A forgotten Canadian classic

The Garden

By Jasper MacDonald King

11 Nov, 2015

0 comments

Canadian author Jasper MacDonald King was, in his day, a bestselling author of children’s fantasy. In recent years, certain “politically correct” critics have chosen to ignore his delightful fiction and focus on aspects of his life that were admittedly regrettable — the letter to his distant cousin the Prime Minister urging that the St Louis be turned away, his participation in the Orange Order’s annual “flogging Catholics through the streets” celebration (the use of an actual Catholic was discontinued in 1978, I might point out) and his status as the last person to be hanged in Canada (following the discoveries in his garden and a sensational 1952 trial ) — but surely these are mere distractions from the undeniable truth that he wrote some jolly good books. Whatever his life and opinions may have been, surely his fiction can be enjoyed for what it is.

Of all King’s books, none is more beloved than 1938’s The Garden.

The Garden is set in the 1890s, during the brief prime ministership of John Sparrow David Thompson. Thompson, being a Catholic (or “filthy Papist degenerate,” as King puts it in his quaint vernacular), has handed the reigns of power to his co-religionists. All across Canada, sinister priests and nuns run amok.

The Meighan twins, Bobby and Betty, “as white and pretty as a Canadian snowfall,” live in a Toronto that is increasingly Irish, French, and Italian. For the moment, the purity of their Anglican faith keeps the dusky Catholic rabble at bay, but the children fear that one day their faith will fail and they will be assimilated by the filthy horde.

But before that can happen, they meet the Gardener, a man who offers them sanctuary in his walled garden. Soon all three are working together to stem the Catholic tide. With the help of the plucky children, the Gardener identifies the linchpins of the papist conspiracy. One by one the papists are lured into the Garden, where each of them meets a suitable finale. When the final cultist dies, their dread master the Prime Minister drops dead in mid-meal in Windsor Castle and Canada is saved.

~oOo~

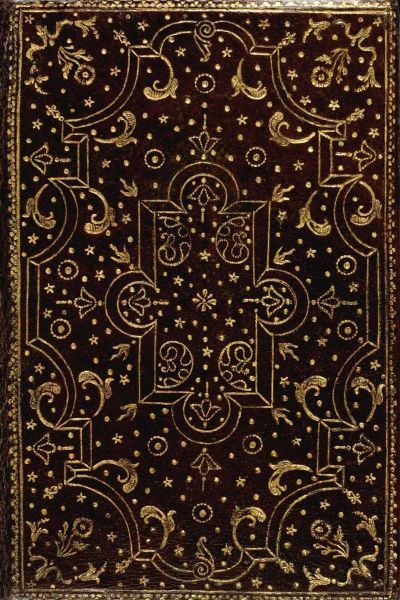

No review of The Garden can be complete without a mention of the original illustrations, which were drawn by Reggie and Margaret “Tigs” Brown, the children on whom the Meighan twins were based. By all reports, the Brown children and King were very close; it may have been that fond sentiment that explains why the siblings were eventually found buried in King’s garden. The Brown family no longer allows publishers to use the children’s illustrations, which I think is a real shame.

Perhaps the most thrilling sequence in the book ensues after the sinister Mary O’Neill escapes from the stone cell under the garden shed. She very nearly reaches the nearest police station, which the unnamed narrator assures us was “a nest of the vilest sort of foreign muck.” Nobody could fail to enjoy the dramatic chase through the poorly lit streets and the climactic fight, as the children and their mentor face off against “a witch armed with the deadliest of Catholic spells.” The plucky Protestant trio is armed only with the most mundane of sharp-edged gardening tools.

A few shrill agitators would like to distract us from the enduring qualities of the book by focusing on the admittedly regrettable fact that the entire book is based on the twelve murders a much younger King and his friends the Brown twins committed between 1892 and 1894. What these people forget is that anti-Catholic feelings were traditionally quite common in Canada—the Orange Order lost control of Toronto only comparatively recently, with the election of Nathan Phillips — and King’s views are really only unusual in the vigour with which he expressed them, not for their content. He was, in the end, merely a man of his times. Surely enough years have passed since his youthful follies that we can ignore them and focus on the texts. As many fans and acolytes would testify, unlike his victims, Jasper MacDonald King’s fiction will live on forever.