And What Have You Got At The End Of The Day?

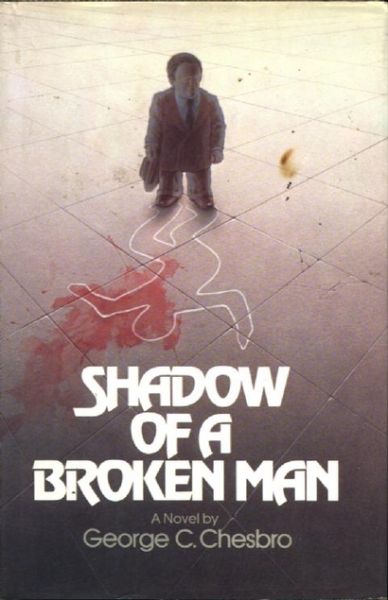

Shadow of a Broken Man (Mongo, volume 1)

By George C. Chesbro

14 Jan, 2018

1977’s Shadow of a Broken Man is the first volume in George C. Chesbro’s long-running Mongo series. The Mongo series lives in the intersection of mundane detective fiction and outright science fiction. Or at least I think it does.

Former circus tumbler turned black belt martial artist turned academic, criminology professor Dr. Robert “Mongo the Magnificent” Fredrickson has a minor side-line as a private detective. His cases are often peculiar, as if people with normal cases don’t seek out New York’s only dwarf detective. Lookism, I suppose.

His new case seems pretty straightforward: find out how a dead man managed to design a new building.

Architect Victor Rafferty was an architectural superstar, a master at reconciling aesthetics with practicality. Rafferty is not just dead but very sincerely dead; he fell into an open smelting furnace in front of eyewitnesses. Burnt up entirely, he has no business designing new structures.

Mike Foster married Rafferty’s widow Elizabeth. Elizabeth is convinced that the Nately Museum, credited to one Richard Patern, is Rafferty’s work. Concerned for his wife’s well-being, Mike hires Dr. Fredrickson to see what, if any, connection there is between Patern and Rafferty.

The most obvious explanation is that Rafferty faked his own death and became Patern. Patern is definitely not Rafferty. Wrong age, wrong appearance, a well-documented history, and (once Dr. Fredrickson manages to interview him) a credible, mundane explanation for the similarity between Rafferty’s work and his own: Patern studied Rafferty’s designs closely. There’s just one odd detail: the seed for Patern’s design was a sketch he found discarded or lost after a UN seminar. No way to know who created that sketch. But it could not have been Rafferty, because Rafferty was long dead by that time.

The next logical step is to start asking questions at the UN. It’s at this point that Dr. Fredrickson’s investigation hits a snag. Asking questions about the late Mr. Rafferty gets the attention of a wide assortment of scary men from a number of intelligence agencies. Rafferty, it seems, had a unique gift known to spies, but not to the world at large. The spies of the world are determined to have Rafferty either working for them or dead. Suspicious that Dr. Fredrickson knows more than he admits, suspicious that Rafferty’s death was might somehow have been faked, the aforementioned scary men would like Dr. Fredrickson to share with them everything he knows about Rafferty.

And if he does not want to cooperate? Well, there are ways of making an unwilling man talk.

~oOo~

Although it sometimes causes social awkwardness — ignoring the elephant in the room by refusing to acknowledge that Dr. Fredrickson is a dwarf — dwarfism is sometimes quite useful. The professor’s opponents tend to dismiss him as too small to be a threat, not realizing that he is a super-fit acrobat skilled in hand-to-hand combat. He may only come up to his foes’ chins, but he can come up to those chins with considerable force.

Although this narrative is set during the Cold War, the conflict that drives the plot isn’t as simple as East versus West. Every intelligence agency wants to control Rafferty’s superhuman abilities. The Americans, British, and French may be nominal allies in the Cold War, but they are rivals in the hunt for Rafferty. For all I know, that may well be true for the several intelligence agencies within nations: the CIA may want to get their paws on Rafferty and shut out the FBI or DIA.

That said, the Russian field agent is a violent, sadistic brute; if the plot is painted in shades of grey, his shade is very very dark. The French, the British or the Americans may be willing to kill Dr. Fredrickson to get what they want, but Kaznakov will take time to ensure the professor’s demise is as painful as possible.

Like other authors I could name, Chesbro, the author of this diversion, had an idiosyncratic definition of science fiction. He didn’t think this novel qualified:

“Shadow may be where I started to build a reputation for pushing the envelope of detective fiction, crossing genres by mixing mystery and science fiction. In fact, nothing could have been further from my mind. Sci fi deals in alternate worlds/realities, and Mongo is very much a man of our time and reality. I just wanted to tell a good story, and it occurred to me that it would be great fun to explore the implications of having na npghny gryrcngu — but only one — in our world. I concluded that it would be dangerous and potentially disastrous for all concerned, and in the novel I attempt to show why.”

I would regard questions like “what are the social implications of an extraordinary event?”1 as very much SFnal. I thought the Mongo series SFnal enough that I picked up most of it over the years. As it went on, the plots grew increasingly weird and bizarre. What may have seemed a mundane world in the first novel turned out to be well stocked with paranormal and occult secrets. Secrets waiting for the right dwarf detective to unravel them. Dr. Robert “Mongo the Magnificent” Fredrickson was the right dwarf detective.

Shadow of a Broken Man is available here (Amazon) and here (Chapters-Indigo).

1: Speaking of implications, while correlation is not causation, Rafferty didn’t develop his powers until he had suffered a serious head injury, which was followed by cutting edge neurosurgery. What he could do was documented, as was the accident, the nature of his injuries, and the medical procedure. The author may know that this was a unique event, but would the intelligence agencies have known that? If I were to enter the world of the novel and do a little sleuthing, I think I would find that all too many unfortunate volunteers and voluntolds were being subjected to head injuries followed by futile treatment, in hopes of creating another Rafferty. For the good of the state (or the agency) you know.