A simple, daring plan which at practically every stage was packed with things that could go wrong

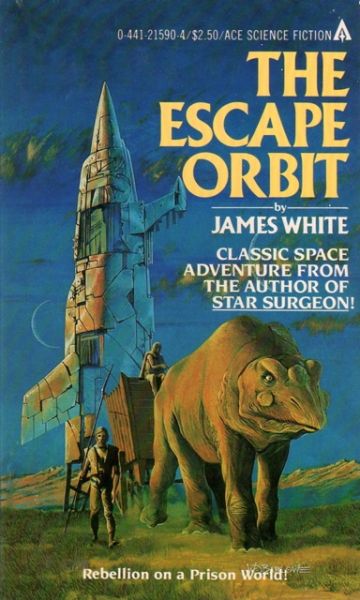

The Escape Orbit

By James White

14 Feb, 2015

0 comments

I was very excited to be commissioned to review this novel. White is one of my favorite authors. Even his Sector General stories, which are not my thing, get points for having plots driven by something other than violence. Not only that, but this is one of the few James White novels that I had never read. What could go wrong?

Well, two things. First, 1965’s The Escape Orbit is as close to MilSF as White ever got. Second, there is one thing about White’s fiction that I often find troublesome. Unfortunately for me, that one thing is front and center in this novel.

Perhaps, in a better time, humanity and the chlorine-breathing Bugs could have learned to co-exist. In a worse time, they would have just ignored each other (it’s not like either species can use the other’s real estate). Alas for humanity and the Bugs, they met at just the wrong time, when well-intentioned good will could only lead to tragedy. What began as attempts to bridge the vast gulf between Bug and human ended in violence. Each side found the Other profoundly disturbing. The humans evinced a hair-trigger readiness to take offense. Random eruptions of violence spiraled into a particularly pointless war.

War drags on for almost a century, grinding both sides down. Because both species are essentially civilized beings, Bugs and humans capture prisoners when possible. Because communication between the two powers is almost impossible, there is no way to return the POWs to their people. For humans, the Bug POWs are a growing and increasingly intractable problem. The Bugs, in contrast, have come up with an ingenious and humane solution.

Captured with the rest of the survivors of the starship “erroneously named Victorious,” Warren discovers what exactly the Bugs do with their POWs when he and his companions are dumped on a habitable world within the Bug sphere of influence. The chlorine-breathing Bugs have no use for Earth-like worlds. By settling such worlds with human POWs they free up all the Bug personnel who would be otherwise occupied with guarding and taking care of the humans. While the prisoners are given enough equipment to establish a primitive agrarian way of life, they are well short of having the technology necessary to construct rockets. A single ship with a handful of Bugs on board is all that is needed to patrol a world full of prisoners.

By the time Warren is dumped on the prison planet, the POW society has been established for quite some time, long enough for two distinct factions to have formed. The so-called Civilians, by far the largest faction, believe that escape is impossible and that, as far as the prisoners are concerned, the singularly pointless war is over. The only sensible thing to do is to settle down to colonize what is, after all, a reasonably friendly world. The Committee, in contrast, believes it is the duty of every military person to plot escape. The fact that the Committee is continually losing members to the Civilians only makes the dwindling Committee that much more fanatical. Warren suspects that this dynamic will soon lead to open conflict between the well-organized Committee and the numerically superior but disorganized Civilians.

Warren opts to join the Committee, for reasons that will be apparent later. The upper ranks of the Committee are first pleased to gain a new recruit — then disconcerted when they learn that Warren is no mere captain, as they assumed, but rather a Sector Marshal. He is by far the most senior officer on the planet and, by right of rank, the man in command of the Committee. He quickly sets about dealing with the impending conflict.

The Committee has an escape plan. It has had the same escape plan for the better part of a generation, because, somehow, it has never seemed the right time to activate the plan. Warren sets a firm deadline for the Escape (an attempt to convince the orbiting patrol ship that one of their own vessels has crashed on the planet, necessitating a rescue attempt that will, the humans hope, allow them to commandeer the patrol ship). There are only three years to go before Warren’s deadline. Warren uses the looming deadline to completely reshape the prison planet’s society.

Can a community limited to the most basic agricultural equipment manage to use what amounts to bamboo technology to overcome enemies with access to modern weapons? Can one man maneuver legions of subordinates in accordance with a grand strategy he shares with no-one else? And given that the war is being fought for reasons even Warren thinks are specious, why is he so determined to get off the planet to rejoin the conflict among the stars?

