What have they done to the rain?

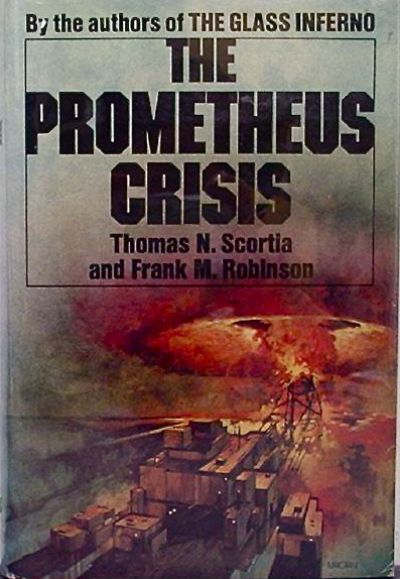

The Prometheus Crisis

By Thomas N. Scortia & Frank M. Robinson

23 Oct, 2016

Because My Tears Are Delicious To You

0 comments

ChemistThomas N. Scortia (1926 – 1986) published science fiction from the 1950s to his death from leukemia; he was nominated for the Nebula in1966. His frequent writing partner, Frank M. Robinson (1926 – 2014), was active in SF from the 1950s to his death. His awards andnominations range from the Hugo to the BFA, from the Lambda to theLocus. Robinson was also a well known activist.

Together the pair were masters of the disaster thriller. Their 1975 standalone The Prometheus Crisis is a fine example of their work in this genre.

America’s energy needs grow day by day. Oil is a staggering twenty dollars a barrel 1.The only reasonable alternative is nuclear power. Luckily, the same Americanknow-how that gave the world the Ford Pinto, the Mark 14 torpedo, and the New London school closure is at the nuclear industry’s disposal.

Attwelve thousand megawatts, the Cardenas Bay Nuclear Facility — the Prometheus Project — is the largest nuclear reactor complex on the planet. That is, it will be once the facility is up and running. The facility has been plagued with a multitude of seemingly manageable technical problems, which the higher-ups feel are mere bagatelles.General Manager Parks feels they are serious enough that it would be wise to defer bringing the facility online. But, but … the President has already announced a speech celebrating the upcoming inauguration of Prometheus and the dawn of energy independence.

Outnumbered, Parks cannot win this argument. All he can do is hope that all the flaws he sees will be of little consequence. After all, every single flaw in the equipment at Cardenas Bay, every shoddy practice adopted at Prometheus, was pioneered in other nuclear reactors. They never led to a large-scale nuclear disaster before. Why would they now?

Months later, the congressional subcommittee investigating the horrific Cardenas Bay Incident would dearly like to know the answer to that question. Or rather, they demand an answer that won’t threaten America’s entrenched interests, an answer that will allow the US to sidestep a humanitarian disaster of biblical proportions and continue with business as normal. In other words, they want a scapegoat.

And who better than that one lone dissenter?

~oOo~

Readers(and viewers, for those who just saw the films) had specific expectations where books like The Prometheus Crisis were concerned. The casts should be large, the interpersonal issues fraught. There should be many gripping subplots (so many that in writing this review, I had to skip the red herring about the terrorist working in the facility). No matter what the characters doto stop the looming crisis, they would be sabotaged by circumstance and hubris. The government would not help … or would make things worse 2.Once the plot segues from ominous foreboding to active disaster, the cast would dwindle at alarming speed, which just goes to show how high the stakes were. That’s one reason the casts needed to be large in the first place. Bad luck to be in that cast. Worse luck if you are the romantic hypotenuse.

As the covers of the book remind the reader no less than five times, Scortia and Robinson wrote The Glass Inferno ‚one of the books that became Irwin Allen’s The Towering Inferno. Scortia and Robinson, both veteran science fiction authors, were quite familiar with the conventions of the form because they helped create them 3.

