A Little Bit Dangerous

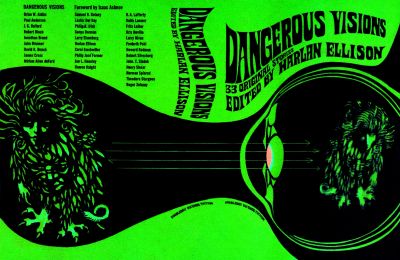

Dangerous Visions (Dangerous Visions, volume 1)

Edited by Harlan Ellison

20 Oct, 2024

1967’s Dangerous Visions was the first volume in Harlan Ellison’s Dangerous Visions anthology series.

Ellison’s purpose in editing this anthology was to eschew hoary old taboos, celebrate the full potential of speculative fiction, and carve out a bit of the New Wave as his very own1. To this end, he recruited a small army of authors, purchased a huge number of words, and produced this hefty volume.

How does Dangerous Visions hold up after fifty-seven years?

First, a world about the price. My copy is the 1972 Berkley Medallion mass market paperback.

On its cover, to the upper right of the frankly generic cover art: $1.50. This is considerably more expensive than the 75 to 95 cents mass market paperbacks used to cost back then. Presumably this was due to the book’s unusual length — 576 pages2. Nevertheless, were we to tolerate outrageous prices like a dollar fifty, where would it end? Two bucks a book? Being frugal, I purchased my copy used for 75 cents.

Second, I’ve been dreading rereading this book since a reader commissioned a review. My reading speed seems to have slowed and 576 pages is daunting. But as it turned out, this brick is a quick read. I read the whole thing, cover to cover, in a single evening.

Third, one might very reasonably expect Ellison to have crammed his anthology full of young Turks like himself. In fact, authors who debuted in the 1930s and 1940s are well represented; the largest cohort is authors who debuted in the 1950s. Not terribly surprising, as I’ve read complaints from such steadfastly conventional SF authors as Gordon R. Dickson about the limitations to which they were subjected by publishers’ editorial staff at this time. There were lots of SF authors desperate for a chance to stretch their wings.

I also note that while twenty-nine of the thirty-two3 stories were written by men, Ellison does at least refer to the women as women and not girls or chicks. He claimed to have wanted at least one more story by a woman but was unable to secure it.

In addition to the stories themselves, Ellison adds much commentary. Whether or not one enjoys Ellison’s material depends on one’s tolerance for bombastic braggadocio. Almost all of the authors receive effusive praise, the main exception being Damon Knight. Ellison bore Knight a grudge because Knight, having purchased a Kate Wilhelm story for inclusion in then some as yet unpublished anthology, selfishly refused to release the story so Ellison could include it in Dangerous Visions. More on Knight later.

In addition to introductions and afterwords, the stories are accompanied by black and white illustrations that are poorly reproduced in the MMPB.

The anthology is a bit of a mixed bag. There are award winning classics in here. DV definitely passed the “Did James remember the story simply by looking at the table of contents?” test. There are also a number of duds, not to mention competent but extremely minor stories whose inclusion makes one wonder what Ellison was thinking. The better stories tend to be the ones I remembered as soon as I saw the title (also, the ones more likely to have been reprinted in other anthologies and collections), while the ones I forgot I forgot for a reason.

This anthology could have been shorter and even stronger, [sarcasm] a finding that I am certain is in no way a harbinger of things to come [/sarcasm]. Nevertheless, I think it is still worth readers’ time, and not just as a time capsule of the SF of yesteryear.

Dangerous Visions is available here (Amazon US), here (Amazon Canada), here (Amazon UK), here (Apple Books), here (Barnes & Noble), here (Chapters-Indigo), and here (Words Worth Books).

Foreword 1‑The Second Revolution • (1967) • essay by Isaac Asimov

An Asimov’s‑eye history of SF.

Foreword 2‑Harlan and I • [Asimov’s Essays: Other’s Work] • (1967) • essay by Isaac Asimov

An Asimov’s‑eye view of Harlan Ellison.

A relevant detail that emerges from Asimov’s commentary and Ellison’s reaction to it is that it is entirely possible for someone with whom Ellison has interacted to remember the event as Ellison being an abrasive asshole, whereas Ellison remembers himself in a far more favorable light. See also my review of Space War Blues.

Thirty-Two Soothsayers • (1967) • essay by Harlan Ellison

Ellison explains his purpose in crafting this anthology. Also included, some diverting details on the economics of assembling a project of this magnitude.