People who read my review of Monsters and Medics will recognize the basic set-up here as one White previously used in the 1959 short story “Dogfight.” In “Dogfight,” it was the humans who hit on the idea of dumping their alien enemies on empty planets; in this book, it is the aliens who adopt that comparatively humane (or whatever the applicable Bug word is) solution to their POW problem.

It’s typical of White that he would make it clear up front that the grand conflict between two interstellar empires is at its heart stupid and inglorious, a war that shows the humans, at least, as petty and spiteful. In the Bugs’ defense, it’s not clear to me from the text that the Bugs have the sort of psychology that leads to mass violence. The incidents of the sort that sparked the war that we are told about are human-on-Bug attacks. From the Bug point of view, the War may be an entirely defensive one.

Humans do not come off particularly well in this novel. Warren is not only repelled and annoyed by those around him, but, being more self-aware than that fellow over in The Bridge on the River Kwai, he loathes himself for the way in which he treats the people around him. This book was somewhat shorter on likable characters than I expected from a White narrative (and that’s taking into account that one of White’s long-running characters over in Sector General is more abrasive than House [1]).

Which gets us to the specific problem I had with The Escape Orbit, which is the matter of James White and women.

Over the course of his career, White’s views on women appear to have evolved from an affectionate contempt I will politely call “rampant male chauvinist piggery,” as exemplified in 1957’s “The Lights Outside the Windows,” towards something more egalitarian. This book falls somewhere in the middle of the spectrum. White seems to have been trying to be more even-handed without quite having the ability to carry that off.

The great advantage the Civilians have over the Committee is that women tend to defect to the Civilians at a higher rate than the men, due to what the author sees as their inherent desire to settle down with a husband and children [2]. The Committee’s response to this is to single out the few women still within their ranks as probable traitors, who are to be given only the most unimportant and unpleasant tasks. This policy serves to contain the damage the women might do while ridding the Committee of the future traitors as quickly as possible. Fraternization between Civilian and Committee being frowned upon, this means that any men who want long-term female companionship are forced to defect to the Civilians.

To his credit, Warren sees that, not only is the Committee dooming itself to become an endlessly compressing sphere of masculine fanaticism, but that the He-Man Woman-Haters Clubhouse approach is also denying the Escape access to key skills possessed by women. The Space Navy is an elite force drawn from the best and most educated of humanity; that goes for the women in the navy as well as the men. For the Escape to succeed, the women (or at least some of the women) have to be part of the effort. Warren takes steps to stop the willful abuse of female staff, hoping to stanch the flow of Committee women to the Civilians.

Unfortunately, White gives us a good look inside Warren’s head. He is not as sexist as the other members of the Committee, but he is still sexist. Warren sees the necessity of recruiting women, but he doesn’t really trust them and he certainly doesn’t seem to respect them. They may be useful, but they are almost as inherently Other as the Bugs.

The telling scene falls on pages 128 – 130, for people with the 1983 Ace edition. Fielding, the senior woman on the Committee, complains of a series of sexual assaults. While her demand that something be done is supported by two of the male Committee members, Hutton and Hynds [3], another Committee ember (male) argues that the men involved in the Escape are experiencing a lot of stress and should not be denied whatever entertainment they can find. Yet another male asserts that the victims, some of whom sustained serious injuries, were asking for it. With his senior Committee divided on the question of what to do about the rapes, Warren comes down on the side of “they were asking for it, and men will be men.”

If I were a book-tosser, that would have been the moment the book hit the wall.

Now, Warren does have a grander vision than is immediately apparent (although one he admits does not reflect well on him). He is orchestrating the Escape because he has the long-term interests of Civilians, Committee, and humanity — even the interests of the Bugs — in mind [4]. I like a good story of Machiavellian machinations as much as the next person but every time I’d start getting immersed in the novel, the woman-question would come up and irritation would kick me out of the story. I like White’s books in general, but I don’t like this one. As much as it pains me to say this to my readers, I cannot recommend it.

1: Although, unlike House, Major O’Mara is not playing out a particularly depraved variation of Munchhausen’s by Proxy.

2:The characters or rather the men believe women have an inherent desire for husbands and children, and that all men want is sex. Interestingly, I am not sure if Fielding shares these views; her reaction early in to a comment of Warren’s suggests she does not and later when she propositions Warren, he discounts her sincerity.

3: In another scene, Warren tells Fielding that he thinks Hutton has a crush on her. It’s possible Warren thinks Hutton is supporting Fielding because he has the hots for her, not out of basic human decency.

4: I did wonder, from time to time, if this work was in any way influenced by H. Beam Piper’s Space Vikings.