A Defector of a Kind

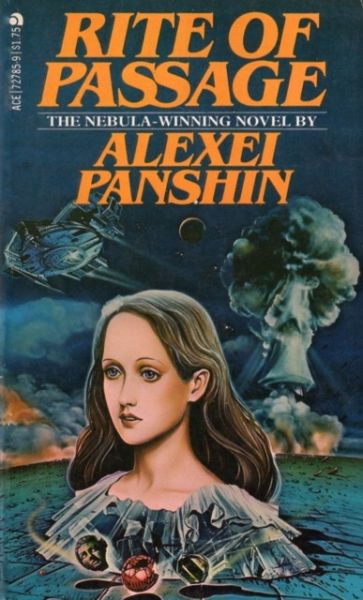

Rite of Passage

By Alexei Panshin

21 Jul, 2019

Alexei Panshin’s 1968 Rite of Passage is a standalone SF novel. It won a Nebula Award and was nominated for a Hugo.

Mia Havero grew up on a great Ship, an asteroid-sized vessel that wanders from star to star. It’s all she’s ever known. Mia’s Trial, a mandatory test that winnows the unfit from the fit, is approaching. If she passes, she will live out her life on her Ship. If she fails, she might be exiled. Or dead.

Mia Havero is twelve, going on thirteen.

Built before Earth’s destruction to transport the ancestors of the mudeaters to the filthy worlds where they grub out a meagre living, the Ships were re-purposed by their crew to serve as star-faring repositories of humanity’s legacy. Aware of the gravity of their position, the Ships carefully sequester their know-how, granting the mudeaters just enough hi-tech goods to obtain from the mudeaters the supplies the Ships need to survive. The Ships have preserved the best of old Earth. Why, under their benevolent management, the number of colony worlds has declined from one hundred twelve to about ninety!

A central part of the Ship ethos is a determination not to repeat Earth’s mistakes. Overpopulation doomed the Earth. Therefore the Ship carefully regulates its own population. Although wealthy by the standards of the colonial worlds, the Ship’s culture is not soft or merciful. People who want to remain on the Ship must meet its exacting standards or be consigned to life as a mudeater.

Trial is quite simple: armed with a simple but effective toolkit, teens are covertly dropped on whatever colony world happens to be handy (which world has been selected is kept secret from the teens, the better to test them). The teens must fend for themselves for a month. If they are still alive at the end of the month, they can activate their signal, at which point they will be retrieved from the planet.

Life pre-Trial is stressful. A sudden romance with fellow tween Jimmy provides a welcome distraction. Too bad the pair argue just before their Trials; rather than teaming up, Mia and Jimmy are dropped on the planet Tintera to face the challenges alone.

At first, Mia has no trouble surviving. This changes as soon as she meets the human Tinterans, who loath Shipfolk and who have no trouble recognizing Mia’s accent. In short order, she is given a beating and loses all of her advanced gear. She is lucky not to be thrown in prison or killed out of hand; even more lucky in that a kindly colonist named Kutsov takes her in.

The Tinterans have many habits Shipfolk find indefensible. Not only are they inexplicably hostile to Shipfolk, they have enslaved the local losels. Most alarmingly, the planet’s autocratic rulers permit unrestricted breeding. Tintera is a collection of behaviours seemingly designed to inflame Ship outrage. Still, Kutsov seems decent enough.

Jimmy was not as lucky as Mia. He is in a local jail. Mia isn’t the sort of girl to abandon her boyfriend to mudeater mercies. She breaks him out of jail, recovering some of their equipment in the process, as well as a crucial bit of information: the Mudeaters somehow managed to capture a scoutship, which they plan to use to attack the Ship.

It’s up to the teens to save their home.

~oOo~

The story is told from Mia’s point of view. While it takes her some time to notice the flaws in her society, the text makes them pretty clear. To begin with, this is a society that orchestrates matters so that a certain fraction of its kids die completely avoidable deaths, thus ensuring that the survivors are highly motivated to value what they have. As well, not only has the Ship habit of hoarding most of humanity’s knowledge for themselves allowed some of the colonies to dwindle and die out, but from time to time worlds have been morally disciplined, that is, scoured clean of life, for vexing the Ships.

On top of all that, while the Shipfolk may be rich and highly educated, they are uncreative. Not all that surprising, since they didn’t create the wealth and knowledge they claim for their own. They preserve and aim at stasis. All they’ve managed is an inflexible, priggish, homicidal system wherein little changes on the Ships, while the colony worlds are trapped in poverty and decline.

Unsurprisingly, a lot of the Shipfolk have convinced themselves that they are doing the colonies a favour by denying them access to Earth’s heritage. This is not a universal belief; a large part of the novel centres on the political struggle between the two sides. There is some pretense that both sides have a point but when one comes down to it, only one side is in the habit of committing planetary genocide out of pique and it’s not the folks who want to share the wealth.

Many authors might have had their heroic lead shame her elders into reconsidering their ways. Not Panshin. Mia’s elders are firmly in control and see no reason why they should change a system that serves them well. Mia does her best to bring about reform but fails (at least in the context of this novel [1]). That’s a bit of a downer, although the failure does give Mia some life goals.

A lot of authors have tried to write Heinlein style juvenile SF novels. Panshin’s effort is one of the few that works.

Rite of Passage is available here (Amazon), here (Amazon.ca) and here (Chapters-Indigo).

1: There is a happy ending, of sorts: there is a story that links Mia’s Ship-dominated era with the Anthony Villiers period. The Ships are most definitely not running things by Villiers’ time.