all too much like the TV Trope Bury Your Gays. Then there’s the wizard who curses Narasen, a wizard who has been warped by abusive, predatory gay sex. That’s par for the course for this setting. Most sex here seems to be exploitative.

It’s also a world where it is stupidly easy it is to curse people1 and where all forms of immortality come with serious drawbacks. No free lunch here, nosirree.

I am inclined to blame the general fuckupedness of the setting on the fact that while the demons take an active interest in the world, the gods do not, being stuck up jerks. At least the Lord of Death isn’t actively malicious, however protective of his perogatives he is.

It’s probably too late for me to start keeping a running count of dead or missing mothers in Tanith Lee fantasies. If I had such a list, I would have to add Narasen (poisoned by a jealous witch, dies soon after her baby is born) and Zhirem’s mother (exiled to the desert, where she becomes a tree). Another character, Kassefeh, is abandoned by no less than three parents: two fathers (for this is a magical world where biological parentage can be complicated) and a mother.

Unlike Night’s Master, this second volume in Tales of the Flat Earth is one long story. However, this story is nothing like a linear narrative. Lee fills almost 350 pages of tiny print with digressions and convolutions on her way to the novel’s eventual conclusion. There is apparently no urgency to reach that conclusion.

(It’s not all tears and recriminations: some of the characters do have fates with which they are not entirely unhappy.)

I am unaware of any recent edition of Death’s Master, which makes me sad. Given how huge print runs were in the Disco Era, you should not have any trouble tracking down a used copy of this novel of decadent hubris.

1: Curses, even death curses, should come with a Do You Really Want to Curse this Person/Kingdom? [yes] [no] step.