What these people need is Kwisatz Haderach!

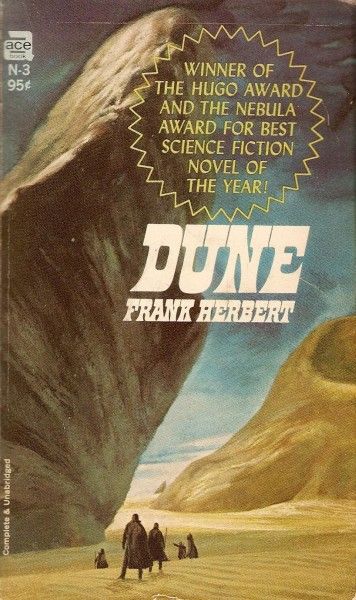

Dune (Dune, volume 1)

By Frank Herbert

15 May, 2016

Because My Tears Are Delicious To You

0 comments

Frank Herbert’s 1965 fix-up novel Dune is the first novel in his ongoing (and thanks to necrolaboration, undead) Dune series. While the original novel may be overshadowed by the feculent dribblings of Brian Herbert and pen-for-hire Kevin J. Anderson, in its day Dune was pretty highly regarded. Awards include

| Place | Year and Award | Category |

|---|---|---|

Not bad. So how does it stand up more than a half century later?

The planet Arrakis! Also known as Dune! Sole source of Spice, the mysterious substance that grants longer life and enhances awareness, even allowing a lucky few to see into the future itself! Life extension alone would make it valuable, but its role as psychic steroids makes it a necessity for interstellar trade. Without spice, ships would be lost to unforeseeable dangers in the interstellar deeps.

Whoever controls Arrakis control the Spice. Whoever controls Spice controls trade. Whoever controls trade controls the Empire itself.

That’s the theory, anyway. As the Atreides family is about to find out, theory and practice often differ.

Worried by Duke Leto Atreides’ growing popularity, Emperor Shaddam IV grants House Atreides control of the planet Arrakis. It is, of course, a trap. Any hint of falling productivity would give the Emperor reason to humble Leto. Unfamiliar with the ways of Arrakis, it would be easy for Leto to mismanage Spice production.

If the enmity of the emperor were not bad enough, Leto’s super-villainous rival, the boy-hungry Baron Harkonnen, has prepared a surprise for the Duke and his family. A deadly surprise! Full of stabbing and poison! And also killing and plots! And people explaining to each other how very cunning they are.

No plan survives an encounter with the enemy. In this case, both the emperor and the baron have made a terrible mistake. Sending Leto to Dune has sealed the Duke’s doom. Sending Leto’s son Paul to Dune, on the other hand, has doomed the emperor, the baron, and a host of innocent bystanders.

There are a number of fatal flaws in the emperor and the baron’s plan. One is that the Atreides are far better at forging bonds with Arrakis’ fierce warrior people, the Fremen, than any previous overlord of Dune has ever bothered to be. Jessica, Paul’s mother, also knows how to manipulate Fremen religion and custom. This means that when Paul and his mother flee the Harkonnen attack, they find refuge.

Worse, for centuries the manipulative Bene Gesserit have been breeding humans with an eye to creating the fabled Kwisatz Haderach, a man with the psychic gifts previously the monopoly of Bene Gesserit Reverend Mothers. Jessica’s decision to give Leto a son confounded the Bene Gesserit plan to end the Harkonnen/Atreides feud by marrying a son of Harkonnen to a daughter of Atreides. By sabotaging the peace plan, Jessica inadvertently guaranteed the success of the eugenics program. That success is a generation early and has put Jessica and her gifted child beyond the control of the scheming hags.

