At Least It Was Short

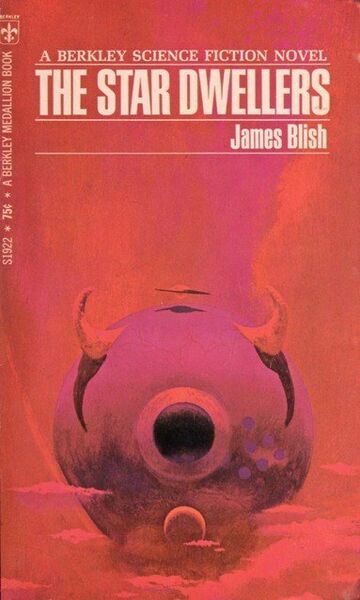

The Star Dwellers (Heart Stars, volume 1)

By James Blish

15 May, 2022

James Blish’s 1961 The Star Dwellers is the first volume in the Heart Stars Duology. The Star Dwellers is a young adult novel.

Humanity has long pondered questions like:

- Are we alone in the galaxy?

- Are amicable relations between aliens and humans possible?

- How does a novel this terrible not only get published but remain in print for twenty years (more than sixty in the UK)?

The Star Dwellers answers two of those questions.

Although he is only seventeen years old, Cadet Jack Loftus has benefitted from educational philosophies far superior to those of the 1960s, ninety years earlier. Good thing for humanity, as Jack will be playing a central role in its destiny.

Einsteinian speed-of-light limitation having proven no match for Milne and Haertal’s ingenuity, human starships soon discovered that terrestrial worlds generally produce their own native intelligent life. Some, like the long-dead Martians, turn their genius on themselves. Others, like the Galactic Civilization of which Earth is very much not a part, prevail for millions of years. Where humanity will fall remains to be seen.

The McCrary Fleet’s expedition (Lancet, Probe, and Electrode) into the Coalsack Nebularevealed that intelligence is not a planetary monopoly. The fleet encountered mysterious energy beings whom humans dubbed “Angels.” This was not entirely to the fleet’s benefit: Lancet and Probe were inadvertently destroyed by the Angels. Lancet survived to return to Earth, with an Angel inadvertently held captive within the starship’s fusion generator.

Lucifer, as the humans dub the alien, is content to dwell in a human fusion reactor, where it makes itself at home. Lucifer’s inherent mastery of fusion processes makes the reactor far more efficient. The possibility exists, therefore, that the tremendous expense of space travel could pay for itself in a golden age of high-efficiency fusion power. That depends on whether friendly relations are possible between humans and Angels, and if it is prudent to entrust humanity’s energy production to heretofore unknown aliens.

Pausing only for a lengthy diatribe about the shortcomings of the American educational system in the 1960s, the stalwart Dr. Langer assembles a follow-up expedition. It will consist of just one man and two boys: Langer, his faithful cadet Sandbag Stevens, and protagonist Jack Loftus (borrowed from Secretary for Space Hart). Fending off the determined efforts of plucky girl reporter Sylvia McCrary to attach herself to the mission, the three race in Langer’s Ariadne at ultra-high speed to the Coalsack.

Venturing into the dark nebula with a fusion-powered starship invites the fates of Lancet and Probe. Langer has a solution as bold as it will be unsuccessful. Langer and Sandbag sail into the heart of the nebula using a light-sail, leaving Jack behind in Ariadne.

As fate has it, Ariadne’s fusion generator lures a curious Angel to investigate. Although he is merely a boy, it falls to Jack to establish friendly relations and negotiate a treaty between immortal aliens and all too mortal humans. Failure won’t merely doom Langer and Sandbag (whose sail ship is woefully unprepared for conditions in the Coalsack). It may well reveal humans as one of the galaxy’s also-rans.

~oOo~

Blish considerately begins the novel with a short science lecture about the nature of life, in the course of which he demonstrates a mistaken (but not uncommon) belief that life is not subject to the laws of thermodynamics. This misapprehension turns up a lot in creationist circles; given that Blish was already a self-described fascist1, one has to wonder to what heights of crankery2 he would have ascended had he not perished of cancer in 1975.

SF worlds often being quite different from ours, SF authors face the need to somehow convey these differences to readers in unobtrusive ways. Blish for some reason decided the best method was to for the adults to demand Jack read from what amounts to a term paper while shouting at him to skip the boring bits everyone knows. This seems to be part and parcel of the 21st century’s educational system, based on lofty standards, celibacy, and an endless stream of derisive verbal abuse aimed at students.

Langer’s loathing of the mid-20th century (to him as 1930 is to us) is not limited to education. There’s also the matter of its popular music, which as we know was just noise. Salacious noise.

Of course, music for dancing has to be different from concert music in kind. But in those days it was vastly inferior in quality, too; in fact most of it was vile. And it was vile mainly because it was aimed at corrupting youngsters, and then after that job had been done, the corrupted tastes were allowed to govern public taste in music as a whole. We’re very lucky that we ever got off that particular chute-the-chutes. It would never have unwound itself if it hadn’t been for the revolution in education, which among other things involved the realization that music — and poetry — are primarily arts for adults, and for exceptional adults at that.

Of course, given that Langer’s plan to contact the Angels goes disastrously wrong, perhaps his reliability as an authority is open to question.

Speaking of Langer’s failings: Sylvia McCrary is at every turn determined, brave, ingenious, and resourceful, and it’s pretty clear she would have been an asset to the expedition.

What with the infodumping and diatribes, it takes the plot some time to get going. Just as well, since the situation proves very nearly self-resolving, Angels being a very reasonable lot. The plot is resolved almost immediately, save for some business at the end involving Jack having inadvertently led an armada of Angels to Earth, and whether the treaty Jack negotiated is sufficiently useful to overlook that not only did he wildly overstep his authority negotiating it, as a minor his agreement cannot be binding.

Blish was, of course, not merely a respected science fiction author. Under the pen-name William Atheling, Jr. he was with Damon Knight one of the Eisenhower-era science fiction’s few active literary critics. Blish was utterly scathing when SF failed to meet his exacting standards3. It’s rather a puzzler, therefore, how Blish managed to write and publish The Star Dwellers without ever noticing what a comprehensive stinker it is. His sideline as critic does make this book more than fair game, however4.

The Star Dwellers appears to be mercifully out of print5 except in the United Kingdom’s Amazon UK, because apparently having Boris Johnson as Prime Minister isn’t punishment enough. Well, they’ve only themselves to blame.

1: For confirmation see Blish introduction to his fascist utopia A Torrent of Faces.

2: One always has to wonder how many relativity skeptics are motivated by antisemitism. Well, not if one ever hung out on Usenet’s science-related newgroups: the answer is lots. Although in Blish’s case, the motivation for rejecting relativity was likely because his plot would not work otherwise.

3: As far as I am aware, Blish never managed to torpedo anyone’s career with his criticism, whereas Knight’s scathing commentary on van Vogt’s incoherent adventure SF did that author no favours.

4: Why now? A recent Twitter thread about Blish (and the fact that as Atheling, he reviewed his own books) reminded me of it. In the spirit of those resisting student loan forgiveness, if I had to suffer through those memories, you should too.

5: Whereas Blish’s collections of critical essays are available from Smashwords.