While it requires a nigh-Herculean effort to avoid bitchy commentary when reviewing this anthology (thanks to later events), Ellison was trying to accomplish something substantial with Dangerous Visions. This isn’t some hastily assembled themed anthology, but a project into which considerable effort was poured.

“Evensong” • (1967) • short story by Lester del Rey

Misplaced charity ends badly for a powerful being.

An odd choice for the first story, as it covers ground already covered by del Rey in his 1954 For I Am a Jealous People!

“Flies” • (1967) • short story by Robert Silverberg

This is a short story by Robert Silverberg.

“The Day After the Day the Martians Came” • (1967) • short story by Frederik Pohl

The pitiable Martians cannot offer humans advanced philosophy or super technology. They provide something even more valuable: a group all humanity can unite in despising.

At least none of the humans in this story decided to kidnap Martians to put them on display on Earth.

Pohl eventually got a whole book out of his Martian cycle. Not bad, given that the Mariner exploration project made the existence of actual Martians inconceivable.

Riders of the Purple Wage • (1967) • novella by Philip José Farmer

A young man living in the welfare-supported Great Society of tomorrow struggles to carve out a meaningful life for himself, despite the very real option of simply embracing lazy decadence.

I hate this story when I first read it in one of Asimov’s Hugo Winner anthologies. Since then, I’ve gone back and forth about how I feel about it. At this moment, I find it most interesting as a testament to how Americans thought the Great Society might develop.

“The Malley System” • (1967) • short story by Miriam Allen deFord

A novel cure for violent offenders offers many benefits… or might if it worked.

“A Toy for Juliette” • (1967) • short story by Robert Bloch

A kindly old man uses a time machine to provide his homicidally sadistic granddaughter with all the victims she could want. One too many, in fact.

The Prowler in the City at the Edge of the World • (1967) • novelette by Harlan Ellison

In this sequel to the Bloch story immediately above, Jack the Ripper discovers that the banquet of easily murdered degenerates with which he finds himself presented is less satisfactory than he first believed.

“The Night That All Time Broke Out” • (1967) • short story by Brian W. Aldiss

A temporal industrial mishap causes widespread calamity.

“The Man Who Went to the Moon – Twice” • (1967) • short story by Howard Rodman

An old man clings to old fame as he struggles against irrelevance.

Well, this certainly has no personal relevance.

Faith of Our Fathers • (1967) • novelette by Philip K. Dick

A Chinese functionary in a China-dominated world is confronted by the worst sort of drug trip, the sort that ends and reveals reality in all its alarming detail.

“The Jigsaw Man” • [Known Space] • (1967) • short story by Larry Niven

An exploration of how far people will go in search of affordable health care.

Niven makes it clear that not only does he think this organ-bank world is plausible, he thinks it is virtually inevitable.

Gonna Roll the Bones • (1967) • novelette by Fritz Leiber

A gambler is displeased to discover the truth behind his evening of gambling.

This would be the obligatory “Wives: bitches or what?” story. This could be a running theme with stories of this vintage. Ellison, in his commentary elsewhere, underlines the misogyny with an anecdote about an ex-wife.

“Lord Randy, My Son” • (1967) • short story by Joe L. Hensley

A retarded boy like Randy would normally be the subject of pity and abuse… but Randy has some unique abilities. His neighbors have learned to be cautious.

I liked this when it was “It’s a Good Life” by Jerome Bixby.

Eutopia • (1967) • novelette by Poul Anderson

A researcher’s foray into alternate history is cut short by cultural differences with his hosts.

This is the story in which the big twist is that the sympathetic leader from an otherwise admirable timeline is a boy-hungry homosssssssssexual. Anderson finds other, very Anderson-ish, reasons to critique the scholar’s home timeline while praising the homicidal Vikings from whom the scholar is fleeing.

“Incident in Moderan” • [Moderan] • (1967) • short story by David R. Bunch

A pitiable all-flesh human woefully misunderstands a gleefully militaristic cyborg.

“The Escaping” • [Moderan] • (1967) • short story by David R. Bunch

Another cyborg explains at length the amusing trick it will play on its enemies.

Yeah, I don’t know why there are two Moderan stories. This probably means I should finally review that David R. Bunch collection that’s been gathering dust, to see if I can work out what the appeal might have been.

“The Doll-House” • (1967) • short story by James Cross

A financially-strapped man is offered the means for prosperity, if only he can avoid bungling the opportunity.