And by forcing the Atreides to migrate to Dune, their enemies ensured Paul would be exposed to the one substance that could trigger his buried gifts.…

~oOo~

For some reason, my high school didn’t have Dune itself, only Dune Messiah. It wasn’t until 1980 that I came across a copy of the original book. My reading of which was interrupted when some jerk stole my copy while I was shopping for textbooks. Not that I keep grudges but … I hope that guy was bitten by a goat. Or perhaps a white shark. I am not demanding.

Modern SF readers may be astounded to learn that the original stories, Dune World and Prophet of Dune, were published in John W. Campbell’s Analog. In later years, environmentalist stories, doubtless written by disgusting dirty hippies, would not be welcome in the hallowed pages of Analog. But in earlier times, authors ranging from James H. Schmitz to H. Beam Piper felt free to explore ecological themes without any fear of being taken for degenerate weed-smoking treehuggers.

As was typical for its time, Dune is entirely free of unseemly modern concepts like democracy and Women’s Lib. Herbert deploys a scheming, bloodthirsty, but plot-friendly feudalism and a robust gender essentialism. Powerful women, like the Bene Gesserit, start their careers as something between a courtesan and a dutifully-married aristocrat and end them as cruel, manipulative hags. Anyone uncomfortable with 1960s-era social changes would have found little to offend in this book.

Rereading put more focus on what now appear to be some hilariously silly worldbuilding and plotting in this book. Frex, Arrakis is plagued by whale sized sandworms plowing through though the sands. Just where do they get the energy to support their size and activity? Nothing growing on the sands. Are they photosynthetic?

The convoluted schemes that drive the plot do not seem all that cunning; they look like the sort of thing that Baldrick would consider a cunning plan. Perhaps this is the reason that the characters spend so much time exulting in their cunning. Otherwise, readers might realize that they were reading a story set in the Dunning-Kruger Galaxy.

(I particularly admire the brilliant Harkonnen scheme to subvert one of Leto’s close assistants, who has been mind-conditioned to make betrayal impossible. The Harkonnens threaten the man’s wife. Apparently nobody ever thought of that in previous centuries, during which the conditioning was held to be completely reliable.)

The appeal to Analog readers is easy to understand, but how did this become a general best seller? I think there are several factors, many of which come down to some exceptional (fortuitous) timing on Herbert’s part.

Herbert was not the only person who became intrigued by ecology in the 1960s, but he was one of the first to write an award winning SF novel playing with those themes. It is easy to stand out if there is not much competition.

I think Dune’s length also worked in its favour. This was a time when magazine SF was being pushed aside by mass market paperbacks. There would have been lots of competition for shelf space. The fact that Dune is something of a tome, three times as long as the standard for SF novels at the time, would have made it stand out. As the sales of Lord of the Rings shows, people were quite happy to read long books, as long as they were interesting and as much as I poke fun at Dune, I have to say it is not boring.

Dune also owes a lot to the hoary trope of the Mighty Whitey, the outsider who swiftly masters native arts to a degree that actual natives can never attain. Dune borrows heavily from the Middle East for a lot of its imagery. It just so happens that a couple of years before Dune saw print, there was a fairly popular movie about a Mighty Whitey who wanders the desert in search of adventure, an accomplished honky whose schemes topple an empire. Even a half century later, you may have heard of it.

Dune isn’t Lawrence of Arabia IN SPAAACE but it was as close anyone got in the mid-1960s.

This may be marketed as ecological SF but it’s really a fable about super-powers in a distant retro-future, with a moral about how you should be very, very careful what you wish for. While rereading this, I was reminded of the works of A. E. Van Vogt, who also loved grand spectacle powered by pure nonsense. Herbert is far more portentous than Van Vogt, but I suspect that anyone who likes Herbert would like Van Vogt. Hmm … perhaps I should review The Voyage of the Space Beagle.

I think Dune is an ambitious mess. It is, however, still popular enough to justify the publication of a seemingly endless stream of wretched sequels, each more dreadful than the last. If you’re curious about the original that Brian Herbert and Kevin J. Anderson have failed so abysmally to emulate, Dune is available here and here.