And Had Some Fun

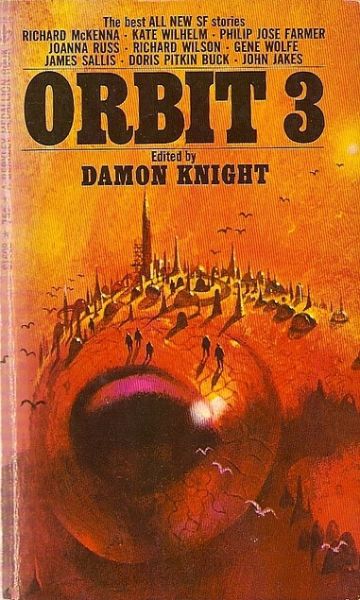

Orbit 3 (Orbit, volume 3)

Edited by Damon Knight

13 Jul, 2021

1968’s Orbit 3 is the third volume in Damon Knight’s eponymous science fiction anthology series.

This has interior artwork by Jack Gaughan that was, uh, there. I didn’t particularly like it, but I also didn’t actively loathe it.

There are nine stories by three women and six men (unless I miscounted, as I did in my last review). Many of the stories exemplify 1960s sexism.

Authors included are all white (at least by current standards: numerus clausus was of course in force at various US universities at least until the 1960s, so the ethnic categories into which authors could have been sorted would have been different when Knight assembled Orbit 3.) I have not looked through every volume after the third, but I don’t really expect a lot of POC authors to appear in later volumes. There may be none.

By this point stories in the series attracting attention and win awards. Two stories walked away with Nebula Wins and one of them got a Hugo nomination as well. While the golden years of Orbit are still to come, readers who encounter this volume may find it worth their time.

Orbit 3 is out of print.

Mother to the World • novelette by Richard Wilson

China’s surprising response to an American attack spares two humans from otherwise universal extinction: a man confident in his intellectual superiority and a woman he eventually comes to love despite her manifest cognitive inferiority1. This is all well and good for the moment … but who precisely are their children to marry?2

In the US’s defense, the first hint it had that China had a WMD capable of reducing the planetary primate population to dust was when the weapon was used. To quote: “Nobody’d suspected it of that relatively backward country which the United States had believed it was softening up, in a brushfire war, for enforced diplomacy.”

At the risk of spoiling a half-century old story: the only people available for future efforts to procreate are members of this family and there’s no last-minute miracle save.

Mother won the 1969 Nebula for Best Novelette and was a finalist for the 1969 Hugo for Best Novelette.

Bramble Bush • (1968) • novelette by Richard McKenna

Human explorers visit Proxima Centauri’s habitable world, curious why the nearest garden world to the Earth has never been explored or settled. They soon discover Proxima’s world is inhabited and that the peculiar perceptual abilities of the natives present a trap from which the visitors may never escape.

This is somewhat reminiscent of McKenna’s “Fiddler’s Green” in a previous Orbit, in that perception has measurable effects on reality.

The Barbarian • [Alyx] • (1968) • novelette by Joanna Russ

Alyx reluctantly partners for the moment with an obnoxious wizard who claims to have created the world in which Alyx and all those dear to her live. Although the cruel mage has a certain amount of proof for his claims, cunning Alyx spots a possible loophole. But will reality survive her bold test?

I assume that the Evil Warlock Manual has in large print an admonition never to ally with a barbarian and that no Evil Warlock ever reads that far.

Knight admits to a blind spot when it comes to women characters:

If Joanna Russ had consulted me before beginning to write her Alyx stories (see “I Gave Her Sack and Sherry” and “The Adventuress,” in Orbit 2), I would have told her nobody could get away with a series of heroic fantasies of prehistory in which the central character, the barbaric adventurer, is a woman. I would have been wrong, just as I was when I told Rosel George Brown she couldn’t sell a novel about a female private eye. [See Sibyl Sue Blue, Doubleday, 1966; Berkley, 1967 (published as Galactic Sibyl Sue Blue).]

Despite which he acquired the Alyx stories.

Russ was only about thirty when this was published, which may explain why thirty-four- or thirty-five-year-old Alyx is described as being on the verge of decrepitude.

“The Changeling” • short story by Gene Wolfe

Returned from war, a disgraced veteran finds time has transformed his home town, save for one very striking detail.

This is reminiscent of Ellison’s 1977 “Jeffty Is Five.”

Knight says:

I made a distinction between stories that make sense and those that mean something. I am unable to “make sense” out of this one — to make it add up neatly and come out even — but I strongly feel that it means something

Which sums up my feeling towards a lot of Wolfe. I don’t review his work because I either suspect I am missing the point or because (in the case of his last couple of books) the works are comprehensible because they are extremely subpar for Wolfe.

“Why They Mobbed the White House” • (1968) • short story by Doris Pitkin Buck

Frustrated with the complexity of US tax code, an activist is catapulted to national fame when he proposes offloading the preparation of tax forms onto supercomputers. Alas, he fails to foresee the effects on the supercomputers.

“The Planners” • (1968) • short story by Kate Wilhelm

A miserable, woman-hating psychologist who is plagued by a vivid imagination conducts research into intelligence amplification. His work does not make him happy.

Energetic loathing of women combined with desire for them is something of a recurring theme in this anthology.

This won the 1969 Nebula for Best Short Story.

Don’t Wash the Carats • (1968) • short story by Philip José Farmer

A surgical team is confronted by a baffling but potentially valuable discovery hidden within a patient.

“Letter to a Young Poet” • (1968) • short story by James Sallis

The autobiography of a space poet, delivered in the form of a rambling letter.

Here Is Thy Sting • (1968) • novelette by John Jakes

When Cassius Andrews’s brother’s body is stolen, Andrew is determined to recover it. His quest ultimately leads him to a covert investigation into death. He would have been far better off not to have searched nor seen his results.

This was about twice as long as it needed to be, which, as I recall, was also what I thought about Jakes’ Mention My Name in Atlantis. Jakes abandoned SF for the more lucrative world of historical fiction, an accomplishment that John Brunner attempted to emulate (and squandered years he could not afford in doing so). Not that Brunner’s error was Jakes’ fault.

1: Not to worry: our hero does manage to train his dim bride so she can parrot what he deems adult conversation.

2: Where did Cain get his wife?