Yet more SF about women, by women

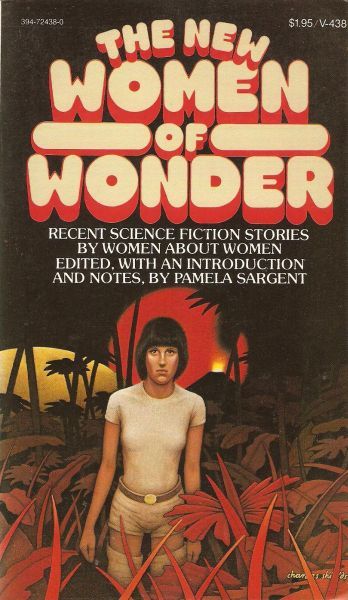

New Women of Wonder (Women of Wonder, volume 3)

By Pamela Sargent

7 Mar, 2015

0 comments

1978’s The New Women of Wonder was the third volume in the series. Until 1995, when the fourth volume Women of Wonder: the Classic Years was released, this was the concluding anthology in the Women of Wonder series. Unlike the first two volumes, New Women of Wonder focused entirely on contemporary (from the perspective of the late 1970s) works of science fiction by women.

A majority of the stories are also linked by an air of despair and hopelessness. They suggest that coexistence with men means at best subjugation, and at worst, much worse. How far we’ve come, eh?

Introduction (Pamela Sargent):

This twenty-two-page introduction, notably shorter than the first two introductions, focuses on the recent history of women in science fiction, a history that included a fair amount of resistance to the idea of expanding the domain of science fiction beyond the borders of so-called classic SF. As Sargent says:

Work that attempts to be innovative is seen as suspect.

This situation affects women and men who wish to attempt something new in their fiction. One author of a successful first novel had her second rejected by the same publisher because the book was about an all-female world and there were no male characters in it. Other authors have reported difficulties in seeing work published that defied conventional canons, either because of its style or because of its subject matter.

Some of this is to be expected (Although not appreciated) when one is writing in a “popular” genre and asking publishers, who have to show a profit, to print the finished work. Some of it may be the result of a growing conservatism in the society as a whole. Part of it, within SF, is that the audience is still seen as being largely male, much of it relatively conservative as well. Any difficulties an innovative or unconventional male author may face are multiplied for a female author. It is one of the paradoxes of science fiction as a whole that it is seen as “free-wheeling” and “speculative” while in reality it is so conservative.

I’ve stripped out the footnotes, but I will add that one of the footnotes supplies the information about the editor who rejected the second novel mentioned above. She was a woman and that the company in question is reported to have published books that would appeal only to men.

It’s depressing that you could take this essay, drop in a few new names, update a few references, and publish it today without robbing it of relevancy.

An interesting note: Andre Norton is acknowledged as an important author. Either something changed between 1966 when Lin Carter wrote the profile of Norton I referenced in my review of Secret of the Lost Race and 1978, when this was published, or Carter and Sargent were talking to different people.

“View from the Moon Station” (Sonya Dornan):

A short poem about the Earth as seen by an observer orbiting it.

“Screwtop” (Vonda N. McIntyre):

Kylis, interstellar vagabond, captured and sentenced to a long prison term by the justice system of the particularly doctrinaire world Redsun, is targeted for reproductive blackmail by the prison’s warden. Kylis is a stubborn woman, able to resist most pressures that warden can apply to her; unfortunately she has formed a triad with two other prisoners and they are Kylis’ great weakness.

The sad thing about this story isn’t that the government of Redsun uses the world’s comparative lack of resources to justify an abusive prison system, or that this all sounds so familiar. It’s that the abusive prison system of the story is still easier on its victims than is the US’s current prison-industrial system.

“The Warlord of Saturn’s Moons” (Eleanor Arnason):

Arnason contrasts the rather C.L. Moore-ish science fiction adventure story her protagonist is writing with the protagonist’s somewhat unrewarding life.

This seemed a bit downbeat until I read the next few stories.

“The Triumphant Head” (Josephine Saxton):

A woman labouriously assembles herself for the coming day, using every bit of artifice at her command to present an acceptable face to the world.

“The Heat Death of the Universe” (Pamela Zoline):

A housewife, struggling to keep her household functioning despite the entropic efforts of her kids and husband. This is, of course, futile; not only will her work go unappreciated, but, in the end, entropy always wins.

“Songs of War” (Kit Reed):

Women rise up to form a revolutionary army in an attempt to end their exploitation at the hands of society and their significant others; the men whose behavior inspired the revolution are baffled, incapable of seeing what it was that they did wrong. Like all attempts to improve society, the movement is soon commandeered by violent extremists, forcing the rank and file to choose between embracing ideological atrocity or slipping back on their old shackles.

The nice thing about this story is that the collection cannot possibly get more downbeat.