The suspense in stories like this isn’t if he will screw up, but how he will screw up. OK, yeah, there’s probably a very few stories about the protagonist somehow prevailing despite himself, but that’s not the way to bet.

“Sex and/or Mr. Morrison” • (1967) • short story by Carol Emshwiller

Unrequited infatuation frustrates.

“Shall the Dust Praise Thee?” • (1967) • short story by Damon Knight

Where God went wrong, oddly not by Oolon Colluphid. Actually, there are enough Where God Went Wrong stories out there to fill an anthology; I could snag two from this anthology alone.

Ellison’s comments about Knight are astonishingly graceless, even for Ellison. Knight is described in terms like “totally bewildered and bursting into tears,” “sulking for two days,” and “spoilsport.” Ellison asserts that Knight himself was only included to end Knight’s interminable whining to Kate Wilhelm about how she was invited but Knight was not. Such grudging complements Ellison feels compelled to provide are backhanded at best.

It’s possible I am too literal minded to get the joke, but it sure reads as if Ellison were serious.

If All Men Were Brothers, Would You Let One Marry Your Sister? • (1967) • novella by Theodore Sturgeon

What dread practice makes an otherwise Utopian society a galactic pariah?

No spoilers, except to say that Heinlein would be very happy to learn the forbidden basis for a happy society.

“What Happened to Auguste Clarot?” • (1967) • short story by Larry Eisenberg

The secret but assuredly true tale of how Auguste Clarot met his well-earned demise.

“Ersatz” • (1967) • short story by Henry Slesar

A soldier discovers to his horror just how encompassing wartime shortages are. The woman he is chasing turns out to be a cross-dressing man.

Is Rowling looking for stories for an anthology?

“Go, Go, Go, Said the Bird” • (1967) • short story by Sonya Dorman

A resourceful cavewoman is very nearly equal to the challenges that will confront her.

“The Happy Breed” • (1967) • short story by John Sladek

The wonderous Machines liberate humanity from every possible ill, leaving humans to enjoy life with folded hands.

“Encounter with a Hick” • (1967) • short story by Jonathan Brand

Genesis retold as a zany account.

It would also be pretty easy to assemble a collection of stories with same basic idea as this one. Much harder to find enough good stories to make a book worth reading.

“From the Government Printing Office” • (1967) • short story by Kris Neville

A perfectly reasonable infant is confounded by the bizarre ways of adults.

“Land of the Great Horses” • (1967) • short story by R. A. Lafferty

Alien researcher will return appropriated study material… at a price.

“The Recognition” • (1967) • short story by J. G. Ballard

Bucolic tranquility is interrupted by the arrival of a most curious circus.

Is the arrival of a most curious circus ever good? Why do people insist on attending them?

“Judas” • (1967) • short story by John Brunner

An attempt to liberate humanity from its robo-messiah produces unfortunate results.

Test to Destruction • (1967) • novelette by Keith Laumer

Caught between autocratic oppression and an invading alien fleet, a determined man finds his true potential.

There’s a bit about scale in this story that also turns up in a passing anecdote in The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy. Surely that has to be a coincidence?

“Carcinoma Angels” • (1967) • short story by Norman Spinrad

A confident self-made man sets out to cure himself of terminal cancer, with mixed results.

Spinrad is often exceedingly unsubtle, despite which as a teen I managed to overlook evidence suggesting that our hero is an enormous jerk and that his eventual circumstances are not a cruel twist of fate but well-earned comeuppance.

“Auto-da-Fé” • (1967) • short story by Roger Zelazny

Man versus automobile in the arena. Which will prevail?

Even minor Zelazny, of which this is a sample, is skillfully polished. There’s not much dangerous about this, even by the standards of 1967.

“Aye, and Gomorrah…” • (1967) • short story by Samuel R. Delany

A bold technical fix for the challenges of space travel makes spacefarers the focus of unsavory terrestrials with sexual fixations best left undiscussed.

1: Ellison takes pains to underline that his new thing is different from Judith Merril’s new thing and Michael Moorcock’s new thing. I’ve reviewed Merril’s. I should track down something analogous from Moorcock. Any suggestions?

2: Berkley’s MMPB of Heinlein’s The Past Through Tomorrow had a similar price for similar reasons. The two share something else… they’re falling apart. Other Berkley MMPBs of this vintage are not. My guess is that the MMPB binding of this era (or at least Berkley’s) was not quite up to books of this length.

3: Thirty-two according to the book’s text, thirty-three according to the cover.