The publisher and the authors are pretty upfront about the inevitability of disaster. Not only does the cover art look like the art feature above or in the case of the mass market paperback, like this

and not only does the book reveal early on that something happened at Cardenas Bay that justified congressional hearings, but the authors dedicated the book thusly:

For Bob Heinlein, who thirty-five years ago said: “Blowups Happen.”

and prefaced the book with this excerpt from Stephen Vincent Benét’s Nightmare,With Angels:

(…) another angel approached me.

This one was quietly but appropriately dressed in cellophane, synthetic rubber and stainless steel,

But his mask was the blind mask of Arcs, snouted for gas-masks.

He was neither soldier, sailor, farmer, dictator nor munitions-manufacturer.

Nor did he have much conversation, except to say,

“You will not be saved by General Motors or the pre-fabricated house.

You will not be saved by dialectic materialism or the Lambeth Conference.

You will not be saved by Vitamin D or the expanding universe.

In fact, you will not be saved.”

Those are not harbingers of a happy ending.

The authors deliver on their promise: by the end of the book, a combination of poor design, political pressure, unfortunate decisions, and simple bad luck leaves the facility a bubbling hole in the ground. The West Coast will be living with (or dying by) the results for centuries to come. Few of the cast survive to the end …and it’s not at all clear what their remaining life expectancy might be. To ensure this, the authors over-egg their pudding 4:almost everything that could go wrong does, including the decision to use Cardenas Bay to process a prodigious quantity of nuclear waste. This is not just Chernobyl (still a decade in the future) dialed up to eleven, it is Chernobyl combined with Kyshtym. Combined with the wrath of an angry, angry god. Worse, the wrath of two science fiction authors who likely had an eye on a possible movie deal 5.

Obviously, US reactor design and procedures have been sufficient thus far to spare North America a Windscale, Chernobyl, or Fukushima. Americans might have been terrified by Three Mile Island, but everything terrifies Americans, from clowns to Kinder Eggs. There were no known fatalities from TMI. I won’t say American light-water reactors will never find a path to supplying surrounding regions with electricity too cheap to meter, but thus far they have not. Regardless, disaster is what the authors are selling and disaster is what the readers get.

Much to my surprise, I discovered on rereading this book that, while thes pecific disaster is one the US has never experienced, the managerial process that leads to it is not just plausible, it is all too familiar. It even has a name: normalization of deviance. Perhaps the most famous example is the Challenger disaster (although similar factors were at play with Columbia as well). There are a lot of parallels between the lead-up to the disaster in this book and the Challenger disaster, including pressure from the Oval Office to hit an arbitrary deadline created by the President’s desire to make a speech.

The Prometheus Crisis is so completely out of print that your best bet is probably not Amazon, but your preferred purveyor of used books.

1: Bear in mind that when the book was published, twenty bucks would buy you ten mass market paperback novels.

2: Once the plant starts burning its way to China, the military does try to help. Some of them are hampered by the fact that the means by which they are monitoring the situation is top secret and they cannot share what they know without risking exposure of the secret. Elected and civilian agencies are slow to act, when they do finally act. The nadir of governmental incompetence and delusion might be the moment when an elected official chides one of the handful of survivors for focusing on the disaster and not the lavish tax advantages the plant offered the community prior to the mishap. I do wonder at the verisimilitude of this little faux pas; surely it is as unthinkableas some politician blocking first-responder aid packages for mere political points .

3: Speaking of conventions, I would like to think that the scene in which an unfortunate teenage girl is slut-shamed (because she was outside naked when she was exposed to fallout) is sadly dated. But I am probably kidding myself.

4: People interested in the same sort of process discussed in last week’s review will find the afterword interesting. Nuclear power fans may find it annoying, since Robinson and Scortia were predisposed by their background in science fiction to see new technologies in terms of how they could go wrong.

5: Not that such deals always worked out well for the two authors. On one occasion, they were very surprised to discover that a property of theirs had been adapted to television, given that they had never sold those rights, only rights for a theatrical release never made. As I recall, the people responsible for the television version concluded from the fact television rights were not mentioned in the film rights that the authors did not want money for the TV rights. Sadly, I cannot just now put my hands on Robinson’s essays wherein he discussed the frank exchange of views that followed this revelation.