“The Women Men Don’t See” (James Tiptree, Jr.):

A male explorer accompanying a mother and daughter in the wilds of central America is taken aback when he sees the two women escape the strictures of a male-dominated society. Even though that society doesn’t particularly value either woman, the idea the women would want to pursue goals unrelated to that society is a strange and baffling concept for him.

You know, as tempting as it is to go for the cheap shot of pretending this is even more depressing than the Reed story, at least in this story the mother and daughter are offered something better than a choice between old ways known to be exploitative and new ways that turn out to be worse. The option the women seek out and accept isn’t any worse that what waits for them back home.

“Debut (Carol Emshwiller):

A young woman, raised for a very special purpose, finally is sent forth to her futuristic cotillion.

I suppose technically cotillions have more than two dancers involved. The society in this seems to be functional enough, but it achieves that through what amounts to sexual segregation.

“When it Changed” (Joanna Russ):

A perfectly functional world that long ago adjusted to the total extinction of men due to a gendercidal plague is finally contacted by a galactic civilization that is male-dominated and disinclined to allow the women to continue to go their own way.

This might be more hopeless than the Reed: nothing good women do can survive even a little contact with men, because men will appropriate what they don’t ruin. Isolation itself is not enough; secrecy is also required because otherwise the men will track the women down.

“Dead in Irons” (Chelsea Quinn Yarbro):

A young woman working on an interstellar passenger ship discovers the entire system is corrupt, that she is expected to have sex with her boss, that the passengers face slavery, and that refusal or attempts to reform risk a violent death. Then it gets worse.

I think I first read this in a Jack Dann anthology called FTL and I know it is inextricably tangled in my mind with a short story whose final line is “Look, baby! Food!”

“Building Block” (Sonya Dornan):

A space-architect struggles with creative blocks and intellectual appropriation.

I don’t have much to say about this except it wasn’t as bleak and depressing as most of the previous stories.

“Eyes of Amber” (Joan D. Vinge):

Deposed aristocrat turned bandit and assassin T’uupieh is positively gleeful to learn that her next contract is the usurper who seized her family’s estate. The assassin’s pet demon is less gleeful. This is because the supposed demon is an American lander, T’uupieh is an alien living on methane-shrouded Titan, and the voices that emerge from the demon are those of humans back on Earth. These humans are dependent on their Titanian ally’s aid in their research project, but are in no way keen to be involved, no matter how passively, in brutal murder.

You don’t see a lot of SF where humans are limited to exploring other worlds remotely but this would be one of that handful. Vinge also avoids the shortcut whereby the probe is an autonomous AI; this one is just an unthinking machine and not only the humans doing everything remotely, they are doing it with a substantial time lag.

This is very much a pre-Voyager Titan. There was a fashion around this time for nostalgic anthologies celebrating outmoded visions of the worlds of the old pre-space probe solar system. Space probes revealed what the other bodies of the Solar System were really like, but sometimes that was not as much fun as what we used to imagine (Martian canals, etc.). As far as I know, nobody ever bothered to gin up a Titan anthology, despite the fact that our conception of it has changed dramatically in the last forty years.

Despite the unpleasant social system on Titan and the disappointment on Earth about shortcomings [1] in their space programs, this story ends on a positive note. Probably a good choice on the part of the editor: put the strongest, most upbeat story at the end of the anthology.

Further Reading:

This is exactly what it says.

Even in 1978, when this collection was published, a number of these short stories were acknowledged as important works. Looking back from 2015, I can see that this anthology is jammed with classics. It‘s a real shame that this work is out of print. However, some of its stories are available in more recent books:

“The Warlord of Saturn’s Moons” can be found in Eleanor Arnason’s Ordinary People.

“The Triumphant Head” is included in Josephine Saxton’s The Power of Time.

“The Heat Death of the Universe” is included in The Wesleyan Anthology of Science Fiction, as is Russ’s “When It Changed.”

“Songs of War” is contained in Reed’s collection, The Story Until Now: A Great Big Book of Stories.

“The Women Men Don’t See” is included in the Tiptree collection Her Smoke Rose Up Forever.

“Debut” is included in The Collected Stories of Carol Emshwiller, Vol. 1.

1: There’s a rule I used to call The Niven Rule but which I just now have decided to call the Rusting Bridges rule. It came to me after reading Niven’s “All The Bridges Rusting.” In this story, humans have by the early 21st century explored the Solar System and sent not just one but two crewed ships to Alpha Centauri … despite which the characters moan endlessly about the dire state of the space program. “Eyes of Amber” would be another example of the Rusting Bridges Rules: No matter how much the space program you actually have has achieved, whether it’s first contact with aliens or trips to nearby stars, it can never have achieved as much as the space programs you can imagine would have achieved in its place, given that imaginary programs aren’t limited by issues of politics, funding, or engineering.