A Game of Ghosts

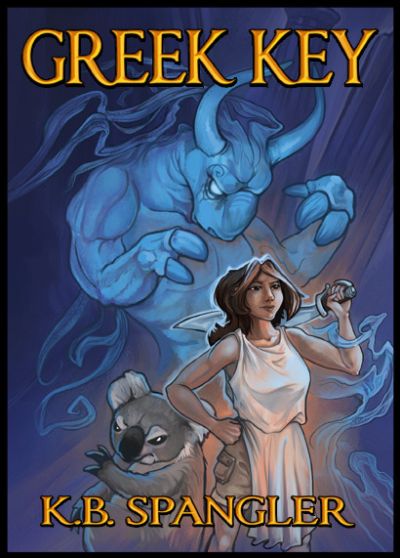

Greek Key

By K B Spangler

31 Oct, 2015

0 comments

K. B. Spangler’s 2015 Greek Key sends a trio of odd characters on a quest to discover the origins of the Antikythera Mechanism (a real-world artefact that featured in a subplot of an earlier Spangler book, State Machine). The cast of characters includes:

- Mike Reilly, the World’s Worst Psychic,

- Hope Blackwell, World’s Second Worst Psychic, previously met in A Girl and Her Fed),

- and a talking koala named Speedy.

Hope is well connected, rich thanks to her connections and a talented martial artist. She has one quirky ability that makes her particularly useful when it comes to tracking down the origins of an ancient, technologically anomalous device: Hope can talk to ghosts.

The Mechanism is an analog computer, purpose unclear, that is more than two thousand years old. Experts think that it might have been made by Archimedes, or possibly Posidonius. The experts might be wrong, and Hope and company might be on the wrong track as they search for links between Archimedes, or Posidonius, and the Mechanism— but the fact that series villain Hanlon’s goons keep mounting ineffectual attacks on the trio suggests that at least Hanlon thinks there is substance to their investigation.

Hope’s ability to talk to ghosts is severely curtailed outside of the US (cultural barriers seem to be the medium’s kryptonite), but there are other ways to pass information from the dead to the living. Hope finds herself reliving in dreams episodes from the life of a Greek woman who lived a thousand years before Archimedes and Posidonius, arguably the most famous Mycenaean Greek of all: Helen of Troy. (OK, maybe she is just myth, but we’re assuming that she was a real woman, for purposes of plot.)

Helen has a very specific task in mind for Hope and her two pals, one that will take the trio to an island beyond the ken of mortals, there to face a monster literally straight out of myth.

~oOo~

I was impressed by how badly Hanlon briefs his minions. You’d think it would be more cost-effective to give goons a heads-up that their targets are two martial arts adepts and a killer koala, rather than sending an unending stream of surprisingly fragile thugs to be beaten up, or worse. Even if you’re hiring thugs in bulk, the cost has to mount up. If I was one of Hanlon’s goons, I would definitely file a grievance with the union over the lack of adequate briefing.

While I was familiar with the Mechanism subplot from State Machine, I still have not read the A Girl and Her Fed webcomic. I was a bit worried that the plot of this novel would depend on some familiarity with that work. Turned out that I didn’t need to be worried; I was able to figure out who was who and how they relate to each other. Even though the information was dispensed by Hope, who has all the placid clarity of purpose of an amphetamine crazed squirrel,

I didn’t really warm to Hope, She seems to be disgustingly awesome at everything except staying focused. But that didn’t matter much. The true foci of this novel are Helen of Sparta and Theseus, King of Athens. I found the focus on Helen particularly interesting. Until I read this book, I had not realized how thoroughly my schooling had taught me an impoverished, bowdlerized version of Greek mythology. Helen was reduced from a woman with her own complicated history and aspirations to a mere trophy for men squabble over. Most of what I now know about the mythical/real Helen I know because this novel inspired me to go looking.

Thirty-two centuries having passed since the era recalled by the Homeric tale of the Trojan war. Later writers (Greek, Roman, Western) have elaborated on the sparse details found in the Iliad. Spangler could choose from a wealth of often very contradictory material. Sources differ even on such quotidian details as Helen’s parentage. Spangler has painted Helen as a well-born woman in a society where aristocratic birth makes her valuable but not necessarily powerful. Helen gains some power because she is cunning and ruthless. Ruthless even as a ghost; to Helen, Hope is just a means to an end. A expendable means.

There are ghosts in this story, but no gods. The meddling deities of the Illiad play no overt role here. What we see instead are gritty Bronze-age politics, complicated by functional magic. Specifically, curses that have accrued enormous power over three millennia.